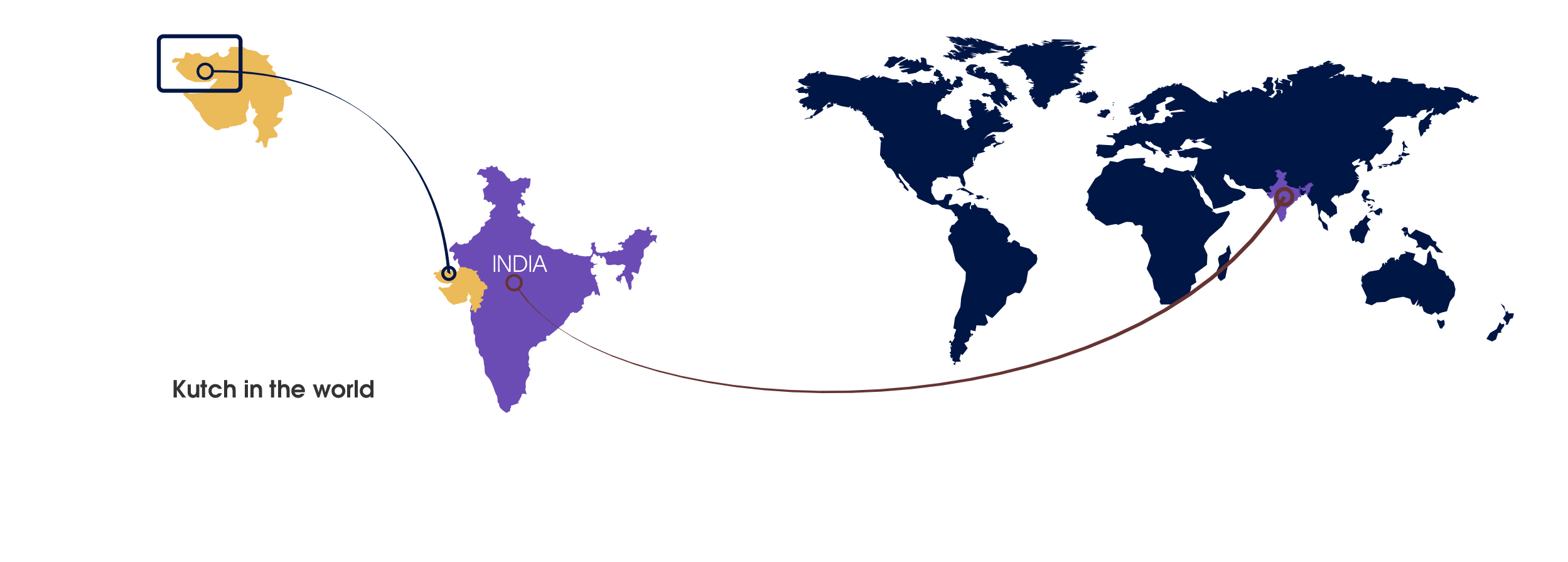

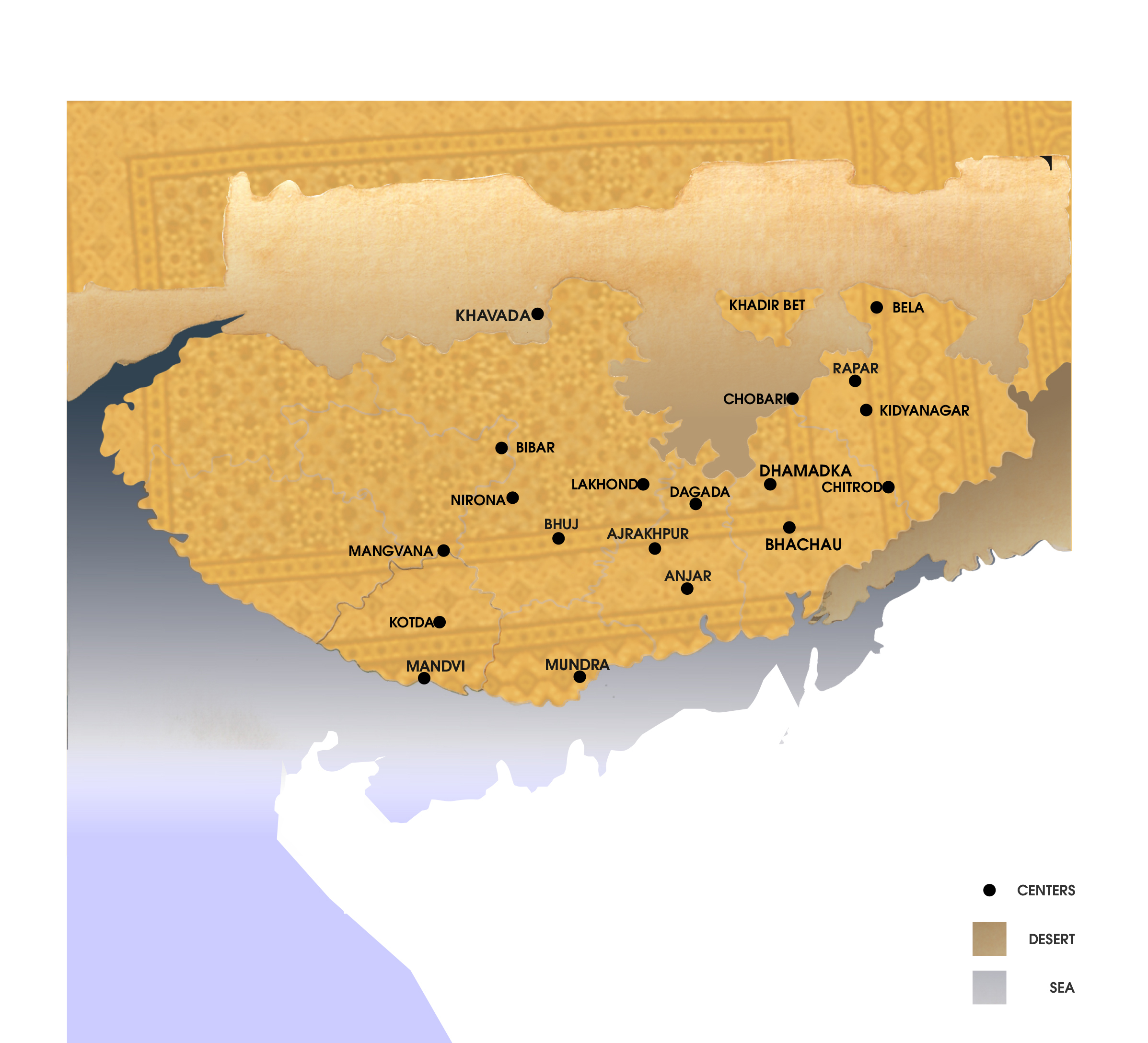

Kutch, an arid region in western India, is politically a district of the state of Gujarat (Figures 1.1-1.2) Physically and culturally, it is an island between the province of Sindh, Pakistan, and mainland Gujarat. Indigo was historically grown in both Kutch and Sindh.

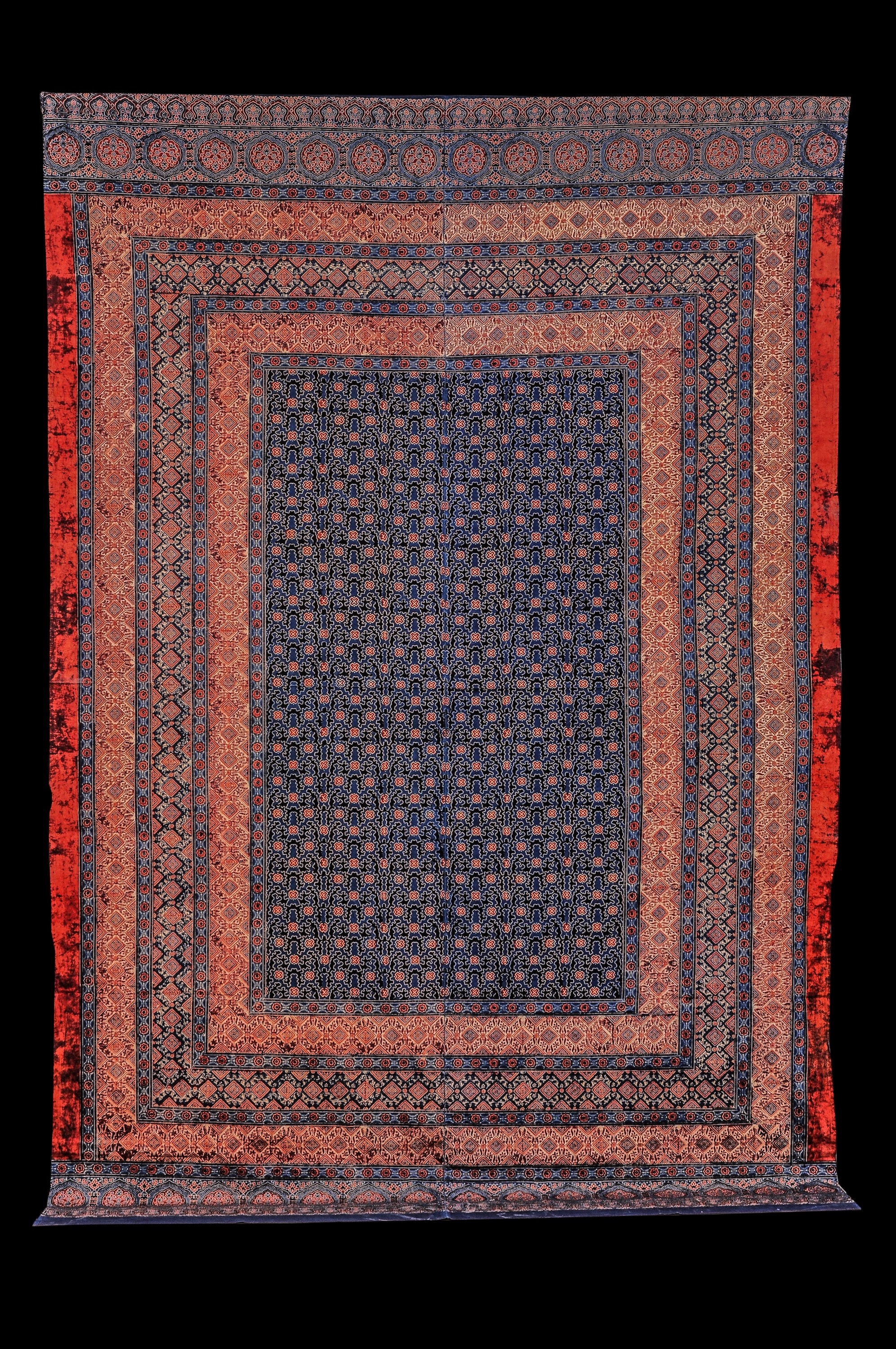

Rao Bharmalji wanted Ajrakh, the story goes. This legendary cloth, called the national cloth of Sindh, is traditionally blue with red, black, and white patterns of classic Islamic style, based on mizan (balance or order) and geometry.1 The colors are created with a complex process of resist and mordant printing, and dyeing with indigo, madder, and iron acetate (Figure 3).

An Ajrakh, a rectangular cloth, made in two parts stitched together, has a fixed set of multiple borders on its long and short sides, and a field with one of about sixteen patterns. Each pattern is created with impressions of three blocks, an outline called rekh, and two filling patterns called datlo—one for each color; all patterns must register. In the most traditional version, the fabric is painstakingly printed on both sides with exact registration, dyed, washed, and then printed on both sides and dyed again. This creates deeper shades of indigo and madder, extends the life of the cloth, and enables it to be used as a turban or shoulder cloth in which no reverse side shows.

Skilled carving of the fine symmetrical woodblocks is crucial. This, combined with registration of multiple block impressions; knowledge of the complex chemistry of resist, mordant, and natural dye substances; and expertise in dyeing enabled Ajrakh artisans to take the art of block printing to its zenith (Figure 4).

It must be emphasized that the knowledge of traditional artisans is inherited, experiential, and embodied. It organically combines art and science into one whole. The late Ajrakh master Mohmedbhai Siddique Khatri of the village of Dhamadka in Kutch understood indigo to be a living substance. He could taste a dye bath and know if it needed lime, soda ash, or dates. In Kutch, Ajrakh was traditionally understood as an art. Artisans say that its name means aj rakh (leave it for today). They knew that the slower, more careful their work was, the better the quality.

Ajrakh is just one of many distinct cloths that Khatris historically created. Indian societies comprise many strictly delineated castes or ethnic communities, and each wore a specific dress that clearly identified its members. Within traditions, variations in color and pattern demarcated age, social status, and occasion.

Color was traditionally more than a personal preference. Indigo was a cultural marker (Figure 5). While men of most ethnic communities wore white with no pattern, Muslim Maldhari men, or cattle herders, wore Ajrakh as a poth (lungi, or lower wrap), turban, and shoulder cloth (Figure 6). Maldhari women wore skirts in a progression of colors. Young women wore yellow, middle-aged women wore green, and elders wore indigo. Many Hindus of Kutch believed that it was inauspicious to touch indigo, and women of some Hindu communities wore indigo as a mourning color.

In Vaagad, eastern Kutch, young Kanbi women, who historically migrated from Gujarat, wore indigo-and-white printed saadlos. While Ajrakh and most related cloths are resist printed with a gum arabic and lime substance, the indigo saadlos were batik, printed with wax. Originally, Khatri artisans used a natural wax laboriously extracted from the fruit of the pilu tree (Salvadora persica). As wax was applied hot and adhered to cloth better than gum, larger areas could be printed with patterns, and the cloth could be immersed multiple times to create deeper shades for the background. The limitation was that wax required cold-water dyes. Indigo and kaiyu mud were the only cold-water natural dyes; thus, these were the only two natural dyes used with batik. For blue-and-white cloths, wax was printed on undyed cloth, and it was immersed in indigo. For black-and-red cloths, wax was printed on undyed cloth, and it was dyed black. Then the wax was removed, and the entire cloth was dyed red in a hot madder bath. The result is a deep reddish-black background with red patterns (Figure 7).

Khatris used a similar technique with indigo to create black skirts with red bandhani dots for Ahir women.2 Undyed dublin cloth was tied, dyed in indigo, untied, and dyed red. Red over indigo yielded black. Indigo rather than black was used because the dublin is a thick cloth, and the natural black dye did not penetrate as well as indigo, nor receive enough sunlight to develop the color. Elder Kanbi women also preferred this bluish-black dye, called be rang (two-color), to the reddish-black used by younger Kanbis.

Khatris knew their clients intimately, usually through hereditary relationships, passed down through generations. They bartered their dyed fabrics directly to their users for milk, animals, and grain. They knew when births, marriages, or deaths in their clients’ communities required textiles to mark those occasions. They also knew the tastes of individuals and the allowable variations in styles as those slowly changed over time. They created textiles for specific individuals, with the desire to please them in addition to simply earning. The strong element of personal recognition was mutual. Clients recognized and appreciated the subtle personal signatures of artisans with whom they associated. For generations, artisans did not work simply to earn, but to exchange. When asked how they ensured that the exchange of milk, goats, or grain was equal to that of Ajrakh textiles, Irfanbhai Khatri, a contemporary Ajrakh artisan, replied, “We didn’t.”

In the 1950s, as India began nation building, the government focused on rapid industrialization. Craft was swept into this movement as a complementary means of production that could promise “to help toward the common goal of building India’s path to the future.”3 With the influx of industrially produced goods, traditional clients began to prefer cheaper, newly available mass-produced textiles over handcraft, and artisans were forced to look to distant, unknown markets in urban centers. With industrialization, the concept of design as an entity was also introduced. Designers were actively encouraged to intervene in commercializing craft, both as an inspiration to developing an Indian style as distinct from Western aesthetics, and to help artisans adapt to new markets.

The model for industrial-driven design was to manufacture items faster, cheaper, and in a more standardized way. When artisans began to aspire to new, distant markets, they had to relinquish independent artistic agency and work according to tastes mediated by designers. They also had to look at textiles that had been exchanged in terms of needs and capabilities and revalue them as commodities in a market economy.

Industrialization broke the connection between maker and user, and it changed the methods of making and the character of traditional textiles (Figure 8). Today, hand block-printed fabric is produced in thousands of meters, racing to keep pace with the industrial production that forced artisans to seek distant markets.

As India’s national architects envisioned, consumers in India now equate craft with manufacturing, and they expect it to be cheap. In response, artisans who once created the finest quality textiles now produce what is easiest, fastest, and most cost effective. Forced to calculate the cost of time and materials, they outsource block carving to professional carpenters. In addition, the style of blocks has been altered. Traditional blocks, called char pa ek (four parts to one), in which motifs are created by registering four impressions, have been abandoned for a style called sal type (flush joining), in which the entire motif is on one block. Printing with these blocks is faster, though less perfect—suited for cheap, scaled-up production.

In the way of industrial production, artisans have separated design and execution. They hire cheap manual laborers to print. Khatris with capital employ Khatris with weaker financial status to print and dye, resulting in the stratification of a community that previously had a shared social status. For materials, they choose industrially woven fabrics and synthetic indigo because they are cheaper and easier to use.

Devaluation has made large-scale production an economic necessity, and this has ravaged the fragile arid environment of Kutch. Thousands of liters of water are consumed every day in the Khatri villages Dhamadka and Ajrakhpur. In addition, the debate over natural vs. synthetic indigo plagues artisans struggling to make ends meet. The question is complex, Dr. Ismailbhai Khatri explained. There are natural and synthetic substances, and natural and synthetic processes, making at least four methods possible. Not only is the demand for natural-dyed hand-printed fabric huge; families who once worked with established hereditary clients now compete among themselves for urban markets, a factor that works to minimize the prices of their products. In the twenty-first century, the market remains the root challenge. “They want natural indigo, lot of, and cheap. How is that possible?” Dr. Ismailbhai asks.

In 2005, the author launched a year-long program in design for traditional artisans, operating first as Kala Raksha Vidhaylaya and currently as Somaiya Kala Vidya. As of 2019, thirty-four Khatri Ajrakh and batik artisans had graduated. Of these, two had also taken a year-long business and management graduate course. These artisan designers are rethinking value for their cultural heritage and their art. They are seeking other ways to live within today’s economic and environmental realities.

Conserving water is an immediate environmental concern. Dr. Ismailbhai Khatri, advisor to the education program, worked persistently for years to secure support in developing a system of effluent treatment for Ajrakhpur. Finally, in 2022, the Indian government launched a RS 1.5 crore (about $180,000 by 2024 rates) effluent treatment system in the village. After six months of operation, the project was turned over to the Ajrakhpur Hand Craft Development Organization. Operation is now covered by a monthly fee of RS 2,500 per workshop, and the recycled water can be reused for washing fabric.

Artisan designers are also reevaluating the root issues of scale and relationships to consumers. “These days I have stopped all large orders, and going to pop-up exhibitions,” Khalidbhai Usman Khatri said. “I can get good, smaller orders online. I create a new collection, upload it, and sell it—and the customers don’t bargain for cheaper prices. We need to create unique work to get a good response. When a customer appreciates my work, I am happy” (Figure 9).

Other artisan designers are revaluing the materials they use. Weavers have learned about natural dyeing of yarns. Seeing the magical oxidation of indigo from yellow to blue, Niteshbhai Namori Siju designed a scarf as an ode to indigo.

Shakilbhai Qasam Khatri dreamed of creating batik with a range of natural dyes (Figure 10). There were challenges. Acetic substances such as alum and myrobalan mordants and iron-derivative dyes all reacted to paraffin, making it impossible to remove the wax. In addition, hot dyes would melt the wax. COVID-19 offered him an opportunity. With production suspended, he experimented and developed a range of natural dyes that worked with paraffin wax.

Concerned with both cost and quality, Dr. Ismailbhai Khatri and Azizbhai Alimamad Khatri are growing their own indigo crops. “I want to create completely local and organic fabrics,” Azizbhai said.

Artisan designers are creatively reinventing a more sustainable ecosystem for handcrafted textiles by rethinking their traditions as art rather than commodity, creating in limited quantities, and connecting to distant but discerning markets. If they can succeed, their effort could begin to restore the natural and social environment of Kutch, and to organically combine environment and economics into one whole. It could also restore the value for indigo in Kutch.

Notes

-

Noorjehan Bilgrami, Sindh jo Ajrak (Sindh, Pakistan: Department of Culture and Tourism, 1990), 27. ↩︎

-

Bandhani is a resist-dyeing technique in which small portions of fabric are pinched and tied tightly before the fabric is dyed, resulting in dotted patterns. ↩︎

-

Abigail McGowan, Crafting the Nation in Colonial India (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 199. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Bilgrami 1990

- Bilgrami, Noorjehan. Sindh jo Ajrak. Sindh, Pakistan: Department of Culture and Tourism, 1990.

- McGowan 2009

- McGowan, Abigail. Crafting the Nation in Colonial India. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.