This essay begins with the historical backdrop for indigo in the former French colony of Louisiana, focusing on the harmful effects of the indigo trade on Indigenous and enslaved people. It then turns to the science and art programs organized by Atelier de la Nature, an environmental education center in Arnaudville, Louisiana. A study of the use of indigo in nineteenth-century medicine—in particular, for staining tissue for study under a microscope—has documented an early diagnostic tool that had never been photographed in color before. A community effort to plant native indigo and other Louisiana species has led to the restoration of Cajun Prairie, the most endangered habitat in North America. Finally, a partnership with members of the Coco Tribe of Canneci Tinné has helped to reclaim Indigenous knowledge of using native indigo species to color ceremonial objects. Altogether, these collaborations between art and science at Atelier de la Nature have sought to preserve not only an important ecosystem but also vital Indigenous knowledge about native indigo.

Native indigo-producing species of the genus Baptisia once flourished in many regions of North America, including Louisiana. It is apparent that Indigenous groups in the Americas used indigo prior to European colonization, but the historical record is limited.1 Though Baptisia is not suited for the production of indigo on a commercial scale, the presence of these naturally growing plants indicated that the land could be used for cultivation of Indigofera species, imported from the tropics.2 Colonial records show that endemic indigo-producing plants were also used by Indigenous populations for medicine.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Europeans competed to control the indigo trade and, in doing so, propagated human oppression and environmental degradation. This exploitative system of indigo production thrived, especially in the American colonies. From the perspective of Indigenous and African populations, indigo plantations in the Americas were spaces of oppression and bodily harm. People were purposefully displaced in violent and disruptive ways that eroded ecological traditions and connections as they rebuilt their lives in new environments. In turn, Indigenous knowledge was used to establish the cultivation and dye-making process in the colonies. Records indicate that Indigenous peoples were specifically selected for enslavement on indigo plantations, which indicates that they likely had knowledge of indigo.3

For planters, indigo was a risky business, with complicated growth requirements and processing that was often fraught with failure, which resulted in price fluctuations and a flux of trading partners.4 Worse, plantations required a large capital investment and labor. For indigo producers in America, the main competition was from Spanish plantations in Guatemala. There, Maya and other Indigenous populations were forced to share their knowledge of extracting high-quality indigo from endemic species under harsh conditions. In 1798, war between Spain and Britain sidelined the indigo trade, and not long after, a locust outbreak decimated Guatemala’s indigo prices and reputation.5 High export duties led Britain to turn to South Carolina to compete with Spain. France mostly focused on Haiti—and Louisiana.6

Louisiana indigo production likely began in the 1720s, when French Jesuit settlers brought seeds and advisors from the Caribbean.7 In this tropical climate, Indigofera was an ideal crop, and by 1724, indigo factories were being built in Louisiana to extract dye for trade.8 In 1731, the French set up land grants for indigo plantations along the Mississippi River, in what is now New Orleans.9 By the mid-1700s, Louisiana indigo was booming. By this time, South Carolina, which was colonized by the British, had become a prominent producer of indigo for export. But the region faced a series of setbacks. War and conflict hamstrung the French operations, which were further insulted by British tariffs and trade practices, allowing the South Carolina market to grow considerably.10

The transatlantic slave trade was a critical part of indigo cultivation in Louisiana. Not only did enslaved Africans labor to grow and process indigo, but West Africans in particular provided crucial knowledge about indigo cultivation and processing. By 1719, French colonists sought both seeds and enslaved persons from West Africa, particularly from Senegambia, where indigo was grown.11

Indigo cultivation and extraction were harsh, with toxic byproducts that had deadly consequences. Extraction of indigo dye caused not only discomfort and annoyance but also lung problems, skin diseases, and cancer.12 The putrid smell of fermentation attracted swarms of flies, and many enslaved persons working on indigo plantations paid with their health and their lives.13 Indigo caused poor ecosystem health, too. The refuse from indigo processing was dumped and drained into creeks and streams, creating polluted water that was unfit to drink, or even to wash or bathe in. Indigo cultivation also exhausted the soil.14

But indigo was more than a commercial crop. The plants and the dye did, and still do, hold a special place in many African cultures. They highlight a bittersweet link—connecting descendants to their homeland but reminding them that their forebears were subject to a life of violence, inhumanity, and oppression.15

Indigo flourished as the major cash crop in the South until synthetic indigo was discovered in 1865 through a cheap and quick process. In turn, Indigenous knowledge of indigo cultivation and production was supplanted by commercial indigo production. Indigo was replaced by more lucrative crops like sugarcane and cotton.16 Unlike the crops that took its place, indigo’s beauty speaks to why it was valued as a commodity. It did not have the same practical uses as other cash crops like rice, cotton, or even sugar. As such, many artists and musicians have expressed this.17

As mentioned above, the invention of synthetic indigo in 1865 dramatically changed the textile industry, as chemistry was used to maximize color quality and yield. Through synthetic processes, hundreds of shades of blue could be produced. But several decades prior to that, the chemistry of indigo was already playing an important role in advancing biomedical science. Indigo was used to stain—that is, to color otherwise clear cells to better diagnose and treat diseases.

The first usable microscope was invented by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. By the mid-1700s, indigo was sulfonated (treated with sulfuric acid) to form an indigo dye now referred to as indigo carmine, a type of modified natural indigo still used today. Indigo carmine streamlined the dyeing process.

As the textile industry gained understanding of synthetic chemistry, scientists used indigo and this textile-dyeing technology to stain cells and tissues from diverse organisms. Today, microscope preparations can be stained with dozens of different dyes and stains that enable us to see features in cells and detect disease and dysfunction. But when the microscope was first invented, there were few options beyond the standard mineral pigments used in paints and fabric dyes. Indigo was among the handful of stains used to visualize cells.

Indigo’s popularity and availability made it an obvious choice as a cellular stain in early microscopy studies. Histology is a branch of the morphological sciences that studies the microscopic structure and function of cells and tissues. As such, histotechnology employs synthetic and natural dyes to highlight normal and pathological tissue structures in clinical and research laboratories.

One of the first studies to use indigo as a cellular stain was conducted in 1838 by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg, who highlighted the internal organs of various microorganisms found in water. Among the few reports that detailed early stains in tissues, L. Jullien used a mixture of indigo carmine and saturated picric acid-colored collagen, creating a brilliant blue with varied greens in the background.18 Jullien’s stain was the first differential stain for connective tissue, which saw modifications over time before ceding to the cheaper, more consistent Van Gieson’s stain, which is the dominant stain used for connective tissue today.19

Indigo is still used to stain genetic evidence from crimes, measure kidney filtration and excretion, and locate and identify lesions in the bladder and colon. However, there is no photographic record of historical indigo stains for microscopy. Scientists in the 1800s described indigo-based tissue stains as being beautiful and having excellent diagnostic value, but since indigo went out of production around the same time, its microscopic beauty was lost before the invention of color photography. Despite the enduring use of indigo in medical science, the original indigo stain results were lost, their hues and diagnostic value a mystery.

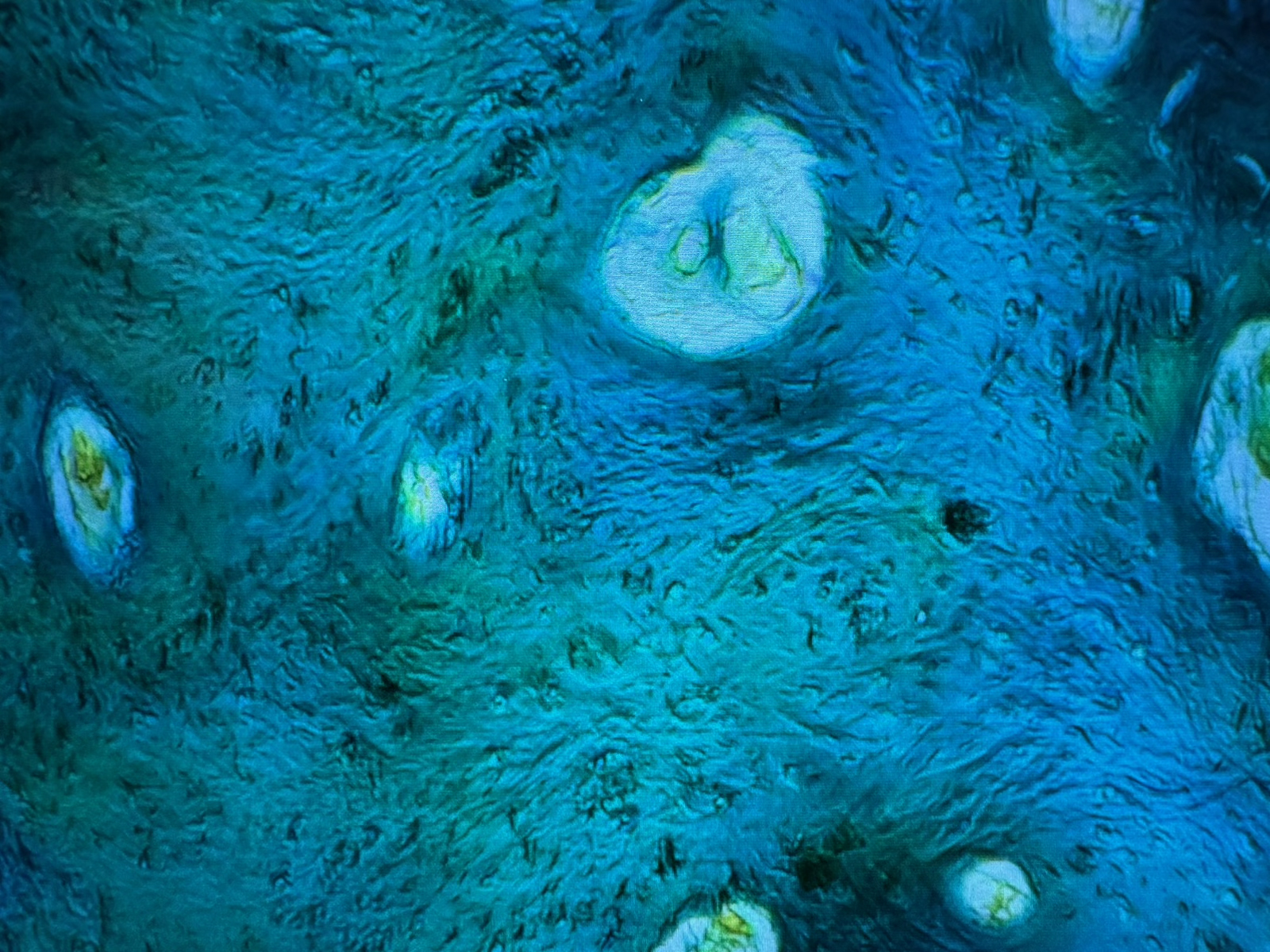

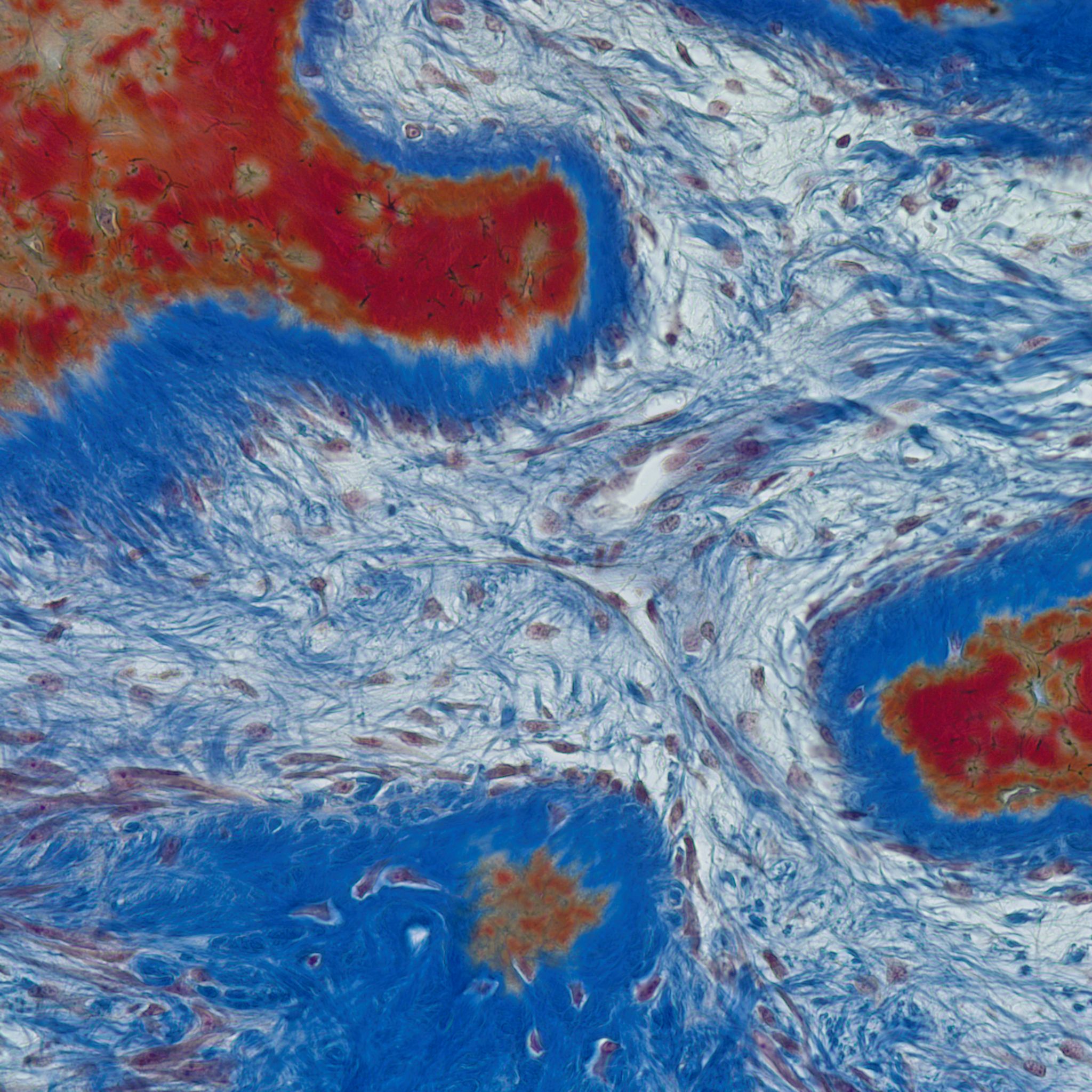

In the lab, we replicated traditional indigo-extraction techniques under controlled conditions. Pigment yields were used to make and use stains modified from the works of Jullien using modern microscopy, chemistry, and artistry. A simple recipe of indigo carmine in saturated picric acid (picroindigocarmine, or PIC) was used to test methods for staining several biological samples. We examined the vibrance and differential staining characteristics to produce test images (Figure 1A).

Early indigo stains were conducted on microscope slides we produced from intestine, liver, lung, brain, heart, and bone samples from a number of tissue types, with varying results. Test tissues revealed considerable vibrance and enhanced contrast in more heterogenous tissue samples that had multiple tissue types on a single slide. Slides with more variation in tissue type likewise showed the greatest range of coloration. As such, the boney scales of the American alligator (called osteoderms) best showcased the beauty and value of PIC as a connective tissue stain. We saw parallels between Van Gieson’s stain and PIC and consider them to be of equal diagnostic value. In the future, we will choose the stain based on which colors we want to see—the blues and greens of PIC, or the pinks and purples of the Van Gieson method. Despite the beauty of the indigo blue stains, it is likely that Van Gieson’s stain emerged as the prevailing method in medical sciences due to its consistency, ease of use, and cost (Figure 1B).

In addition to retracing early scientific practices, addressing the region’s loss of biodiversity was a key tenet of Atelier de la Nature’s approach. In the 1800s, Louisiana had an estimated 2.6 million acres of prairie, with an estimated 600–700 species of plants and animals.20 Among these were several species of “false” indigo (Baptisia species) and potentially one “true” indigo species (Indigofera suffruticosa).21 This type of prairie ecosystem is found nowhere else in the world. Cajun Prairie once covered most of southwest Louisiana, ranging from Texas to west of the Atchafalaya Basin. It was home to bison, elk, red wolves, and other now-extirpated species. Today, fewer than 100 acres of Cajun Prairie remain intact, and it is considered an endangered habitat.

Prairie habitats have largely disappeared as a result of large-scale plantations and other practices that do not support generative agriculture. Ironically, one of the first and most profitable plantation crops was the “French” indigo species (Indigofera tinctoria), along with the native “West Indian” or “Guatemalan” indigo (I. suffruticosa),22 both of which were used to produce commercial blue dyes. Indigo as a plantation crop in Louisiana dates back to the early 1700s. By 1720, the French government supplied French settlers in Louisiana with indigo plant seeds,23 and it, along with tobacco, became one of Louisiana’s biggest revenue crops in the eighteenth century.

In the spring of 2023, at Atelier de la Nature we planted a mixture of “false” indigos and other native plant species to reestablish Cajun Prairie habitat. This was performed at a public Prairie Planting Day led by Dr. Phyllis Griffard of the Acadiana Native Plant Project (Figure 2A).24 Dr. Griffard explained the history of Cajun Prairie indigo species and worked with community members to introduce starter plants and seeds of “false” indigos and other native prairie plant species. Under the direction of artist Kelli Foret Richard, young audience members created a prairie-themed mural (Figure 2B).25

In the spring of 2024, Dr. Griffard and Matthew Herron of the New Orleans Botanical Garden performed another public prairie-planting action, this time with “false” indigo (Baptisia alba and B. sphaerocarpa) as well as the native “West Indian” or “Guatemalan” indigo (I. suffruticosa). As a group, we also aimed to stop using the term “false” in the common names of Baptisia species and use the term “wild” indigo instead, as a means of using valorizing terminology for indigenous species, as opposed to devaluing words.

In the fall of 2023, leaves from “wild” indigo species were collected from the Atelier prairie. Additionally, we gathered leaves of B. alba and B. sphaerocarpa from nearby prairies. Also in the fall of 2023, the New Orleans Botanical Garden allowed us to harvest leaves from I. suffruticosa plants; we also harvested I. tinctoria from the campus of Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. This plant material was used as a histological tissue stain, as discussed above, and for the extraction of phytochemical compounds used for fabric dye in the case of our work with the Coco Tribe of Canneci Tinné.

This group is named after Chief Coco and the documentation of the tribe, which has been in Louisiana since the 1700s. The tribe comes from Canneci (Shaw-neshi) Tinné, or Trees in a Row Standing People and Red Mud People. They are part of the Forest People of the Lipan Apache, who occupied the Red River area in Louisiana before the Louisiana Purchase, from the early 1700s to 1786. The tribe occupied St. Martin Parish (Prairie Maronne) and Lafayette Parish (Bayou Tortue) in the 1800s when Canneci captives were brought to that area and then were emancipated or ran away from their captors. They have continued their culture in the Bayou Country in spite of outside pressure of assimilation and erasure.

The color tatxe (blue) is significant for the Canneci people, signifying south, adolescence, and water. Water likewise has a special meaning for them, not only as a source of seafood but also as a means of travel by canoe. The color tatxe is used in Canneci clothing and objects to reference these meanings. But owing to the encroachment of technology and European culture, Indigenous Louisiana peoples have nearly lost their use of indigo as a source of blue.

In March 2023, Coco Tribe Nant’a (Chief) Kugr Goodbear and tribal elder Lou Ann Moses worked with natural dye experts Ellie Barker and Suzanne Chaillot Breaux to relearn the indigo-dyeing process, which they believe the tribe had historically used but then lost over time. Nant’a Goodbear dyed heirloom Acadiana-grown brown cotton thread for use in a ceremonial turtle rattle. Ms. Moses worked to dye a ceremonial dress, which will be used for a traditional dance (Figures 3A, B).

Many of the findings mentioned above were presented at a two-day symposium, “Le Bleu Perdu: The Lost Art, Science and Culture of Indigo,” held March 9–10, 2024, at Atelier de la Nature and produced by Atelier co-founders Aurore and Brandon Ballengée. The talks, readings, and hands-on activities included “Tangled Up in Blue: The Complex Socio-Cultural Dimensions of Indigo” by Dr. Sarah Franzen; “Creating the Blue Hue in Colonial Louisiana” by Dr. C. Ray Brassieur; “The Road to Indigo” reading by poet Sandra Sarr, with music by Alex Cook; “The Importance of Blue” discussion by the Coco Tribe of Canneci Tinné with Chief Kugr Goodbear and Lou Ann Moses; an indigo-dyeing workshop with Ellie Barker and loom demonstration using Acadiana-grown brown cotton with Suzanne Chaillot Breaux and an exhibition of indigo-dyed artifacts from Acadiana, Africa, Asia, and Mesoamerica from her collection; “The Lost Science of Indigo in Histological Staining Demo and Presentation” with Dr. Brooke Dubansky and Dr. Ben Dubansky; “Bringing Back Lost Prairies” presentation and planting with Dr. Phyllis Griffard; and an indigo-seeding workshop, root demonstration, and prairie-burn discussion with Matthew Herron.

The “Le Bleu Perdu” project has sought to relearn the art and science of indigo as we restored lost and endangered Cajun Prairie habitat. Thanks to partnerships with Louisiana Indigenous leaders and natural dyeing experts, blue from indigo is once again being used for ritual objects. Just as we replanted the seeds of indigo in Louisiana soil, we hope that our actions will grow in the imagination of all who have participated in these programs.

“Le Bleu Perdu: The Lost Art, Science and Culture of Indigo” was made possible through the support of Getty, Mingei International Museum, the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. This program is funded under a grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, the state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this program do not necessarily represent those of either the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Notes

-

A. J. Braithwaite, “Something Blue: A Framework for the Physical Conservation and Intangible Cultural Heritage Revival of Indigo-Culture in the North American South” (master’s thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, 2021). For more on indigo in the Americas, see the essay by Jeffrey Splitstoser in this volume. ↩︎

-

Jenny Balfour-Paul, “Indigo in South and South-East Asia,” Textile History 30, no. 1 (1999): 98–112. ↩︎

-

A. Feeser, Red, White, and Black Make Blue: Indigo in the Fabric of Colonial South Carolina Life (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013); Braithwaite, “Something Blue.” ↩︎

-

Balfour-Paul, Indigo. ↩︎

-

Willem van Schendel, “The Asianization of Indigo: Rapid Change in a Global Trade around 1800,” in Linking Destinies: Trade, Towns, and Kin in Asian History (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2008), 29–49. ↩︎

-

Balfour-Paul, Indigo. ↩︎

-

James Alexander Robertson, ed., Louisiana under the Rule of Spain, France, and the United States, 1785–1807 (Freeport, N.Y.: Books for Libraries Press, 1911). ↩︎

-

J. D. L. Holmes, “Indigo in Colonial Louisiana and the Floridas,” Louisiana History 8, no. 4 (1967): 329–49. ↩︎

-

Braithwaite, “Something Blue.” ↩︎

-

G. Terry Sharrer, “The Indigo Bonanza in South Carolina, 1740–90,” Technology and Culture 12, no. 3 (1971): 447–55. For more on indigo in British South Carolina, see the essay by Andrea Feeser in this volume. ↩︎

-

Feeser, Red, White, and Black Make Blue; M. McKaty and M. Stewart, “Black, White, and Indigo: African Knowledge in The Grandissimes,” Southern Studies 14, no. 2 (2007): 106–29; Braithwaite, “Something Blue.” ↩︎

-

W. S. Coker, “Spanish Regulation of the Natchez Indigo Industry, 1793–1794: The South’s First Antipollution Laws?” Technology and Culture 13, no. 1 (1972): 55–58; Feeser, Red, White, and Black Make Blue. ↩︎

-

Sharrer, “The Indigo Bonanza in South Carolina”; Valérie Loichot, “Blues Indigo, Blès Indigo,” in La Louisiane et les Antilles, une nouvelle région du monde, ed. Alexandre Leupin and Dominique Aurélia (Guadeloupe: University of Antilles Press, 2019). ↩︎

-

Holmes, “Indigo in Colonial Louisiana and the Floridas.” ↩︎

-

Jenny Balfour-Paul, “Indigo and Blue: A Marriage Made in Heaven,” Textile Museum Journal 47, no. 1 (2020): 160–85. ↩︎

-

Balfour-Paul, Indigo. ↩︎

-

Loichot, “Blues Indigo, Blès Indigo”; McKaty and Stewart, “Black, White, and Indigo”; Balfour-Paul, “Indigo and Blue.” ↩︎

-

L. Jullien, “Sur une nouvelle methode de coloration des elements histologiques,” Lyon Médical 10 (1872): 526–30; George Clark and Frederick H. Kasten, History of Staining, 3rd ed. (Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1983). ↩︎

-

R. D. Lillie, Histopathologic Technic and Practical Histochemistry, 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965). ↩︎

-

Cajun Prairie Habitat Preservation Society website, https://www.cajunprairie.org. ↩︎

-

John K. Francis, ed., Wildland Shrubs of the United States and Its Territories: Thamnic Descriptions (Washington, D.C: U.S. Forest Service, 2004), 386, https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GOVPUB-A13-PURL-LPS90034[.]{.mark} ↩︎

-

David H. Rembert, “The Indigo of Commerce in Colonial North America,” Economic Botany 33 (1979): 128–34. ↩︎

-

New Georgia Encyclopedia, s.v. “indigo,” by James Bitler, last modified July 15, 2020, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/indigo. ↩︎

-

Acadiana Native Plant Project website, https://www.greauxnative.org. ↩︎

-

Kelli Foret Richard website, https://www.kelliforetartwork.com. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Balfour-Paul 1999

- Balfour-Paul, Jenny. “Indigo in South and South-East Asia.“ Textile History 30, no. 1 (1999): 98-112.

- Balfour-Paul 2000a

- Balfour-Paul, Jenny. Indigo. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2000.

- Braithwaite 2021

- Braithwaite, A. J. “Something Blue: A Framework for the Physical Conservation and Intangible Cultural Heritage Revival of Indigo-Culture in the North American South.“ Master’s thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, 2021.

- Clark and Kasten 1983

- Clark, George, and Frederick H. Kasten. History of Staining. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1983.

- Coker 1972

- Coker, W. S. “Spanish Regulation of the Natchez Indigo Industry, 1793-1794: The South’s First Antipollution Laws?“ Technology and Culture 13, no. 1 (1972): 55-58.

- Ehrenberg 1838/39

- Ehrenberg, C. G. Die Infusionsthierchen als. Leipzig: Volkommene Organismen Leopold Voss, 1838/39.

- Feeser 2013

- Feeser, Andrea. Red, White, and Black Make Blue: Indigo in the Fabric of Colonial South Carolina Life. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013.

- Frey 1993

- Frey, S. R. Review of Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century, by Gwendolyn Midlo Hall. American Historical Review 98, no. 2 (1993): 454-56.

- Holmes 1967

- Holmes, J. D. L. “Indigo in Colonial Louisiana and the Floridas.“ Louisiana History, 8, no. 4 (1967): 329-49.

- Jullien 1872

- Jullien, L. “Sur une nouvelle methode de coloration des elements histologiques.“ Lyon Médical 10 (1872): 526-30.

- Loichot 2019

- Loichot, Valérie. “Blues Indigo, Blès Indigo.“ In La Louisiane et les Antilles, une nouvelle région du monde, edited by Alexandre Leupin and Dominique Aurélia. Guadeloupe: University of Antilles Press, 2019.

- McKaty and Stewart 2007

- McKaty, M., and M. Stewart. “Black, White, and Indigo: African Knowledge in The Grandissimes.“ Southern Studies 14, no. 2 (2007): 106-29.

- Robertson 1911

- Robertson, James Alexander, ed. Louisiana under the Rule of Spain, France, and the United States, 1785-1807. Freeport, N.Y.: Books for Libraries Press, 1911.

- Sharrer, G. Terry. “The Indigo Bonanza in South Carolina, 1740-90,“ Technology and Culture 12, no. 3 (1971): 447-55.

- Sharrer, G. Terry. “Indigo in Carolina, 1671-1796.“ South Carolina Historical Magazine 72, no. 2 (1971): 94-103.

- Surrey 1922

- Surrey, N. M. M. “The Development of Industries in Louisiana during the French Regime 1673-1763.“ Mississippi Valley Historical Review 9, no. 3 (1922): 227-35.

- Van Schendel 2008

- Van Schendel, Willem. “The Asianization of Indigo: Rapid Change in a Global Trade around 180.“ In Linking Destinies: Trade, Towns, and Kin in Asian History, 29-49*.* Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2008.

- Winberry 1979

- Winberry, J. J. “Indigo in South Carolina: A Historical Geography.“ Southeastern Geographer 19, no. 2 (1979): 91-102.