Traditionally, the Mediterranean has been depicted as luminescent white, contrasting with a limpid blue sky and constantly moving turquoise waters. This restricted palette echoes the vision of architectural structures and statues of classical antiquity made of resplendent marble.1 Only in recent times have historians and archeologists begun to investigate color itself, while also bringing to light traces of color on monuments and pieces of art.2 In antiquity, monuments and other constructions were multicolored. They were built with natural material either fully or partially colored with such minerals as malachite or porphyry or veined marbles. Or, they were painted with colors produced with mineral pigments. Objects of daily life such as clothing, fabrics, shoes, furniture, or utensils—and even books—were colored with dyeing and painting, as was the human body. Mastery of coloring was not limited to the Mediterranean world and ancient Greece—the focus of the present essay—but was a general practice all over Europe, as texts from the classical world make clear.

Murex

Explicit information about coloring in the ancient Greek world did not appear until the classical period, in the brief treatise De Coloribus (On Colours), ascribed to, but not authored by, Aristotle (384–322 BCE). Such knowledge of color and coloring techniques may have formed millennia before, as the so-called Blue Period (3200–2700 BCE) of the site of Poliochni on the Greek island of Lemnos indicates.

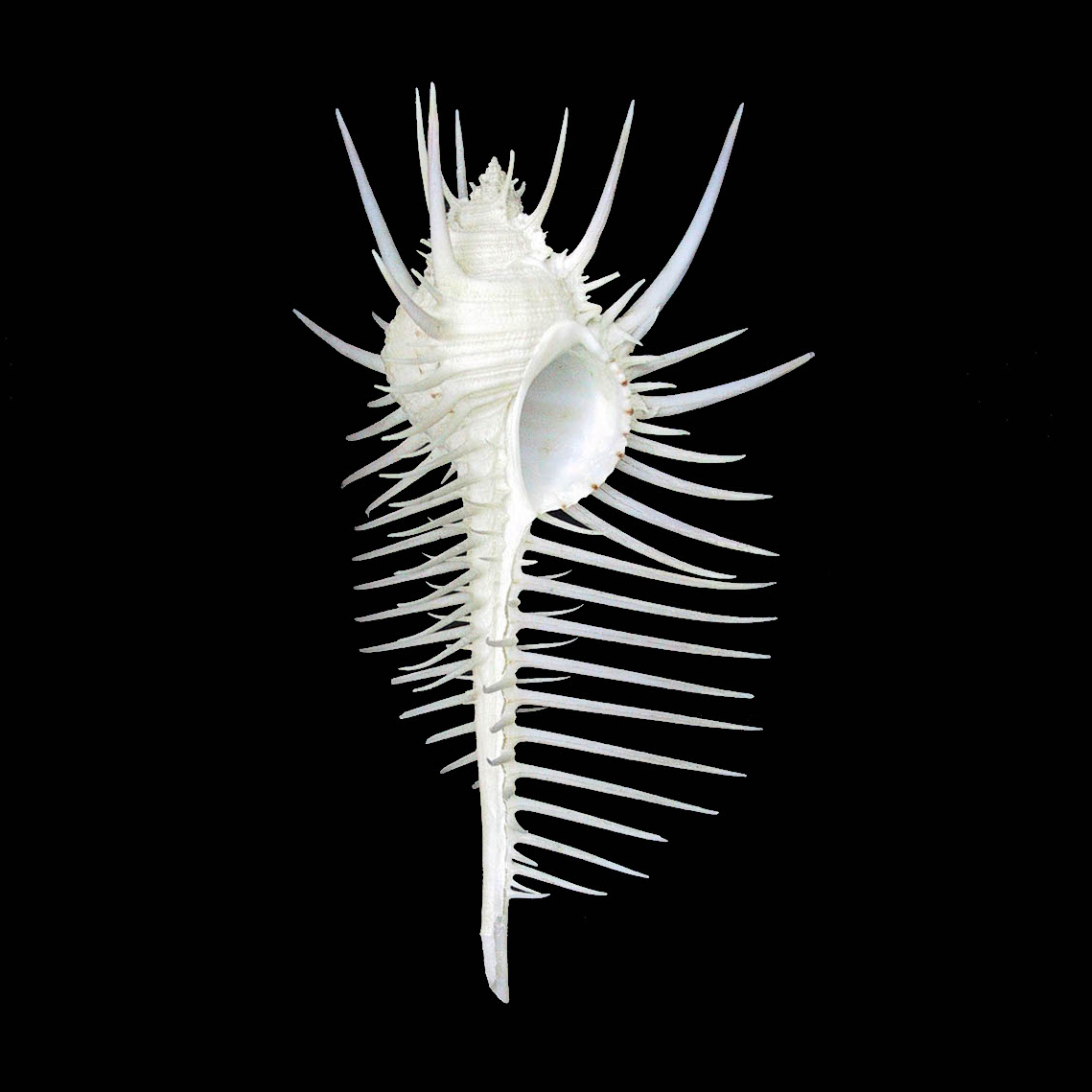

Indigo was part of the chromatic palette of antiquity, with a

great many hues and varieties according to the places, times,

and abilities of the dyers. It was produced from both animal

and plant material, with different techniques depending on the

substance that imparted the color. One such material was

murex, from a genus of sea snails whose secretions are used to

produce indigo (Figure 1). The process of transforming murex

into dye required a mastery of fine chemistry, as the same

tinctorial substance yielded both royal purple and indigo. A

treatise compiled in Aristotle’s school in Athens, the

Lycaeum, demonstrated an exact awareness of the proximity of

the two colors in their making. It tried to resolve

the seeming contradiction of different colors coming from the

same substance:3

The . . . largest number of colours appear when more are mixed with each other. . . . each of the colours becomes fixed by itself, some more quickly and some more slowly, as occurs in dyeing by the murex. For when they have cut this open and drained from it all the moisture, and have poured this out and boiled it in vessels, at first none of the colours is quite obvious in the dye, because as the liquid boils more, and the colours which are still in it get more mixed, each of them exhibits many and varied differences; for there is black and white, and dull, and misty, and finally all becomes purple when the boiling is complete, so that in the mixture none of the other colours is visible by itself.

In his encyclopedia Historia Naturalis (Natural History), Roman naturalist Pliny (23/24–79 CE) tackled the same problem. He considered how different states of the tinctorial matter used to obtain purple from murex produced different colors: “There is another kind [of indigo] that floats on the surface of the pans [i.e., vats] in the purple dye-shops, and this is called the scum [i.e., foam] of purple.”4 A little earlier, he made a similar, though less explicit reference to this source of indigo dyeing: “A black is also produced with dyes from the black florescence which adheres to bronze vats.”5

Although Pliny might not have exactly understood the process, he referred to the foam floating in the vats where murex was boiling. This produced indigo by a process of chemical transformation as the dyeing molecule came into contact with light. This foam was precisely referred to in the first passage above by the expression purpurae spuma, or scum of purple.

In order to dye such material as wool, the tinctorial liquid was reduced to its white, leuco-form and then oxidized to produce a deep blue. However difficult and costly it might have been, this multiphase process was common practice in the Roman world in the first century CE, as the excavations of dyeing vats in Pompeii demonstrate. Roman architect Vitruvius (first century BCE) noted the role of light in transforming the tinctorial matter: “We now turn to purple . . . it does not yield the same colour everywhere, but is modified naturally by the course of the sun. What is collected in Pontus and Gaul is black because these regions are nearest to the north. As we proceed between the north and west, it becomes a leaden blue. What is gathered in the equinoctial regions, east and west, is of a violet colour.”6

Woad

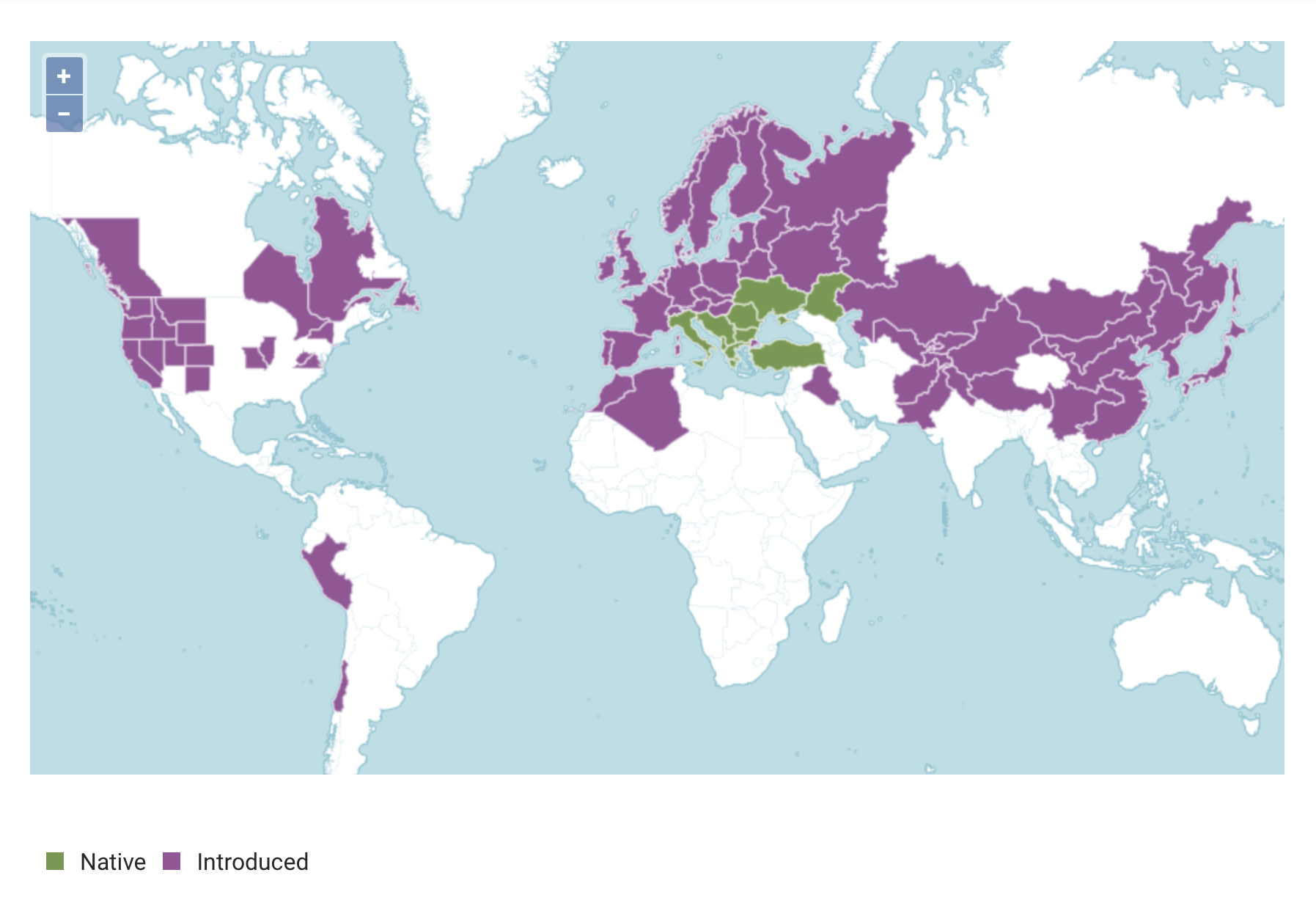

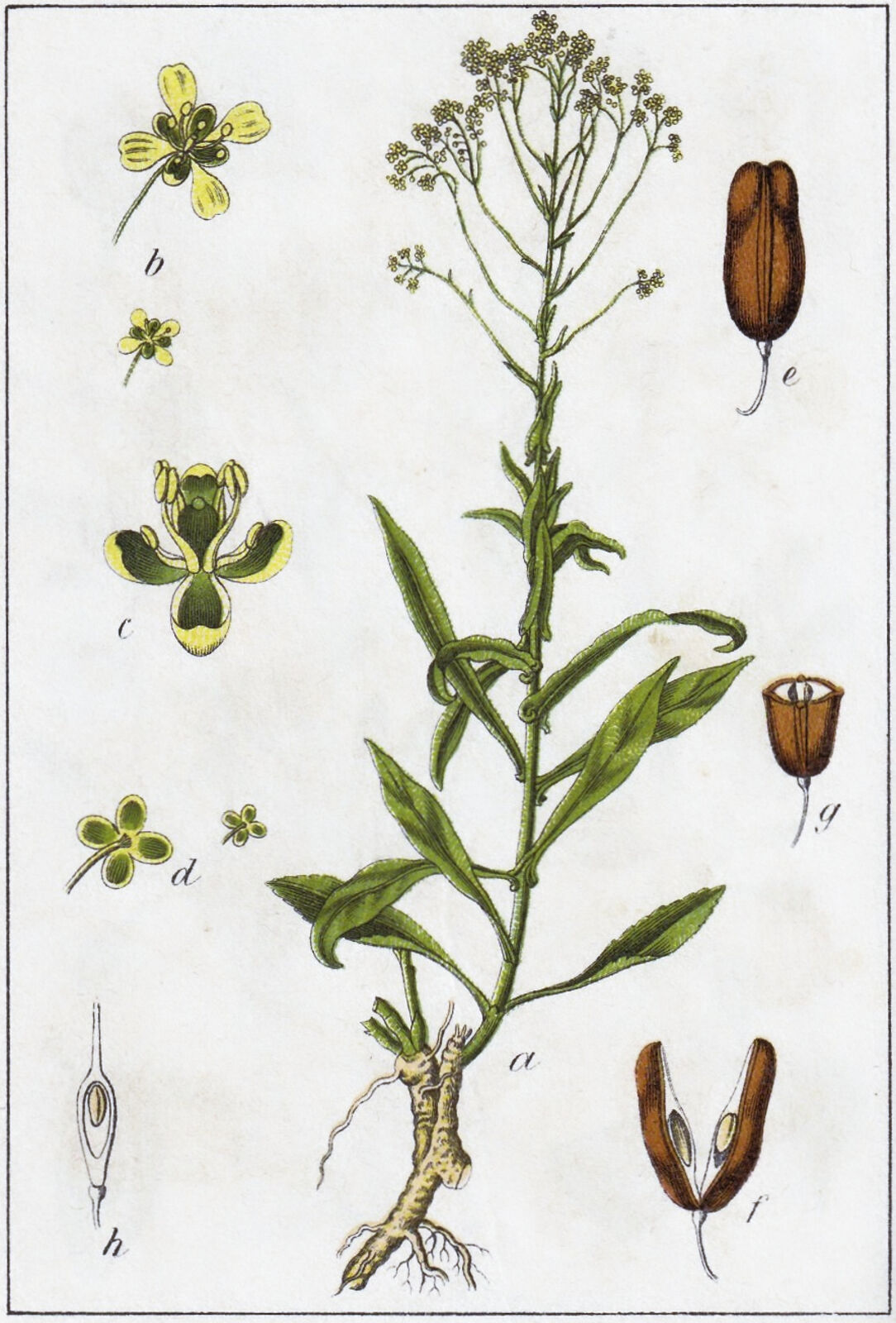

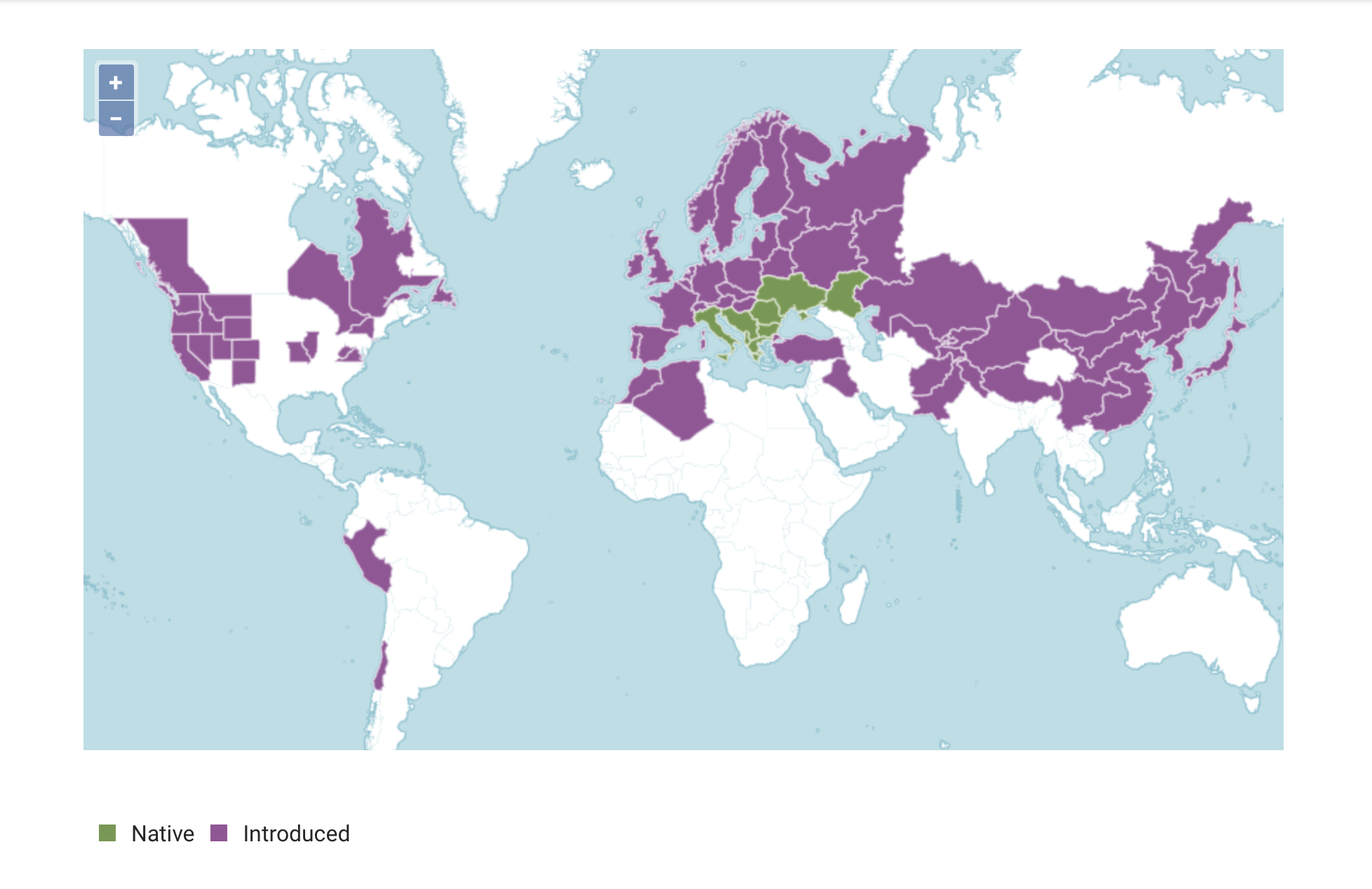

Plant-based dyeing was more manageable. In the ancient world, the species of choice was woad, Isatis tinctoria L., in the family of Brassicaceae (Figure 2). It was native from Italy to South European Russia, including Albania, Greece, former Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, and Ukraine (Figure 3).

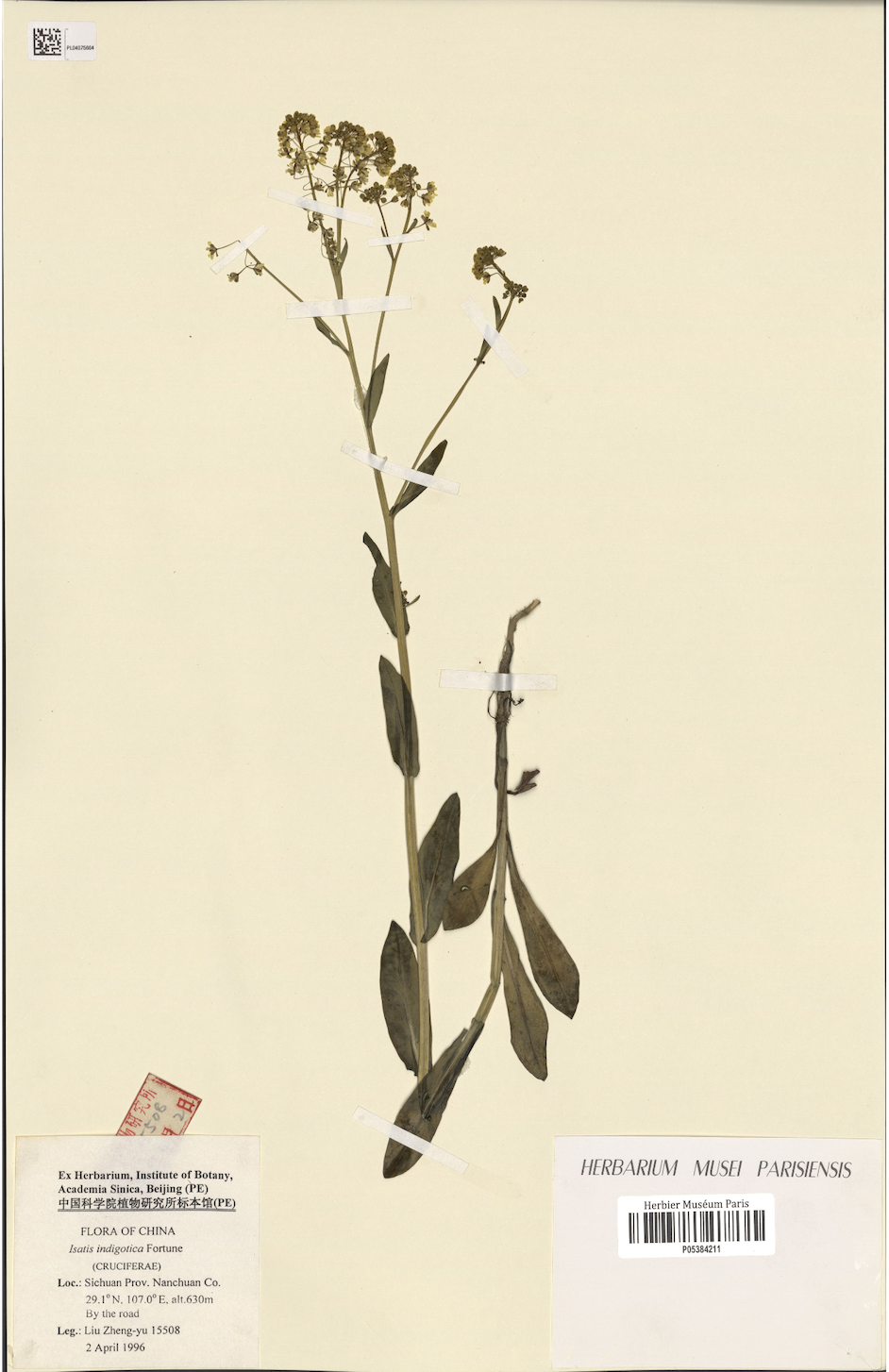

There are several woad species across the world, among which is I. indigotica Fortune ex Lindl. (Figure 4.1), now identified as I. tinctoria subsp. tinctoria (Figure 4.2), which is native to almost the same region (Figure 5).

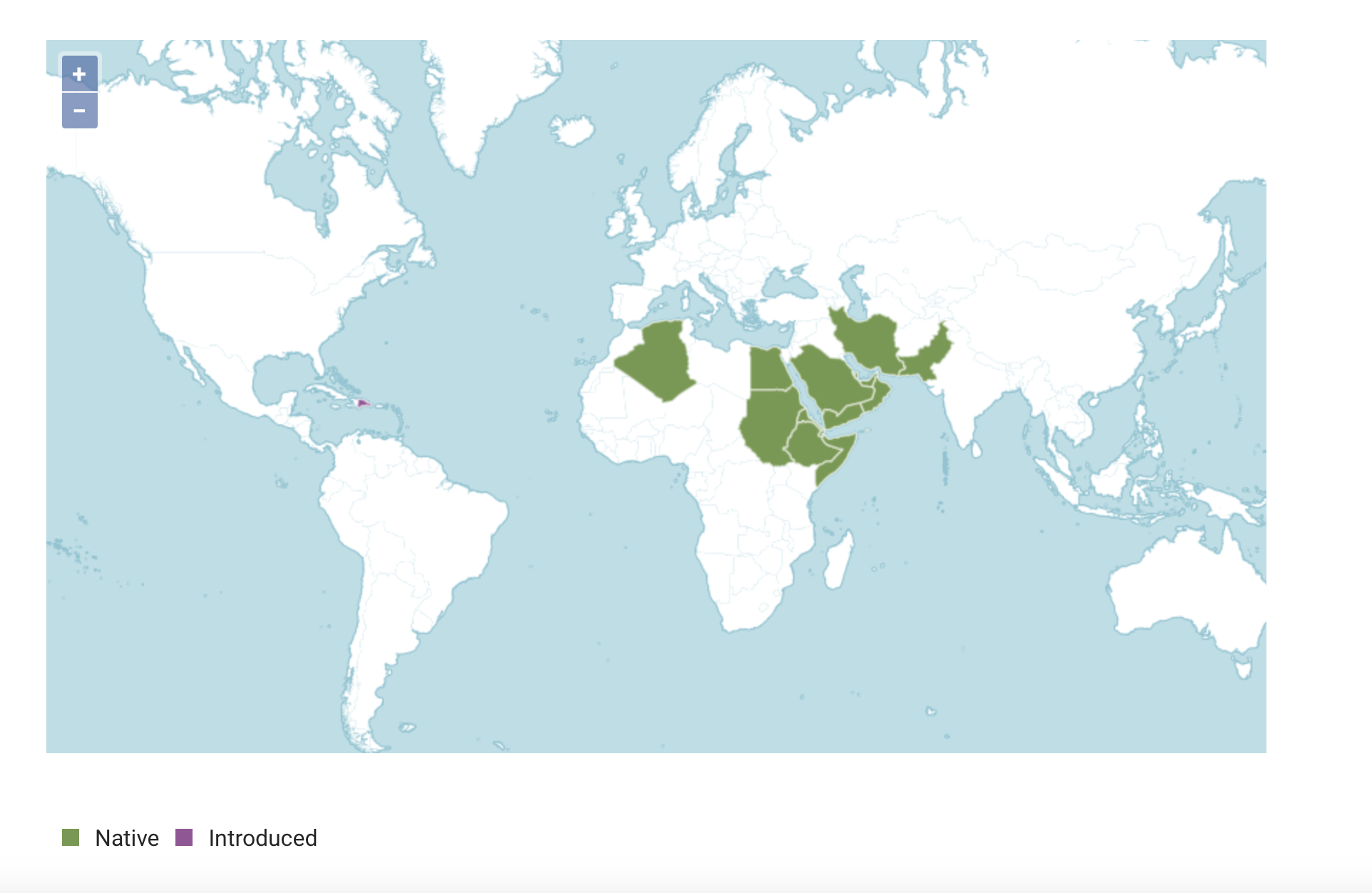

Also of interest here is Indigofera tinctoria Forssk. (I. articulata Gouan) (Figure 6), native to East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Pakistan, and Algeria (Figure 7).

The history of indigo-coloring plants is reported in current scholarship with some confusion, which in fact goes back to Pliny. The plant traditionally identified as Isatis tinctoria L. in modern botanico-historical literature is designated by the term ἰσάτις (isatis) in ancient Greek medico-scientific writings. There, it appears as early as the fifth or fourth century BCE in two treatises of the so-called Corpus Hippocraticum (Hippocratic Corpus), a collection of over sixty treatises attributed to, but not written by, Hippocrates (465–between 375 and 350 BCE). One such treatise is On Wounds (chapter 11),7 of the fifth or fourth century BCE, and the other is Internal Affections (chapter 28),8 of the decade 400–390 BCE, possibly from the medical school at Cnidus, on the continent across from the Hippocratic island of Kos. The plant is not described, but only mentioned for certain uses, detailed below. Isatis does not appear in the Historia Plantarum (Inquiry into Plants) by Theophrastus (371–287 BCE), the pupil and successor of Aristotle in the Lycaeum School.

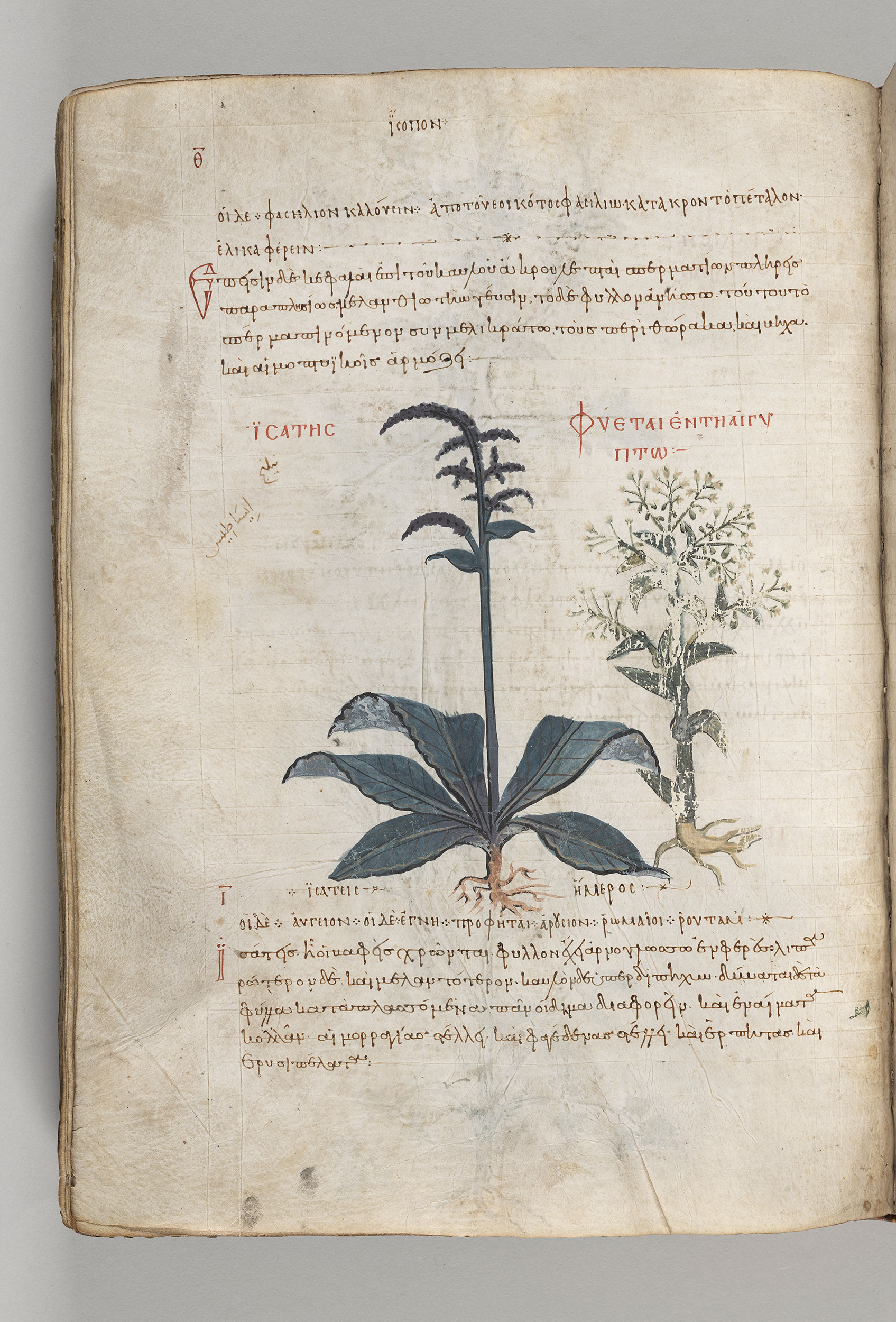

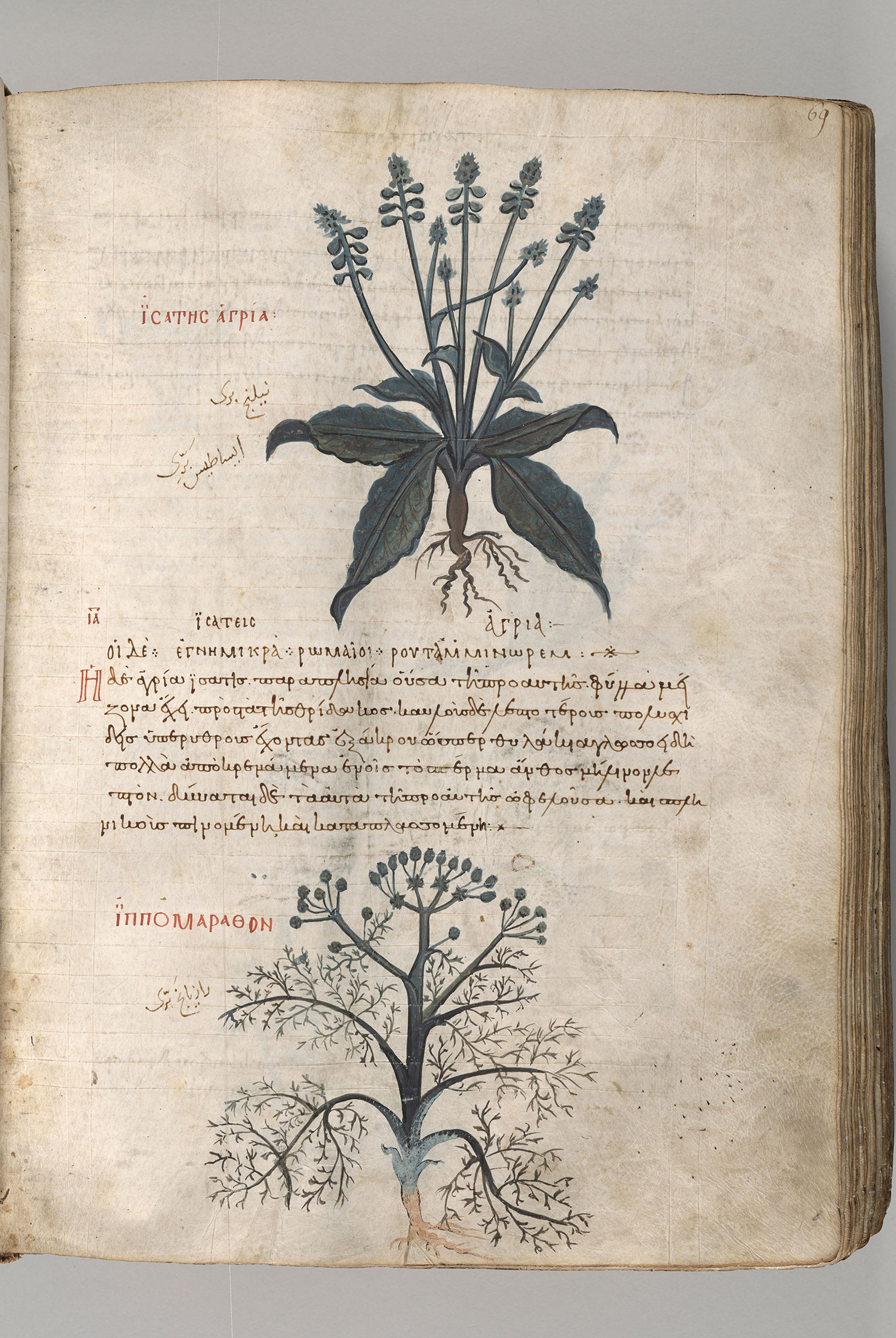

The encyclopedia on materia medica compiled in Greek by Dioscorides (first century CE) and entitled De Materia Medica (On the Natural Products for Medicine) includes the following description:9 “Isatis . . . has a leaf similar to that of plantain, but glossier and of darker colour, and a stem over a cubit long.” This brief description—more of a characterization—seems to result from personal observation of the plant. This could have been by Dioscorides himself or by one of his sources. Isatis is depicted in the illustrated manuscript copies of De Materia Medica with the two species noted in the text (Figures 8–11).10

One element in Dioscorides’ text is significant: the passage cited above specifies that isatis is the plant used by dyers. This information is repeated in the chapter that follows, which is supposedly about the wild species of isatis. There, Dioscorides offers a much more detailed description: “The wild isatis, similar to that which dyers use, has leaves larger [than those of isatis], like those of lettuce, many thin stalks much ramified, reddish, and having at their extremity parts like capsules, lanceolate [shaped like a lance head], in which there is the seed, yellow flowers, thin.” Together with the comparison with plantain (Plantago spp.) (Figure 12), this description of a wild species (particularly the details about the fruit) (Figure 13.1–2) allows us to consider that both species of isatis distinguished by Dioscorides correspond to the species currently identified as Isatis tinctoria L.—that is, woad.

India

Scholars sometimes define indigo as an Indian product and build a narrative on the exchanges between the Indian and Mediterranean worlds. These exchanges started with the expedition to what is now Pakistan by Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) and were subsequently developed by the Roman world, with a peak in the first century CE.

A guide for merchants known as Periplus Maris Erythraei (Circumnavigation of the Red Sea), apparently compiled toward the mid-first century CE, lists products traded in a port named Barbarikon. The place was not identified but was clearly located beyond the limits of the ancient Greek world, in the land of Barbars, as its name indicates. There, goods from India and beyond were actively traded. Among these products was ἰνδικὸν μέλαν (indikon melan, literally, Indian black [product]), for which no other information was provided.11

Similar information appears in two passages of Pliny’s Natural History. The first one comes after a discussion of dark purple: “There is also an Indian [color], imported from India, the composition of which I have not yet discovered.”12 Although this color is traditionally considered to be black, it was in fact the tinctorial substance from which indigo was obtained, which was traded in its dry form.

The second relevant passage by Pliny comes after a discussion of purple and its production in Italy: “Of next greatest importance after this [purple, purpura] is indigo [indicum], a product of India, being a slime that adheres to the scum [i.e., foam (spuma)] upon reeds. When it is sifted out it is black, but in dilution it yields a marvellous mixture of purple and blue.”13 This Indian indigo was clearly a dry substance, of a dark color, close to black. Only when diluted did it reveal its real color.

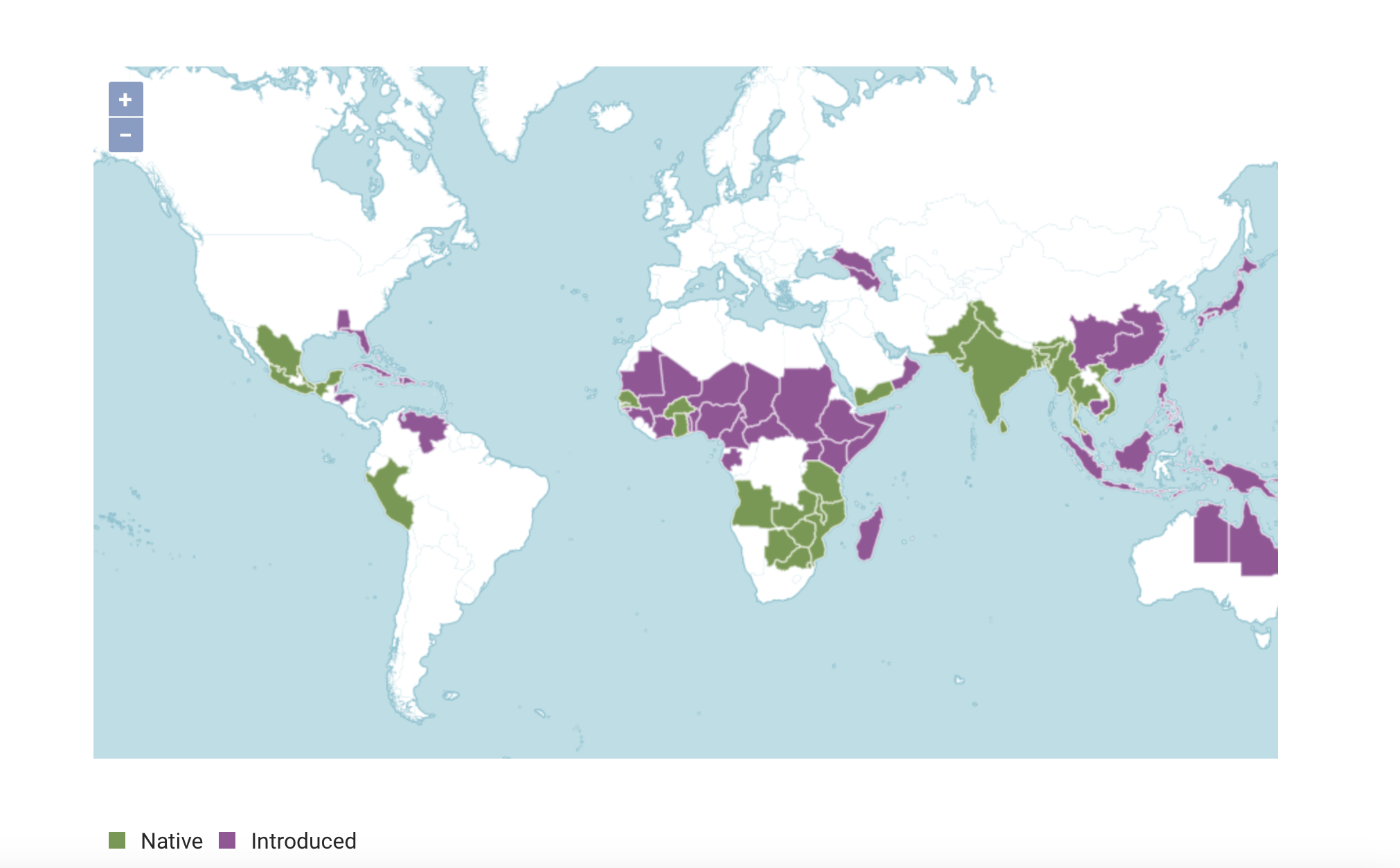

These references suggest that a tinctorial matter of unknown nature (even though Pliny speculated, possibly based on hearsay, that it was slime on the foam attached to reeds) was identified as indikon. This was because of the origin of its trade, not necessarily the region where it was produced, according to a process of identification of traded substances that was common in antiquity. This substance was among the products freighted by the ships sailing between India and the Red Sea and further afar in both directions, to the Mediterranean and Rome and beyond India, possibly up to China. Black and dry, it produced a deep blue-purple color when diluted. This tinctorial matter is probably better identified as indigo cakes, made of the paste obtained by the maceration and fermentation of plants of the type of Isatis tinctoria L. One such plant was Indigofera tinctoria L. (Figure 14), native to a region ranging from Pakistan to Vietnam that also included the Arabian Peninsula, with native populations in Yemen, Africa (East and West), and limited regions of Central and South America (Figure 15).

Because its name was coined by the origin of its trade—indikon referring to India—this tinctorial matter and the color it produced have been incorrectly identified as a typically Indian product and color. The resulting color has been called indigo ever since, even when produced from murex.

Interestingly, the high cost of indigo production from murex led to substitutes, one of which was described by Vitruvius:14 “because of the scarcity of indigo [from murex] they [the painters] make a dye of chalk from Selinus, or from broken beads, along with woad [which the Greeks call isatis], and obtain a substitute for indigo.”

Whereas murex-based indigo might not have been widely used because of the cost of its production, as the substitution above further stresses, plant-based indigo was much more diffused for the coloring of fabrics, shoes, and a variety of daily objects.

Medicine, Tattoos, Body Painting

Medical uses for indigo might have come later, based on the evidence found in ancient texts. Although isatis (Isatis tinctoria L.) is listed in the Hippocratic Corpus, it does not appear in the earliest treatises and is mentioned in only two formulae for medicines. One such mention is in On Wounds, which says to treat skin diseases with a poultice. The other is in Internal Affections, which advises applying isatis externally to alleviate the pain of diarrhea and more serious intestinal conditions.

The uses reported in the first century CE by Dioscorides, in De Materia Medica, are few, suggesting that isatis had only recently been introduced into the therapeutic arsenal. The leaves of the first species are recommended for external uses: to treat swelling, close bleeding wounds, stop hemorrhages, and eliminate skin diseases like those mentioned in On Wounds. The wild species has the same indications, plus the treatment of spleen conditions with a poultice. Pliny wrote little about medical uses of the plant, except for a passage on the species of lettuce. Probably because the leaves of isatis are described as being similar to those of lettuce, as in Dioscorides, he did consider isatis to be a species of lettuce,15 and he mentioned that it was used externally for the treatment of wounds.

This paucity of indications, all in external use, even for the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases, hints at a recent inclusion in the range of materia medica that contrasts with the much more common use of indigo in coloring. This difference is further stressed by Pliny in his reference to tattooing and cosmetic uses:16

Now I notice that some foreign peoples use certain plants on their persons both to make themselves more handsome and also to keep up traditional custom. At any rate among barbarian tribes the women stain the face, using, some one plant and some another; and the men too among the Daci and the Sarmatae tattoo their own bodies. In Gaul there is a plant like the plantain, called glastum; with it the wives of the Britons, and their daughters-in-law, stain all the body, and at certain religious ceremonies march along naked, with a colour resembling that of Ethiopians.

Glastum is the Latin for isatis, the leaves of which were compared in Dioscorides to those of plantain, as we have seen. The whole passage is typical of Pliny’s defense and illustration of traditional Roman values by ascribing face and body painting to barbarians in a moralizing way. Interestingly, the practice is first attributed to women as a cosmetic aimed at seduction. It is then linked to men of tribes beyond the Danube, which marked the limits of the Roman Empire, or further, in the steppes north of the Caucasus. The practice is also described as being typical of populations within the empire, in Gaul, with uses that combine nudity, religious ritual, and imitation of blackness in a very non-Roman amalgam.

Indigo proved to be important well into the Middle Ages. In the Arab world, substantial notice was devoted to it by ibn Sina (980–1037). Known in the West as Avicenna, he wrote about indigo in the Qanun (Canon), designating it hot/dry and describing its use for cosmetics and for the treatment of swelling, wounds, and ulcers, as well as respiratory and digestive conditions. Indigo appears in the so-called Old English Herbal, possibly of the eleventh century, but is limited to the treatment of snake bites and called ad serpentis morsum on this basis. Many formulae for producing blue and indigo appear in the late fifteenth-century Trattato Universale dei Colori (Universal Treatise on Color-Making); in fact, nine of the twenty-two formulae for blue-making incorporate indigo made with woad.

Conclusion

The use of indigo in antiquity demonstrates not only a mastery of the precise chemistry necessary to produce indigo from murex but also a long tradition of dyeing with plants, particularly Isatis tinctoria L. For both, modern chemistry has since elucidated the mechanisms, demonstrating how effective such techniques were, even though ancient artisans did not have the exact knowledge and understanding of the actual processes at work. At the same time, the ancient Greeks had scant knowledge of the health benefits to be obtained from indigo. Whereas research has since established the positive effects on health generated by blue, much more needs to be done to ascertain its therapeutic properties.

Notes

-

Though contradicted by archaeological remains from Knossos polychrome frescoes (2000–1500 BCE) to Pompeian red (first century CE), this monochromatic idea of the past was reasserted and theorized in eighteenth-century archaeology by the influential German art historian and archeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768). ↩︎

-

It should be noted that German-born French architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff (1792–1867) published his work De l’Architecture polychrome chez les grecs (Polychrome architecture by the Greeks) as early as 1830. ↩︎

-

Aristotle, On Colours 795b10–22, ed. and trans. Walter Stanley Hett, Loeb Classical Library [hereafter LCL] 307 (London: William Heinemann, 1936), 26–27. ↩︎

-

Pliny, Natural History, book 35, chap. 46, ed. and trans. Harris Rackham, LCL 394 (Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1961), 294–95. Italics added. ↩︎

-

Pliny, Natural History, book 35, chap. 43, ed. and trans. Rackham, 292–93. ↩︎

-

Vitruvius, On Architecture, book 7, chap. 13, sections 1–2, ed. and trans. Frank Granger, LCL 280 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1934), 126–27. ↩︎

-

Hippocrates, Ulcers (On Wounds), chap. 11, ed. and trans. Paul Potter, LCL 482 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995), 348–51. ↩︎

-

Hippocrates, Internal Affections, chap. 28, ed. and trans. Potter, LCL 473 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988), 172–75. ↩︎

-

Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, book 2, chap. 184, ed. Max Wellmann, 3 vols. (Berlin: Weidman, 1907–14), 1:253–54. A cubit is approximately 18 inches (46 cm). ↩︎

-

Dioscorides’ Roman contemporary Pliny, who often offered similar information, as he probably consulted the same reference works, did not provide any description of the plant, contrary to what he did in so many other cases. ↩︎

-

The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary 39, ed. and trans. Lionel Casson (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989), 74–75 for the Greek text and the English translation; 194–95 for a commentary. ↩︎

-

Pliny, Natural History, book 35, chap. 43, ed. and trans. Rackham, 292–93. ↩︎

-

Pliny, Natural History, book 35, chap. 46, ed. and trans. Rackham, 294–95. ↩︎

-

Vitruvius, On Architecture, book 7, chap. 14, section 2, ed. and trans. Granger, 128–29. Selinus refers to Selinunte, in Sicily. ↩︎

-

Pliny, Natural History, book 20, chaps. 58–59, ed. and trans. William H. S. Jones, LCL 392 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1951), 34–37. ↩︎

-

Pliny*, Natural History*, book 22, chap. 2, ed. and trans. Jones, 294–95. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Abu-Asab 2020

- Abu-Asab, Mones, trans. Avicenna’s Single Drugs: The Second Book of the Canon of Medicine. Bethesda, Md.: the author, 2020.

- Aristotle 1936

- Aristotle. On Colours. Edited and translated by Walter Stanley Hett. Loeb Classical Library 307, 1–45. London: William Heinemann, 1936.

- Casson 1989

- Casson, Lionel, ed. and trans. The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Dioscorides 1907–14

- Dioscorides. De Materia Medica. Edited by Max Wellmann, 3 vols. Berlin: Weidman, 1907–14.

- Hippocrates 1988

- Hippocrates. Internal Affections. Edited and translated by Paul Potter. Loeb Classical Library 473, 70–255. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988.

- Hippocrates 1995

- Hippocrates. Ulcers (On Wounds). Edited and translated by Paul Potter. Loeb Classical Library 482, 335–75. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Niles and D’Aronco 2023

- Niles, John D., and Maria A. D’Aronco, ed. and trans. Medical Writings from Early Medieval England, vol. 1, The Old English Herbal, Lacnunga, and Other Texts. Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library 81. Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, 2023.

- Pliny 1951

- Pliny. Natural History, vol. 6, Books 20–23. Edited and translated by William H. S. Jones. Loeb Classical Library 392. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1951.

- Pliny 1961

- Pliny. Natural History, vol. 9, Books 33–35. Edited and translated by Harris Rackham. Loeb Classical Library 394. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961.

- Vitruvius 1934

- Vitruvius. On Architecture, vol. 2, Books 6–10. Edited and translated by Frank Granger. Loeb Classical Library 280. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1934.