From the islands of Indonesia to the northern highlands of Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar, indigo has deep connections to identity and community well-being.1 In a region with varied histories, languages, beliefs, and artistic expressions, following the thread of indigo and its continued relevance in Southeast Asia requires tracing the history of the peoples who have long called the region home.

Most studies of Southeast Asia split the area into subregions based on shared geography and history: island and peninsular Southeast Asia and mainland Southeast Asia (Figure 2). Cultural, linguistic, artistic, and colonial histories are typically divided along these lines, as is the study of textiles. Throughout the islands and the mainland, wealthy and powerful empires developed in the first millennium CE in the plains of the major rivers and along the ports of trade, connecting India and Southeast Asia. As kingdoms developed, trade and commerce were essential. Spices and local products were exported from Southeast Asia, and textiles—often dominated by the color blue—were brought from India for the larger population’s consumption. The long-standing influence of Indian textiles is still manifest in the region’s textiles, most notably in the islands of Indonesia.

One mystery of indigo relates to its establishment and development in Southeast Asia: Was the plant growing there before Indian textiles came to dominate trade? And if so, was it already used for producing dye? Or was it introduced to local textile artisans and local gardens through trade with the Indian subcontinent? Either possibility is plausible. The monsoonal climate of Southeast Asia bears many similarities to South Asia, and the regions share many flora and fauna. With no indication of indigo (or any other textile components) in the archaeological record of Southeast Asia, the origins of indigo in the region are unclear. Yet the eventual proliferation of indigo in the textiles and beliefs of peoples across Southeast Asia is proof of the long-standing importance of the plant and its dye.

The environment and climate of much of Southeast Asia is conducive for indigo, but the ability to yield a potent dye and color from the plant depends on the attention given to cultivating it. Indigo grows wild in many places, but producing a dye with strong, consistent color requires close attention, from planting through dye creation.2 From the twentieth century onward, indigo plants have been established, cared for, and harvested by individuals within households or small communities. However, in centuries past, indigo was an important crop for colonial governments, from Vietnam to Java.

Although indigo textiles, cultures, histories, and contexts vary by region and locality, key beliefs and contexts for indigo dyeing and indigo cloth are shared. For instance, indigo is almost exclusively situated in the realm of women. Their knowledge and specialization informs a delicate, precise, and seemingly magical process. They harvest indigo, create the dyestuff, ensure its potency, and dye threads and textiles repeatedly until the desired color is achieved.

The creation of such textiles has long been considered vital to group identity. Connection to the group’s ancestors, and even to the community’s livelihood, depends on the successful dyeing and production of cloth (Figure 3). In an important study, Robyn Maxwell details how indigo is treated by communities in island Southeast Asia, revealing the precarious nature of indigo production.3 Indigo dyeing requires a detailed understanding of the many steps necessary for successful dye extraction, precision, and a controlled environment. Stories and restrictions are rife, with narratives that establish who can access the indigo and who can share the secrets of the dyeing process. Maxwell recounts a legend from the Indonesian island of Sawu of two sisters who were on the verge of learning their mother’s secret recipe for creating indigo blue. One of the sisters tried to steal the indigo in the middle of the night in order to keep the secret from her sister. In her ignorance, she poured out the fluid, essential for indigo’s success, and ran away with the pot, holding only the waste product. As a result, the descendants of the indigo-stealing sister have never achieved the indigo-dyeing prowess of the other sister’s heirs. Following protocols for creating and using indigo dyes ensures that the finicky dye will be effective and achieve its desired results. This in turn helps communities sustain their livelihoods, even in the face of change.

Indigo in Island Southeast Asia

Indigo and its continued widespread use throughout Indonesia are deeply connected to the textiles created throughout the islands and the influx of textiles traded by India. Most likely introduced as predominant textile colors through the Indian textile trade, blue (indigo) and red (chay or madder) textiles were preferred by Indonesian consumers, as early as the ninth century.4 Textile trade between India and the islands of Southeast Asia proliferated even after Europeans pushed in to dominate the market, with a decline in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a result of industrialization.

Imported textiles, often dominated by indigo blue, were highly valued as articles of clothing and ritual objects. Local Indonesian weavers and dyers incorporated powerful colors and motifs into their own work, which was used in much the same way as the Indian imports.5

The quality and quantity of textiles integral to regional courts; the use of textiles as gifts to visiting dignitaries and allies; and the role of textiles in honoring healing forces and in ceremonial events meant that having the right textiles ensured the health of a community. Even today, indigo is often integral to the beauty and potency of these textiles. Thus, understanding how to cultivate the plant and maintain a healthy vat of indigo continues to be central to the success of some communities.

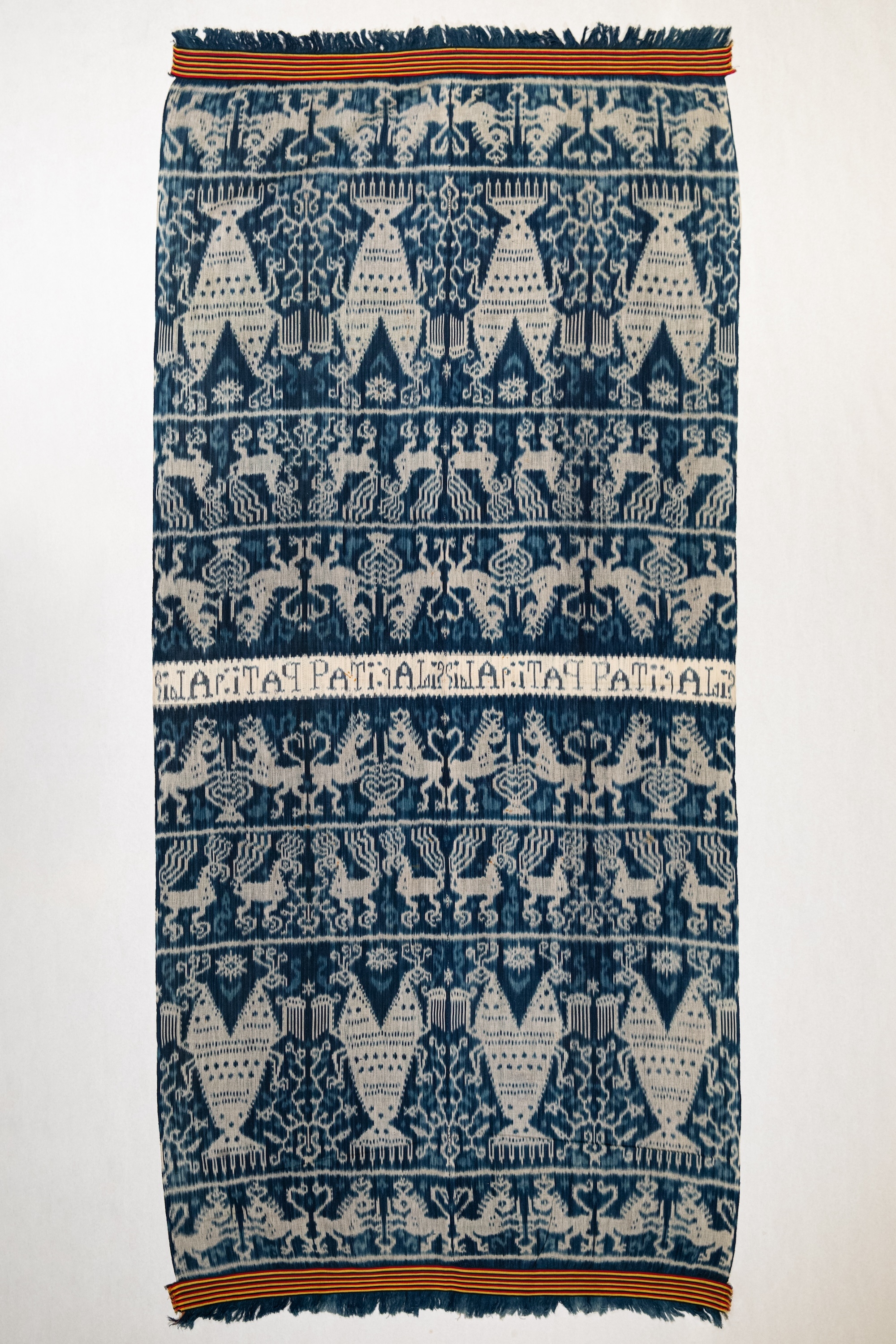

Across the islands of Indonesia, intricate textiles are essential components of the visual world. Indonesian dyers and weavers create technically complex and symbolically rich textiles sought out by collectors and consumers near and far (Figure 4). As mentioned above, the growing, harvesting, processing, and dyeing with indigo plants has been the purview of women. These women guard their knowledge and their indigo dye pots from malevolent forces and help to maintain connections to their ancestors. Their labor includes not only overseeing the process of making vats but also dipping textiles in the dye pot many times to yield the deep, dark blues that are popular throughout the region.

In one example, on the island of Flores, women grow indigo in small quantities in fields or household gardens. They tend to these plants using small ceramic pots as oxygen-reduced vats. Yarns are dyed in these vats, and many dips are required to achieve a deep blue-black color.6 In Manggarai, the northeast area of Flores, the dyeing of threads with indigo is a precarious time during which all actions and behavior need to be carefully moderated. The treatment of the dye pots and the use of language is tightly controlled, likely a reflection on the precarious nature of dyeing with indigo and the power of indigo cloth in local communities.7

Another Indonesian island well known for its bold and figurative indigo-dyed warp ikat textiles is Sumba, where scholar Janet Hoskins studied the role of indigo in East Sumba life and textiles. There, the older women who guard the secrets of creating potent indigo dye vats are part of a lineage of women with this specialized knowledge. Indigo dye remains in the purview of older women because the substance is believed to be “dangerous to all men and to women of reproductive age.”8 These women hold many secrets about poisons and fertility and are regarded as potentially dangerous, with intense power as a result of their specialized knowledge. The women carry out the indigo dyeing in a dye shack in a remote location, to ensure the safety of all. They make offerings to their ancestress, who is from Sawu, a neighboring island mentioned in the introduction to this essay. To be an older woman who oversees the processing of indigo is to gain status in a community. The blue color and the motifs created in the dyed textiles have great potency. They help communities stay connected to the past, remain viable in the present, and find ways to survive amid unprecedented change.9 Although indigo has maintained its relevance in areas that continue to value handwoven and locally dyed cloth, external markets help to support these long-standing practices.

Indigo Cloth in Ethnic Minority Dress of Mainland Southeast Asia

Ethnic minorities living in the highlands of northern Southeast Asia populate the landscape from Myanmar to Vietnam to the borderlands of China. They are known for their brightly colored embroideries and deep-blue hemp and cotton fabrics (Figure 5). Each of these groups, including the Hmong, Karen, Chin, Akha, and Yao, migrated to the region over many centuries, drawn to its relative political independence and fertile lands. For these ethnic minority groups, textiles are visible markers of group identity. Their indigo-rich woven, embroidered, and appliquéd surfaces serve as protection from malevolent spirits and connect the wearers to their ancestors and to unwritten histories of migration and struggle.10

Indigo is central to many of these groups’ survival and identity, ensuring its continued use over time. Both practical and ceremonial in use, indigo dye functions as an insect repellant, and it is a vital component of the durable clothing necessary for daily and ritual life in a mountain environment. Indeed, its effectiveness for cotton and hemp textiles continues long after a textile’s initial use. Once indigo clothing becomes faded, especially work clothes worn for daily activities, the garment is often redyed in an indigo vat.

Many of the minority groups in the mountainous regions of Southeast Asia also have a strong presence in southwestern China, where they largely fall under the umbrella term “Miao.”11 Because these groups’ political environments are often volatile, and because they face rapid change, the survival of textile production and especially the continued use of indigo is not guaranteed. Many communities have already ceased to produce their own textiles or to manufacture the ground cloths that support other groups’ colorful and detailed embroidered and appliquéd textiles. In a volatile region with little wealth, often the only way a community can maintain its practices is with assistance from the outside.

Not all the rich indigo textile traditions of northern Southeast Asia have been studied in depth, creating a stark contrast between outsiders’ knowledge of this region and the attention given to the textile traditions of Indonesia. Documentation from British colonial and missionary accounts from the early twentieth century in what is now Myanmar give few specific details about the textiles of ethnic minority communities. They describe men’s and women’s textiles as being white, blue, or black (with black most likely being a deep indigo before affordable chemical dyes became widely available), but offer little specificity in their descriptions.12

The Yao Mun people of northwest Laos provide a striking example of indigo use as integral to group identity. Their commonly accepted name of “Lanten,” given to them by outsiders, identifies them as people who wear indigo cloth. Only a few communities continue to live in traditional villages; those who do wear deep-blue indigo clothing. Their indigo-dyeing process involves boiling cloth in indigo for at least twenty days. Adhering to the time-consuming practices of harvesting and processing both the cotton and the indigo for local cloth remains essential for group cohesion and local pride.13 Laos-based organizations, notably the Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre in Luang Prabang, have been integral to the documentation, support, and survival of Yao Mun indigo cotton cloth in Laos.14

The Chin people of what is now western Myanmar once created some of the most exquisitely detailed textiles in the region.15 Their densely woven cotton and hemp textiles feature detailed geometric motifs set against a dark blue/black, white, or red ground. Since there is no written language and few surviving textiles, understanding Chin textile production before the twentieth century proves challenging. Indigo was once a primary component of Chin textiles, used as a dye on both cotton and hemp.16 Weavers combined indigo yarns with fibers dyed red with lac to create vibrant, dense textiles, used for clothing, household items, and more.17 Communities grew indigo in household gardens, but today the importing of chemical dyes and mass-produced yarns has largely replaced local indigo production.

Because of the incredible skill required to create the fine details of each Chin textile, these objects have been widely collected globally. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Chin artifacts have survived in museums and private collections, preserving the textiles for the wider public to learn about, while leaving these communities bereft of their heirloom objects. In recent years, Myanmar nationals have worked to save Chin textiles and encourage communities to restore such traditional practices as indigo dyeing and intricate weaving.18

Hmong communities developed unique ways of embellishing and dyeing their textiles. These groups—now scattered across China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand—once held their cultural histories and narratives in detailed embroidered, appliquéd, and batik textiles, made for use as ceremonial dress and as objects for special occasions (Figure 6). Their textiles revealed household wealth and identity for migrating peoples whose seminomadic lifestyles were impacted by dominant groups living in the valleys below. One of the most important materials uniting various Hmong groups’ style of dress is indigo. Grown, harvested, and processed by women, who oversee all aspects of textile production and embellishment, indigo is especially prized after numerous dips in the vat achieve a blue that is so rich as to be nearly black.

Today, indigo is heralded in Hmong communities in Vietnam as an important natural dye essential to sought-after textiles from Sa Pa and surrounding regions.19 This “natural dye” role of indigo is also touted as being part of the sustainable fashion industry in Vietnam. Makers and advertisers praise the ethnic minority textiles of the north as providing critical connections to the past and embodying sustainability. This focus on “natural dyes” has taken root in Vietnam and across Southeast Asia, ensuring that groups whose textiles and identities rely on the plant and its output will be central to future conversations about textiles. Such actions and perceptions are important, as fears about the replacement of indigo with synthetic dyes are long-standing.

Conclusion

The importance of indigo textiles for the diverse peoples of Southeast Asia cannot be overstated. From sustaining group cohesion in the face of change and outside pressures to honoring ancestors and maintaining community health, indigo continues to be integral to textiles and societies across the region. While anthropologists and textile scholars have created a wealth of scholarship about the role of indigo in Indonesian communities, more studies and insights are needed in the mountainous north of mainland Southeast Asia, where indigo textiles are not receiving the in-depth attention that is needed. The rampant changes of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have required indigo dyers and textile makers to either find new markets and outlets for their products, or cease to produce the deep and lustrous blues that have defined them for generations. Further documentation of their production methods, their histories and stories, and the reasons for their continuation is needed. We likewise need to support these knowledgeable, hardworking, and insightful women whose textiles fill collections around the world.

Notes

-

Numerous studies explore the rich meanings, uses, histories, and beliefs about indigo in Southeast Asia. Scholarship on Indian trade textiles also continues to expand, with many books, essays, and symposia on the enormity of textile markets and their inevitable influence on textile production in both South and Southeast Asia. See Mattiebelle Gittinger, Master Dyers to the World: Technique and Trade in Early Indian Dyed Cotton Textiles (Washington, D.C.: Textile Museum, 1982); John Guy, Woven Cargoes: Indian Textiles in the East (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1998); Ruth Barnes, ed., Textiles in Indian Ocean Societies, Routledge Indian Ocean Series (London and New York: Routledge Curzon, 2005); and Sarah Fee, ed., Cloth That Changed the World: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2020). ↩︎

-

Jenny Balfour-Paul, “Indigo in South and South-East Asia,” Textile History 30, no. 1 (1999): 98–112 at 103. ↩︎

-

Robyn Maxwell, Textiles of Southeast Asia: Tradition, Trade, and Transformation, rev. ed. (Hong Kong: Periplus Editions, 2003), 144. ↩︎

-

Balfour-Paul, “Indigo in South and South-East Asia,” 99. ↩︎

-

Ruth Barnes, “Indian Textiles for the Lands below the Winds,” in Cloth That Changed the World, ed. Fee, 73–75. ↩︎

-

Roy W. Hamilton, ed., Gift of the Cotton Maiden: Textiles of Flores and the Solor Islands (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, University of California, Los Angeles, 1994), 62. ↩︎

-

Maribeth Erb, “The Curse of the Cooked People: Weaving in Northeastern Manggarai,” in Gift of the Cotton Maiden, ed. Hamilton, 206. ↩︎

-

Janet Hoskins, “In the Realm of the Indigo Queen: Dyeing, Exchange Magic, and the Elusive Tourist Dollar on Sumba,” in What’s the Use of Art? Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context, ed. Jan Mrázek and Morgan Pitelka (Honolulu: University of Hawai῾i Press, 2008), 104. ↩︎

-

Janet Hoskins, “Why Do Ladies Sing the Blues? Indigo Dyeing, Cloth Production, and Gender Symbolism in Kodi,” in Cloth and Human Experience, ed. Annette B. Weiner and Jane Schneider (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 1989), 158–62. ↩︎

-

Writing with Thread: Traditional Textiles of Southwest Chinese Minorities; A Special Exhibition from the Collection of Huang Ying Feng and the Evergrand Art Museum in Taoyuan, Taiwan (Honolulu: University of Hawai῾i Art Gallery, 2009). ↩︎

-

The label “Miao” is applied to ethnic minorities in the southwestern provinces (mostly centered on Guizhou Province and Guangxi Autonomous Region. Although many people mistake the “Miao” label to mean “Hmong,” this is inaccurate. Miao can mean any number of ethnic minorities with similar languages and characteristics but distinct local histories and identities. See Jacques Lemoine, “What Is the Actual Number of the (H)mong in the World?” Hmong Studies Journal 6 (2005): 1–8. ↩︎

-

See Michael C. Howard, Textiles of the Hill Tribes of Burma (Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 1999), 33–36. ↩︎

-

Jess G. Pourret, The Yao: The Mien and Mun Yao in China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand (Bangkok: River Books, 2002), 187. ↩︎

-

Tara Gujadhur, “Lanten: The Indigo Yao of Laos,” August 2018, Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre website, Luang Prabang, Laos, [https://www.taeclaos.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/PDF-[Lanten_TAEC_LuangPrabang_Laos.pdf](https://www.taeclaos.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/PDF-Lanten_TAEC_LuangPrabang_Laos.pdf)] ↩︎

-

The Chin people’s textile-production techniques and cultural meanings were largely ignored by outsiders and anthropologists until the early twenty-first century. See David W. Fraser and Barbara G. Fraser, Mantles of Merit: Chin Textiles from Myanmar, India, and Bangladesh (Bangkok: River Books, 2005), 145. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 273. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 39. ↩︎

-

See Marilyn Murphy, “Sustainable Hand Weaving Makes Its Way out of Myanmar,” ClothRoads website, [https://www.clothroads.com/sustainable-hand-weaving-makes-its-way-out-of-myanmar;]{.underline} and “Not for Sale: Chin Heritage Textiles Collection Exhibited in Chiang Mai,” The Irrawaddy, August 31, 2023, https://www.irrawaddy.com/culture/not-for-sale-chin-heritage-textiles-collection-exhibited-in-chiang-mai.html[https://www.irrawaddy.com/culture/not-for-sale-chin-heritage-textiles-collection-exhibited-in-chiang-mai.html](https://www.irrawaddy.com/culture/not-for-sale-chin-heritage-textiles-collection-exhibited-in-chiang-mai.html). ↩︎

-

Chi Yen Ha, “Fashioning Indigeneity: Representations of Ethnic Minority Textiles in Vietnam’s Creative Economy” (master’s thesis, University of California, Riverside, 2022), 34–35. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Balfour-Paul 1999

- Balfour-Paul, Jenny. “Indigo in South and South-East Asia.“ Textile History 30, no. 1 (1999): 98-112.

- Barnes 2005

- Barnes, Ruth, ed. Textiles in Indian Ocean Societies. Routledge Indian Ocean Series. London and New York: Routledge Curzon, 2005.

- Barnes 2020

- Barnes, Ruth. “Indian Textiles for the Lands Below the Winds.“ In Cloth That Changed the World: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz, edited by Sarah Fee, 73-75. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2020.

- Erb 1994

- Erb, Maribeth, “The Curse of the Cooked People: Weaving in Northeastern Manggarai.“ In Gift of the Cotton Maiden: Textiles of Flores and the Solor Islands, edited by Roy W. Hamilton, 62. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, University of California, Los Angeles, 1994.

- Fee 2020

- Fee, Sarah, ed. Cloth That Changed the World: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. 2020.

- Fraser and Fraser 2005

- Fraser, David W., and Barbara G. Fraser, Mantles of Merit: Chin Textiles from Myanmar, India, and Bangladesh. Bangkok: River Books, 2005.

- Gittinger 1982

- Gittinger, Mattiebelle. Master Dyers to the World: Technique and Trade in Early Indian Dyed Cotton Textiles. Washington, D.C.: Textile Museum, 1982.

- Gujadhur 2018

- Gujadhur, Tara. “Lanten: The Indigo Yao of Laos.“ August 2018. Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre website, Luang Prabang, Laos, https://www.taeclaos.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/PDF-Lanten_TAEC_LuangPrabang_Laos.pdf.

- Guy 1998

- Guy, John. Woven Cargoes: Indian Textiles in the East. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1998.

- Ha 2022

- Ha, Chi Yen. “Fashioning Indigeneity: Representations of Ethnic Minority Textiles in Vietnam’s Creative Economy.“ Master’s thesis, University of California, Riverside, 2022.

- Hamilton 1994

- Hamilton, Roy W. Gift of the Cotton Maiden: Textiles of Flores and the Solor Islands. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, University of California, Los Angeles, 1994.

- Hoskins 1989

- Hoskins, Janet. “Why Do Ladies Sing the Blues? Indigo Dyeing, Cloth Production, and Gender Symbolism in Kodi.“ In Cloth and Human Experience, edited by Annette B. Weiner and Jane Schneider, 158-62. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 1989.

- Hoskins 2008

- Hoskins, Janet. “In the Realm of the Indigo Queen: Dyeing, Exchange Magic, and the Elusive Tourist Dollar on Sumba.“ In What’s the Use of Art? Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context, edited by Jan Mrázek and Morgan Pitelka, 100-126. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008.

- Howard 1999

- Howard, Michael C. Textiles of the Hill Tribes of Burma. Bangkok: White Lotus Press, 1999.

- Lemoine 2005

- Lemoine, Jacques. “What is the Actual Number of the (H)mong in the World?“ Hmong Studies Journal 6 (2005): 1-8.

- Maxwell 2003

- Maxwell, Robyn. Textiles of Southeast Asia: Tradition, Trade, and Transformation. Rev. ed. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions, 2003.

- Murphy 2015

- Murphy, Marilyn. “Sustainable Hand Weaving Makes Its Way out of Myanmar.“ ClothRoads website, May 7, 2015. https://www.clothroads.com/sustainable-hand-weaving-makes-its-way-out-of-myanmar.

- Murphy 2023

- Murphy, Marilyn. “Not for Sale: Chin Heritage Textiles Collection Exhibited in Chiang Mai.“ The Irrawaddy, August 31, 2023, https://www.irrawaddy.com/culture/not-for-sale-chin-heritage-textiles-collection-exhibited-in-chiang-mai.html.

- Pourret 2002

- Pourret, Jess G. The Yao: The Mien and Mun Yao in China, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand. Bangkok: River Books, 2002.