Indigo-resist prints using two shades of blue, found in various museums and private collections, have long been a source of curiosity, admiration, and mystery. For our 2015 book on indigo, our research showed a correlation with African artists in America, where some of these textiles were created.1 These amazingly detailed prints were made by multiple artists, using a variety of methods. While researching, we divided textiles into groups and wrote about several of these groups. With limited time for research, though, we did not include what we now refer to as the Bermuda group of textiles, discussed here.2

These mysterious indigo-resist textiles have often been dated as a group because of a single textile held at the Albany Institute of History and Art. It contains an excise stamp that seems to place its date of creation around 1766.3 However, at St. George’s Historical Society in Bermuda, a group of similar indigo-resist textiles, donated to the museum by descendants of the artists, are stored with the note “woven by J. Stirrop and R. Wright on Longbird Island in 1656.”4 This dating would mean that some of the textiles were created more than a hundred years earlier than the textile with the tax stamp. Since family histories can be less than reliable, we sought evidence to support the information associated with this group of textiles. Could written documentation exist to place the textiles in the seventeenth century?

The History of Bermuda and the Weavers of Longbird Island

The archipelago of Bermuda was discovered by accident in 1505 by Spanish navigator Juan Bermúdez, who reportedly left several sets of pigs on “the rock” to aid other travelers or those who were shipwrecked. More than a century later, in 1609, a flotilla of seven ships left England with passengers and supplies for the founding colony of Jamestown. When the flotilla sailed into a storm, the Sea Venture’s captain decided to steer his flagship onto Bermuda’s reef to prevent it from sinking. Everyone on the ship was saved, and the settlers soon became unwilling to move on after hearing about the dire conditions in Jamestown. Thus, the rock was claimed for the English crown in 1612, and an intentional British settlement of the isle began.

The Virginia Company ran the settlement until 1615, when the Company of the City of London for the Plantacion [sic] of The Somers Isles (SIC - Somers Isles Company) was formed to operate the colony. The SIC hired Richard Norwood to conduct a survey of the isles and divide the shares, a project he worked on until 1616. In the published survey, SIC weavers Stirrop and Wright were assigned to Longbird Island. Although their exact arrival date is unknown, it is inferred to be 1613, when the survey began. The year 1616 marks the intentional planting of cassava (manioc, sometimes used as a paste for the resist process) as a subsistence crop, and cassava would later become one of the island’s main exports.

Indigo was one of many crops planted in Bermuda to sustain the colony. Enslaved people helped with this work. Black Bermudians contributed to society by teaching the white Bermudians skills they had brought with them. West Africans helped with growing techniques, the use of cassava, and fishing.5 As early as 1624, it is noted that enslaved people wove homegrown Sea Island cotton into cloth dyed with indigo. The early inhabitants had little clothing, so cotton was ordered to be grown on every share of the land. In 1625, the SIC requested more indigo seeds or plants.

Norwood’s second survey, published in 1626 by John Speed, showed Longbird Island to be in the “tenure and occupation of #14 John Stirrop and Ralph Wright[,] weavers,” with a total of forty-six acres.6 The next official record of the weavers is a colonial record from 1645, when a mariner “sold unto James Stirrup of the Summer Islands, weaver, one Indian woman named Nell, aged about 20 years, to have and to hold for the term of fourscore and nineteen years if she should so long live.”7 That same year or perhaps the next (the record is difficult to read), it was documented that “Lawrence Pitcher hath put his daughter Elizabeth apprentice unto Ralph Wright of Longbird Island, weaver, and to his wife and their assigns, for the term of 9 years.”8 Thus began the creation of a team of workers to create textiles.

The Stirrop/Wright workshop members would include Stirrop (an SIC weaver) and his wife, Elizabeth Stirrop. The Indian slave Nall, or Nell, “no doubt had knowledge of weaving”9 and could have been aware of Indian textile-printing methods. An Indian girl, “Two Negroes,” and the indentured servant Thomas Atkins worked with them.10 The workshop also included Wright (another SIC weaver) and his wife, Elizabeth Wright, the male Indian slave Whan, and two indentured servants, Elizabeth Pitcher and Elizabeth Jourdan.11

In 1656–57, a general letter from the SIC, dated October 14, 1656, was sent by John Jenkins and delivered by Capt. Limbrey, who arrived in Bermuda on November 7, 1657. In one section, the letter states: “We have considered your comments touching the two weavers of dimity, Stirrop and Wright, which long ago were sent over by the Company and assigned accommodation on Longbird Island. Send us an account by this ship whether . . . they have continued their weaving.”12

On May 28, 1658, an SIC order stated, “Jeames Stirrup and Ralph Wright are settled in Longbird Island by [order] from the Company: Therefore we require they be not molested.”13 One historian stated that this was because the weavers were so busy they should not be bothered. Local Bermudian production grew to the point that it began replacing English goods, and they were building an economy that required maritime links with the North American colonies.14 Bermudians began launching their own trading vessels in the 1650s, extending their trade with neighboring colonies.15 In fact, the Atlantic colonies would become known for printed blue cloth, as shown in a petition presented to the British House of Commons, which “explained that hundreds of people worked raw cotton from the colonies into fabric, ‘which has usually been printed, or dyed blue.’”16

In 1660, one of the Navigation Acts restricted Bermuda’s access to other ships trading there and limited its intercolonial maritime trade. In 1663, the SIC banned shipbuilding in Bermuda.17 Bermudians resisted the SIC’s bidding, though, refusing to plant the required crops, and they did their best to maintain the economic status quo.18

The Bermuda workshop would continue for many years with the indentured and enslaved continuing the work until the death of Stirrop. At his death, his estate included the enslaved people, two boats for transporting goods, and fabric. In 1665, when Stirrop died, none of his children continued his work. They all chose different careers. By 1682, Elizabeth Stirrop was unable to pay the rent and was evicted from the land. Wright continued his weaving work, but without access to colonial markets, this would have been more difficult. In 1684, the SIC that had provided the land to him for his weaving work was dissolved, and the British government took over. His children chose other professions. While Wright’s date of death is unclear, we know that he was not alive in 1691, when all men were required to take an oath of loyalty to the Crown. The family members kept whatever fabric had not been sold on bolts as well as those items that had been made into bed hangings. These items were documented by outside sources at several periods of time, including when some of the fabric had deteriorated beyond saving.

The Calico Acts, the Stamp Acts, and similar legislation were designed by the Crown and Parliament to turn the Atlantic colonies into consumers of British goods, instead of creators. Even though weavers continued to work in the colonies, with a steady production, they could not trade outside the area. These facts caused textile historians to overlook commercial textile production in the colonies.

The Textiles of the Stirrop/Wright Workshop

The two SIC weavers were known as “weavers of dimity,” but the fabrics now at St. George’s Historical Society, passed down through the Wright family, show that the workshop eventually broadened the scope of its weaving.

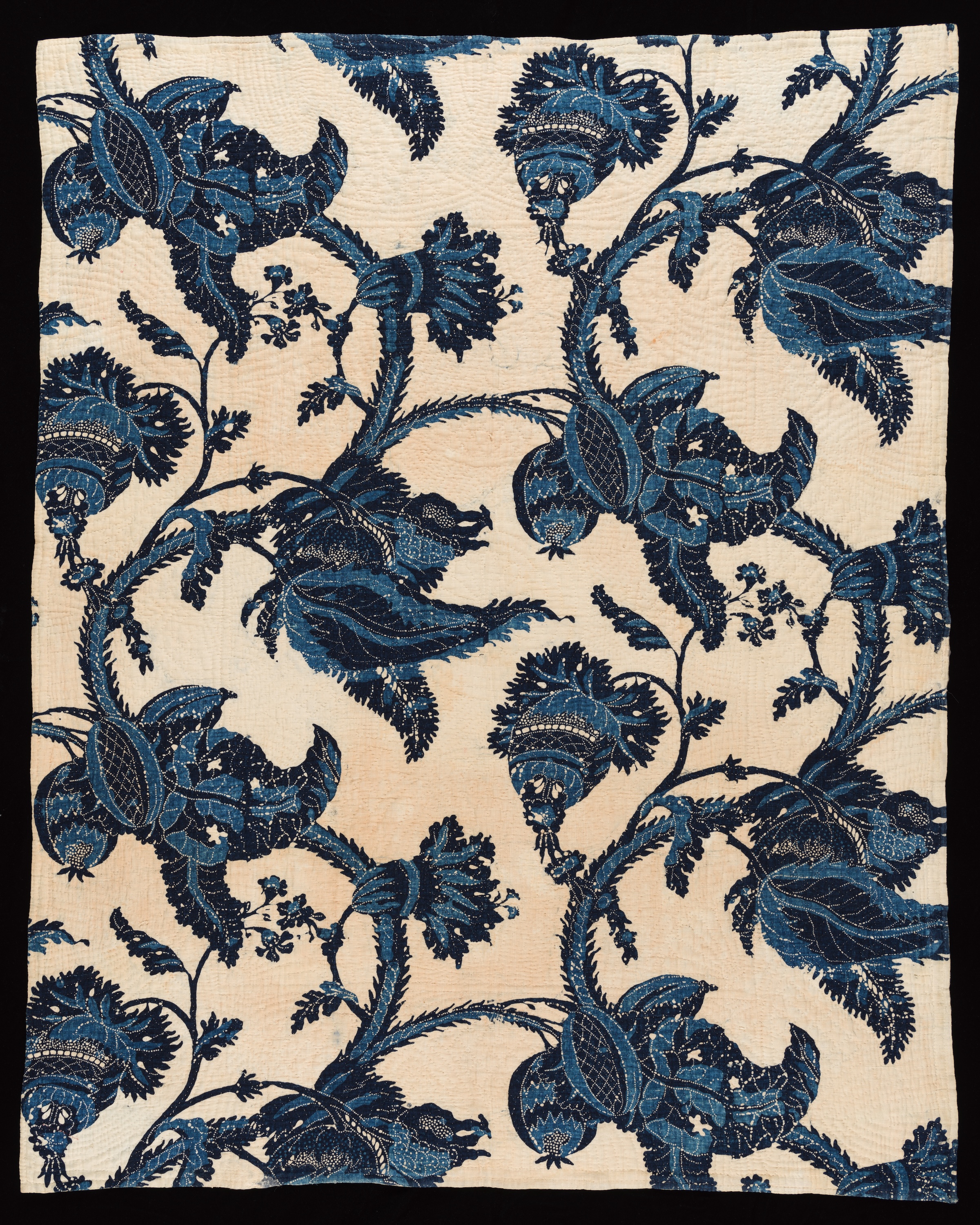

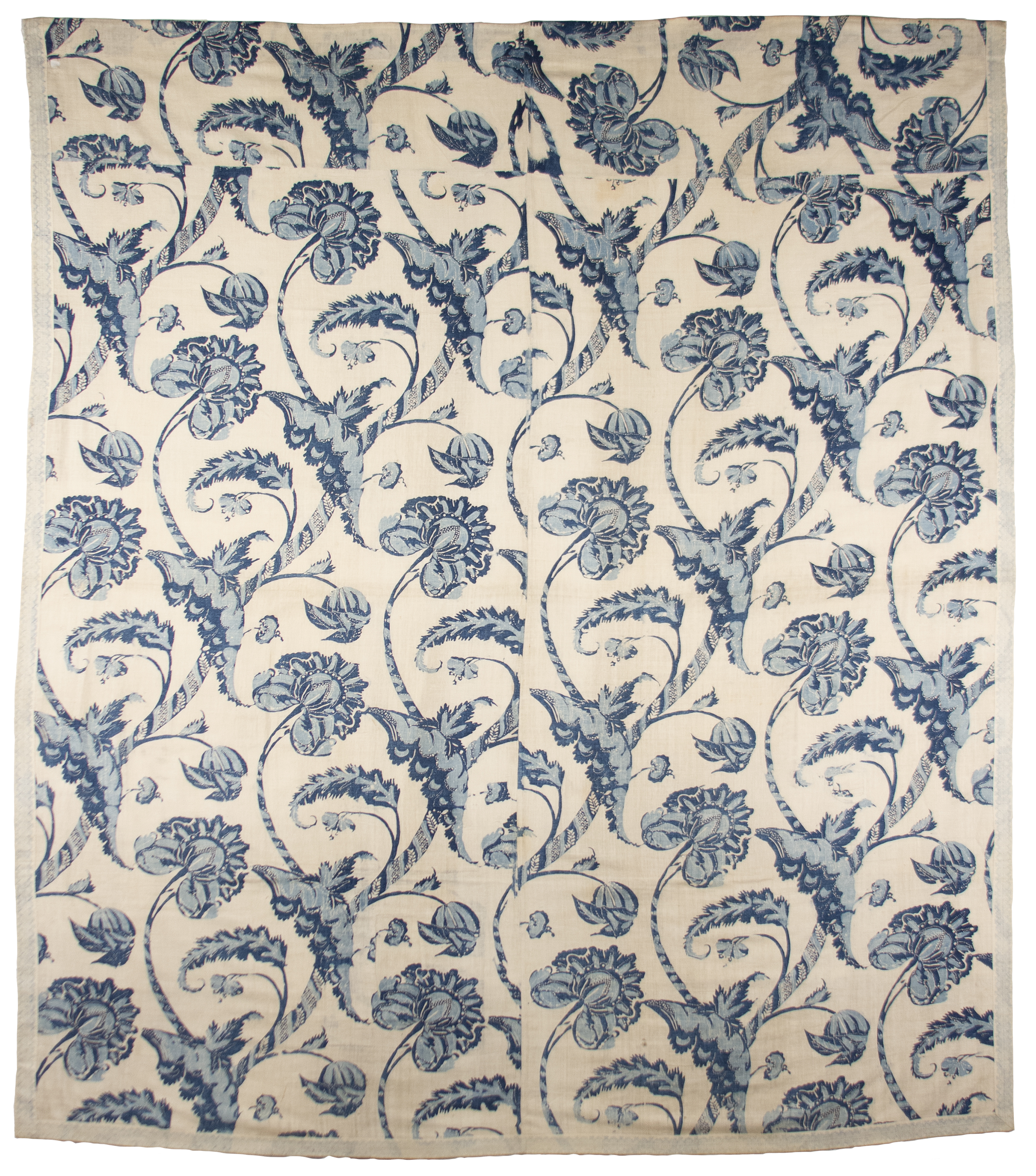

Of the fabrics still in existence, the following patterns remained: Night Blooming Cereus, Cereus Day/Fancy Tassel, Pin Cushion Flower, Flower Vine Tape, Undulating Vine Tape, Crossed Vine Tape, and a stripe (Figures 1–3). A written record also existed of the Pomegranate pattern, as well as an old photograph of the cloth hanging on a wall in the historical society.19 The records indicated that the bolt of fabric had deteriorated and was destroyed.

The Bermuda workshop textiles comprise the following fibers: linen, cotton, or combinations of these materials. The fabrics have large-scale designs, with a design within a design on the stems as well as on the flowers. The textiles also include white dots of more than one size, unlike the French picotage, which has only one size of dots, made with brass pins driven into the wooden printing blocks. The workshop’s designs all relate to the island around the textile artists, reflecting the flora and fauna of Bermuda.20 There are no “tree of life” or geometric designs typical of other locales. One unusual hallmark is the use of indigo-resist tape or binding.

Once we established these characteristics of the Bermuda group, we found similar patterns at museums and collections in the United States and matched them using the design and/or diagnostic “tape” as binding (Figures 4–5). These patterns include but are not limited to Bud with Four Leaves, Halo Flower, Two Flowers, Tulips & Anemone, Cahows, Rooster & Pomegranate, Chicken, Peacock, Fancy Bird, Star Flower, Hawk & Pineapple, Pomegranate, and Spiked Flowers. (The majority of these names were assigned by researchers to help with tracking.)

Several of the Bermuda workshop designs were reproduced or copied in later centuries, such as Chicken/Pheasant and Pomegranate, as well as Bud with Four Leaves, sometimes over several centuries. So, a textile with one of these designs was not necessarily created by the Bermuda workshop. Also, since these artifacts had previously been dated according to the single textile with the excise tax stamp, it was important to establish proof of the existence of the Bermuda group of textiles on the mainland prior to the 1766 date.

As shown through the petition to the House of Commons, blue-printed and -dyed textiles were transported for sale in the Atlantic colonies. A sales record book of the merchant Hendrick Van Rensselaer of Schenectady, New York, shows multiple sales of blue-and-white print fabric as early as 1734.21 Widow Van Cortlandt of Albany, related by marriage to the Van Rensselaer family, noted in her 1724 will that she owned blue-and-white curtains.22 Finally, attorney Thomas Witter, who appears to have worked as a loan shark during the early 1700s, had records of reclaiming people’s personal property, including bedding from such islands as Bermuda and Jamaica, and reselling the property in New York.23

Finally, one complexity we found in our research is that three of these designs partially match paper patterns clipped into a Baker, Tuckers & Co. scrapbook in England.24 This does not mean that the design was created by Baker, Tuckers & Co. This scrapbook includes patterns from multiple companies, some dated to the 1600s. Textile companies collected patterns from other companies, such as when another firm went out of business. After a block was cut, it was tested by printing on paper, which was then kept as a record or used by another company as an idea for designs.

In the case of these blocks, which were resist blocks, the color would have been painted into the design to show the image created. In the pattern book, the color varies among the resist patterns, possibly because paint did not accurately represent the true indigo color. Additionally, part of the original full block design is missing, perhaps because Baker, Tuckers & Co. was known as a botanical print company. So, there was no reason to save the bird portion of the design. Finally, Baker, Tuckers & Co. was a silk printer, primarily producing handkerchiefs, with no record of using these designs in either silk or cotton. Perhaps the paper versions of the patterns made their way to England when Stirrop and George Tucker took the Somers merchant ship from Bermuda to England in 1657.25

Much more research needs to be done on the indigo-resist textiles from Bermuda. Our next steps include compiling a comprehensive list of Bermuda textiles at institutions and notifying curators and owners of the newly documented timeline and creation site. We also plan to establish criteria for identifying which textiles were part of the original Bermuda workshop, and which ones were inspired by the Bermuda textiles but created later.

Notes

-

Kay and Lori Lee Triplett, Indigo Quilts: 30 Quilts from the Poos Collection; History of Indigo (Lafayette, Calif.: C & T Publishing, 2015), 6–43. ↩︎

-

We originally referred to this group of textiles as the “Island Group” because of one of the Albany merchant papers. However, after reading a dissertation that located a similar group of textiles at St. George’s Historical Society, we have referred to this textile set as the “Bermuda group.” See Mary Elizabeth Gale, “Indigo-Resist Prints from Eighteenth-Century America: Production and Provenance” (master’s thesis, University of Rhode Island, 2001). ↩︎

-

Indigo-resist fabric, Albany Institute of History and Art, 1948.31.113. See Henry Dagnall, The Marking of Textiles for Excise & Customs Duty (Queensbury, UK: Henry Dagnall, 1996), 21–25. ↩︎

-

Intake note in box, St. George’s Historical Society, Bermuda. ↩︎

-

Michael J. Jarvis, In the Eye of All Trade: Bermuda, Bermudians, and the Maritime Atlantic World, 1680–1783 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 31–32. ↩︎

-

Transcribed in J. H. (John Henry) Lefroy, Memorials of the Discovery and Early Settlement of the Bermudas or Somers Islands, 1515–1685 (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1879), 647. Stirrop’s surname is alternately spelled “Stirrup,” and his first name is given variously as “John,” “James,” and “Jeames.” Wright’s surname is sometimes spelled “Wrighte” and “Righte,” and his first name is given variously as “Ralph” and “Ralfe.” ↩︎

-

A. C. Hollis Hallett, ed., Bermuda under the Sommer Islands Company 1612–1684: Civil Records, 3 vols. (Bermuda: Juniperhill Press and Bermuda Maritime Museum Press, 2005), 3:267. ↩︎

-

Hallett, Civil Records, 3:342. ↩︎

-

Virginia Bernhard, Slaves and Slaveholders in Bermuda, 1616–1782 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999), 58. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 113. ↩︎

-

Hallett, Civil Records, 3:308, 342, 369–70. ↩︎

-

Hallett, Civil Records, 1:400. The definition of dimity varies by culture and period. In this case, it is a cotton fabric, having at least two warp threads thrown into relief to form fine cords. It was a cloth commonly employed for bed upholstery and curtains in the seventeenth century. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 1:422. ↩︎

-

Jarvis, In the Eye of All Trade, 42. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 52. ↩︎

-

Jonathan Eacott, Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600–1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 112. ↩︎

-

Jarvis, In the Eye of All Trade, 53. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 55. ↩︎

-

Charles Wilson, “A Lost Art and Dead Industry of Bermuda,” The Bermudian, November 1935, 22. ↩︎

-

For example, Night Blooming Cereus and Pomegranate were names given by the Bermudians. Although the Cereus is not native to Bermuda, it became part of the flora of the isle after Captain Thomas Newbold planted it at his cottage in Hamilton. It now grows all over the various islands. ↩︎

-

Hendrick Van Rensselaer, Account Book for Sales in Schenectady 1734–1789, Albany Institute of History and Art, BND 007. ↩︎

-

Wessel and Dirck Ten Broeck, Ten Broeck Family Papers, Albany Institute of History and Art, AE 117. ↩︎

-

Thomas Witter, Witter Papers 1745–1833, New York Public Library Research Collection, Archives and Manuscripts. ↩︎

-

Mary E. Gale and Margaret T. Ordoñez, “Eighteenth Century Indigo-Resist Fabrics: Their Use in Quilts and Bed Hangings,” in Uncoverings 2004, ed. Kathlyn Sullivan, Research Papers of the American Quilt Study Group 25 (Lincoln, Neb.: American Quilt Study Group, 2004), 157–79. ↩︎

-

Hallett, Civil Records, 1:400. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Bernhard 1999

- Bernhard, Virginia. Slaves and Slaveholders in Bermuda, 1616–1782. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999.

- Dagnall 1996

- Dagnall, H. The Marking of Textiles for Excise & Customs Duty. Queensbury, UK: Henry Dagnall, 1996.

- DuPlessis 2016

- DuPlessis, Robert S. The Material Atlantic: Clothing, Commerce, and Colonization in the Atlantic World, 1650–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Eacott 2016

- Eacott, Jonathan. Selling Empire: India in the Making of Britain and America, 1600–1830. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

- Evans 1938

- Evans, Walker. American Photographs. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1938.

- Gale 2001

- Gale, Mary Elizabeth. “Indigo-Resist Prints from Eighteenth Century America: Production and Provenance,” Master’s thesis, University of Rhode Island, 2001.

- Hallet 2005

- Hallet, A. C. Hollis, ed. Bermuda under the Sommer Islands Company 1612–1681: Civil Records. 3 vols. Bermuda: Juniperhill Press & Bermuda Maritime Museum Press, 2005.

- Jarvis 2010

- Jarvis, Michael J. In the Eye of All Trade: Bermuda, Bermudians, and the Maritime Atlantic World, 1680–1783. Chapel Hill: University North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Jarvis 2022

- Jarvis, Michael J. Isle of Devils, Isle of Saints: An Atlantic History of Bermuda, 1609–1684. Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 2022.

- Jones 2022

- Jones, Elizabeth. “The Lost Island of Long Bird,” The Bermudian, May 29, 2022.

- Keefer 2022

- Keefer, Donald A. “Historical Collection of Donald A. Keefer: Robert Sanders.” Schenectady Public Library, accessed July 22, 2022.

- Lefroy 1879

- Lefroy, J. H. (John Henry). Memorials of the Discovery and Early Settlement of the Bermudas or Somers Islands, 1515–1685. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1879.

- Lynd 1929

- Lynd, Robert S., and Helen Merrell Lynd. Middletown: A Study in American Culture San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1929; reprint, Harvest/HBJ, 1956.

- Matson 1998

- Matson, Cathy. Merchants and Empire: Trading in Colonial New York. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1998.

- McCallan 1948

- McCallan, E. A. Life on Old St. David’s, Bermuda, Hamilton: Bermuda Historical Monuments Trust, 1948.

- Mercer 1982

- Mercer, Julia E. Bermuda Settlers of the 17th Century. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1982.

- Packwood 1975

- Packwood, Cyril Outerbridge. Chained on the Rock: Slavery in Bermuda, New York: E. Torres, 1975.

- TenBroeck 2022

- TenBroeck, Wessel, and Dirck TenBroeck. TenBroeck Family Papers. Albany Institute of History and Art, AE117, accessed July 21, 2022.

- Triplett and Triplett 2015

- Triplett, Kay, and Lori Lee Triplett. Indigo Quilts: 30 Quilts from the Poos Collection; History of Indigo. Lafayette, Calif.: C&T Publishing, 2015.

- Van Rensselaer 2022

- Van Rensselaer, Hendrick. Account Book for Sales in Schenectady 1734–1789. Albany Institute of History and Art, BND 007, accessed July 21, 2022.

- Wilson 1935

- Wilson, Charles. “A Lost Art and Dead Industry of Bermuda.” The Bermudian, November 1935.

- Wilson 1967

- Wilson, Charles Pearman. “Ancient Craft Revived.” The Bermudian, November 1967.

- Witter 2022

- Witter, Thomas. Witter Papers 1745–1833. New York Public Library Research Collection, Archive & Manuscripts, accessed July 17, 2022.