In the mid-1700s, two women in British South Carolina produced handmade items that demonstrated their success with making dye from the indigo plant. Around 1752, planter Eliza Lucas Pinckney (1722–1793)—celebrated for establishing indigo as a staple in the colony—created a beautiful white silk wrap as a tribute to herself. It features indigo stems and leaves in a design that recalls paisley (Figure 1).1

The differences between Pinckney’s wrap and Hagar’s possible clothing speak volumes about the two women’s relationships to indigo. Pinckney’s refined handiwork reflects time that the planter was able to dedicate to individual pursuits. Hagar’s less detailed handiwork reflects a lack of available time that the enslaved woman had to devote to herself. However, her indigo-dyed attire demonstrates agency, for with blue, Hagar determined her own aesthetic.

Pinckney’s profit from indigo was shared by other planters in Britain’s colonies in southeastern North America: first in South Carolina and subsequently in Georgia and East Florida. South Carolina produced the most indigo by far, second only to rice in terms of an export good. South Carolina indigo was key to period dress. Blue was the most popular color for Europeans in the eighteenth century, and Britain dominated the textile industry; therefore, South Carolina indigo-dyed cloth circulated widely on both sides of the Atlantic. While Hagar may have worn blue attire colored with dye she had produced, she and other enslaved people, like Britons and their trading partners, likely wore garments with ready-made blue material that had been dyed in England with indigo produced on plantations. This material was even used by the very Native Americans whose lands had been stolen so that settlers could grow indigo. Thus, indigo made in South Carolina returned to the colony in the form of cloth. Consumers of this cloth were distanced from the conditions of slavery and the American Indian land dispossession that literally colored vast quantities of British textiles.

By figuratively pulling on a thread from Hagar’s garment to understand what enslaved labor on indigo plantations was like, we can observe these conditions, circumstances that made indigo a type of blue gold for planters and a huge burden for the enslaved who made success with the dye possible. We also can see that enslaved people were extraordinarily skilled and informed by indigenous African practices and that, in some instances, they were able to use their indigo-dyed clothing as a form of self-expression.

Enslaved Labor on Indigo Plantations

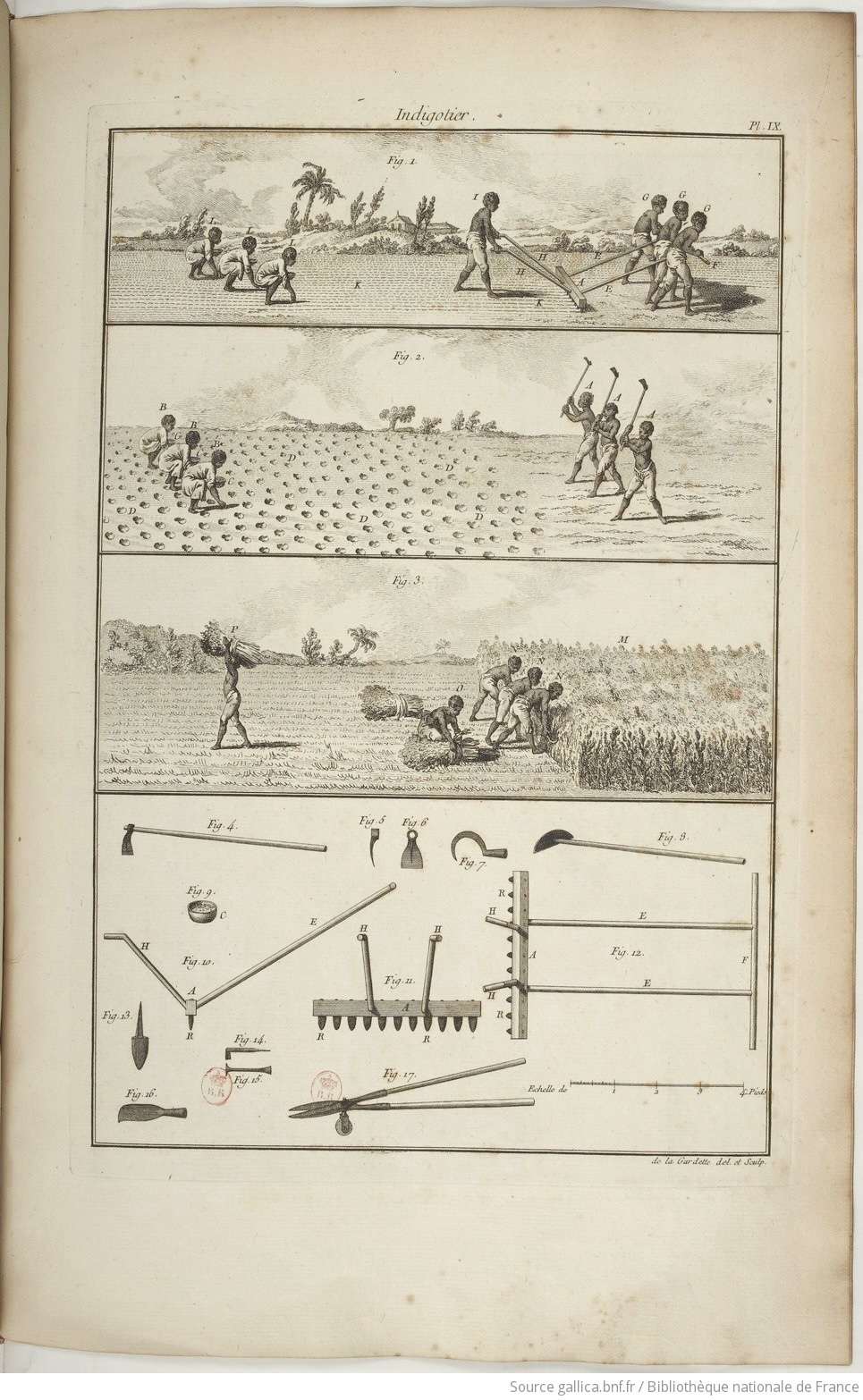

The depiction of indigo planting in M. de Beauvais Raseau’s 1770 L’art de l’indigotier illustrates the strenuous and demanding work performed by both male and female field hands. The illustration portrays enslaved people, both men and women, engaging in arduous labor, including hoeing, plowing, and planting seeds in a large field (Figure 4).

Their physical exertion is evident in their visibly engaged muscles and bare feet, with men pulling and pushing the plow, and women planting seeds in low, crouching positions. The symmetry of their movements suggests a coordinated approach to conserve energy and minimize unnecessary repetition. Despite the challenging conditions of working in warm and hot weather, the enslaved people demonstrated skillful working methods and coordination to make the demanding labor more bearable. This depiction not only conveys the order and control maintained under forced labor but also showcases the workers’ ability to develop efficient techniques for coping with the grueling work. The labor involved in maintaining the indigo crop, including plucking pests and weeds, further underscores the physically taxing nature of indigo cultivation. Overall, the illustration portrays the physical and mental challenges faced by the enslaved in producing strong and healthy plants while striving to minimize discomfort and optimize their efforts.

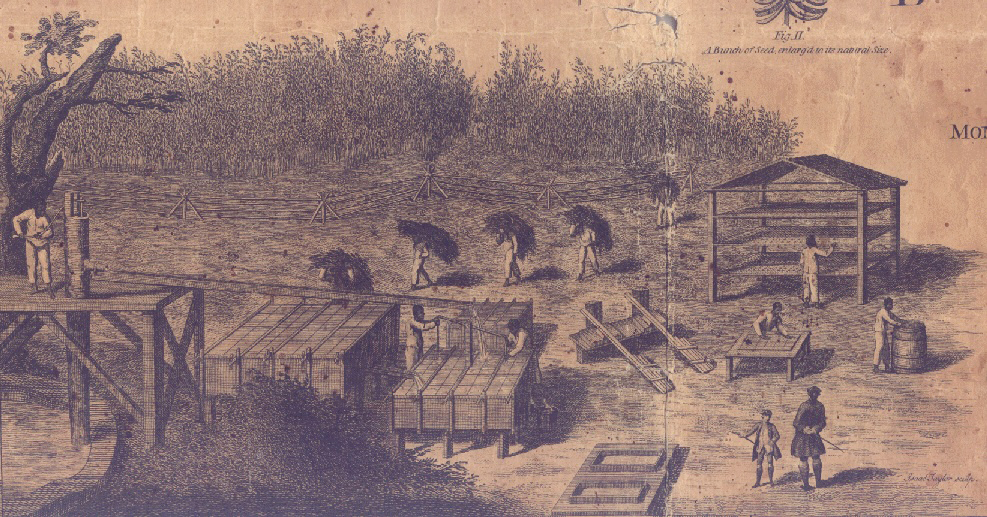

Similarly, the arduous nature of harvesting and processing indigo plants is evident in Henry Mouzon’s 1773 map of Saint Stephen Parish. The image highlights the physical labor involved, with enslaved people depicted bent over as they transport cut indigo to vats for dye making, while a planter and overseer are shown supervising the labor in upright postures (Figure 5).

This portrayal underscores the taxing nature of the work of the enslaved, as they are burdened by large bundles of indigo stalks, as well as the repetitive aspects of their tasks. Additionally, the image includes details such as workers managing the water supply to the vats and ensuring that the indigo remains submerged under weights. Although the depiction does not show the beating of the fermented liquid resulting from the immersed plant matter, it prominently displays long and thick paddles used for this purpose. The image also illustrates enslaved people cutting dye cakes from the dried material that is produced by beating and straining the indigo liquid. Furthermore, others are shown stacking these cakes in a shed for more drying, and then packing them in barrels for shipment. The person engaged in cutting the dye squares seems to be female, and we know that Hagar did this expert work.

Historical documentation of indigo dye production shows that in the seventeenth-century Caribbean, British and European plantation labor organization practices relied on indigenous African expertise in indigo making. In Barbados, British colonizers adopted the Spanish model of an indigo workshop run by enslaved people, who were observed employing dye-making techniques influenced by African practices. These included the use of hollowed-out logs for soaking plants, followed by pounding with mortars and pestles—a method with roots in Africa.3 Additionally, when British and European merchants introduced South Indian indigo production methods in the Caribbean, which involved multiple vats and an extensive beating process, the resulting larger-scale operations necessitated the use of wood paddles and, in certain plantations, wooden vats. The construction of this dye-making equipment required significant woodworking skills, which many workers had acquired in their homelands.4 Consequently, indigenous African knowledge became integrated into Caribbean indigo manufacturing processes alongside South Indian, European, and British techniques and procedures. These combined methods were transmitted to South Carolina by Barbadian colonists, who brought instructions and seeds to their new settlement.5 While their initial attempts at establishing indigo were not successful, later indigo experiments in South Carolina, like Pinckney’s, were.

African expertise in indigo cultivation and dye production was also brought to South Carolina directly. Many enslaved people who arrived in the colony during the indigo boom, spanning from the late 1740s until the Revolution, originated from regions in Africa where indigo was grown and processed into dye.6 The presence of depressions known as indigo pits on the grounds of a former indigo plantation on Edisto Island suggests this likelihood.7 Africans such as the Yoruba of Benin, the Manding of Mali, and the Hausa of Kano were esteemed for their indigo-making and dyeing skills for centuries, with the latter using pit vats to dye cloth.8 Though African blue dye is typically generated by burning indigo plant material and shaping the ash into small balls, remnants from vats can also be a significant component of the dye.9 Therefore, it is plausible that Africans employed their native expertise in dye making and dyeing at an Edisto indigo operation.

Clothing and Self-Expression

In South Carolina, as in other British territories, enslavers sometimes provided their domestic workers with fine clothing, either to showcase the elegance of their household or out of genuine affection for those closest to them. However, when it came to their field hands, plantation owners primarily supplied them with clothing for basic survival. Typically, men and women were given fabric for a single set of clothes for summer and another for winter, along with a blanket every three years.10 Some had shoes and stockings, while others did not, and some received caps or handkerchiefs to wear on their heads. Some enslaved people were expected to fashion their own attire, a task they usually preferred, as the plantation mistress and her female helpers or a hired tailor often produced standard items with little concern for achieving a good fit.11 Most slave garments were crafted from inexpensive, rough, and unadorned fabric, although the South Carolina 1740 slave code allowed for a little variety: some colors and designs, primarily checks and stripes, were permitted.12

Despite such legal regulations, individuals in bondage were able to honor their African heritage through a significant garment—the head wrap—and through a fusion of aesthetics in which the color blue was used to convey African notions of power and protection. Drawing from not only the accounts of former enslaved people but also interviews with present-day Gullah people (descendants of those from the South Carolina and Georgia Sea Islands known for their culturally African-influenced traditions) and works by African American writers dedicated to preserving historical memory, researchers argue that the contemporary association of blue with protection among modern Lowcountry African Americans aligns with discoveries of blue-beaded amulets at slave mortuary sites. Testimony reveals that well into the twentieth century, descendants of enslaved people possessed personal charms that were predominantly blue, and even today, some Gullah individuals paint the trim of their doors and windows blue to ward off malevolent spirits.13 It is possible that some workers used remnants from indigo vats for this, and considering that many of the enslaved people who were brought to South Carolina were familiar with African indigo-dyed fabric, blue and indigo dye certainly played a role in how they presented themselves through their attire.

This is illustrated in the December 19, 1770 edition of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette, which featured a plantation owner’s advertisement for a runaway from Angola. The master detailed the clothing worn by this man, as it served as a helpful identifier for the fleeing individual. He wore a suit made of “white negro cloth . . . with some blue between every seam, and particularly on the fore part of the jacket, a slip of blue in the shape of a serpent.” Through this embellishment of indigo dye, the enslaved man adorned his garment with the creature that many Africans regarded as an intercessor with ancestors and a symbol of fertility.14 This indigo decoration thus connected the man not only to his people’s past but also to their future.

The indigo-dyed ensemble Kendra Johnson produced for Hagar, dyed with indigo by Karen Hall, is a beautiful and fitting tribute to the power of indigo in the experience of enslaved people. Though the gorgeous blue enriched their masters, the dye they made more importantly reflected their remarkable skilled labor and African lifeways.

Notes

-

This wrap is in the possession of Pinckney’s descendant Tim Drake, who kindly made it available to me for inspection. ↩︎

-

Planter and merchant Henry Laurens recommended Hagar’s skills to his overseer. See The Papers of Henry Laurens, vol. 15, December 11, 1778–August 31, 1782, ed. David R. Chesnutt, C. James Taylor, Peggy J. Clark, and Laura L. Graham (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Historical Society, 1968), 306n6. ↩︎

-

Frederick C. Knight, Working the Diaspora: The Impact of African Labor on the Anglo-American World, 1650–1850 (New York and London: New York University Press, 2010), 93–94. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 97. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 100. ↩︎

-

Virginia Gail Jelatis maintains that Africans enslaved in South Carolina were frequently from regions where indigo was grown and used in dyeing cloth. Knight notes that mid-eighteenth-century South Carolina indigo planters preferred enslaved people from Senegambia, which had a long history of indigo production. Drawing on these facts, both scholars suggest that Africans with direct experience making indigo used their skills in South Carolina. See Jelatis, “Tangled Up in Blue: Indigo Culture and Economy in South Carolina, 1747–1800” (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1999), 152–53; Knight, Working the Diaspora, 104–8. ↩︎

-

Charles Spencer, Edisto Island, 1663 to 1860: Wild Eden to Cotton Aristocracy (Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2008), 69. This possibility is evocatively portrayed in Julie Dash’s 1991 film Daughters of the Dust: one scene shows enslaved workers dyeing material in such pits. ↩︎

-

Kate P. Kent, review of Into Indigo: African Textiles and Dyeing Techniques, by Claire Polakoff, African Arts 14, no. 1 (November 1980): 28. ↩︎

-

Duncan Clarke, “Indigo in West Africa: An Introduction,” Adire African Textiles, February 13, 2010, accessed November 15, 2023, http://adireafricantextiles.blogspot.com/2010/02/indigo-in-west-africa-introduction.html. ↩︎

-

Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1998), 126. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 129. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 127–28; Kathleen Staples, “‘Useful, Ornamental, or Necessary in This Province’: The Textile Inventory of John Dart, 1754,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 29, no. 2 (2003): 61. ↩︎

-

Staples, “Useful, Ornamental,” 62–64. ↩︎

-

Linda Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2002), 136. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Baumgarten 2002

- Baumgarten, Linda. What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America. New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2002.

- Clarke 2010

- Clarke, Duncan. “Indigo in West Africa: An Introduction.“ Adire African Textiles, February 13, 2010, accessed November 15, 2023, http://adireafricantextiles.blogspot.com/2010/02/indigo-in-west-africa-introduction.html.

- Jelatis 1999

- Jelatis, Virginia Gail. “Tangled Up in Blue: Indigo Culture and Economy in South Carolina, 1747–1800.“ PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1999.

- Kent 1980

- Kent, Kate P. Review of Into Indigo: African Textiles and Dyeing Techniques by Claire Polakoff. African Arts 14, no. 1 (November 1980): 28–29.

- Knight 2010

- Knight, Frederick C. Working the Diaspora: The Impact of African Labor on the Anglo-American World, 1650–1850. New York and London: New York University Press, 2010.

- Laurens 1968

- The Papers of Henry Laurens, vol. 15, December 11, 1778–August 31, 1782. Edited by David R. Chesnutt, C. James Taylor, Peggy J. Clark, and Laura L. Graham. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press for the South Carolina Historical Society, 1968.

- Morgan 1998

- Morgan, Philip D. Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake and Lowcountry. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1998.

- Spencer 2008

- Spencer, Charles. Edisto Island, 1663 to 1860: Wild Eden to Cotton Aristocracy. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2008.

- Staples 2003

- Staples, Kathleen. “‘Useful, Ornamental, or Necessary in This Province’: The Textile Inventory of John Dart, 1754.“ Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 29, no. 2 (2003): 39–82.