In the intricate and vibrant landscape of Korean culture and philosophy, the significance of indigo unfurls, revealing a timeless narrative. As I explore the tapestry of my heritage, the profound connection between my homeland and the captivating color blue becomes apparent. In the following essay, I discuss the importance of blue to Koreans, focusing on two contemporary indigo-dyeing practitioners who are working to reclaim and restore this timeless art.

Blue, a central hue in what is known as Five Color Theory, plays a pivotal role in the cultural fabric of Korea. Obangsaek 오방색, the classical Korean color spectrum, comprises white, black, green/blue, red, and yellow—a cultural mosaic embedded in everyday life. These colors resonate not only in textiles but also in architecture, music, and even cuisine. The colors connect to the various elements that shape the universe. The hues link to the cardinal directions and to philosophical concepts, adding layers of meaning.

Green/blue, or cheong 청, symbolizes wood, east, and youth. Intriguingly, green is sometimes considered a variant of blue, and both colors are described with the same term. This idea is expressed in the ancient idiom cheong chul a-ram 청출어람. This suggests that blue originates from the indigo plant but transforms into a shade even bluer than itself—like the Western saying, “The pupil has become the master.”

As fall graces Korea, the sky transforms into a clear blue canvas, described as jjokbitaneul 쪽빛하늘—indigo sky. However, this indigo is not the deep midnight blue typically associated with the color. I believe that my ancestors appreciated a broad range of indigo, admiring not only its dark tones but also its light shades. In natural indigo dye processes, a variety of shades emerge, particularly the alluring jade-to-turquoise shades created from fresh indigo leaves. These are reminiscent of the elegant Korean cheong-ja, known as celadon.

Embracing this season-sensitive process, which happens in summer, I have focused on the jade-to-turquoise shades made from Polygonum tinctorium (also known as Persicaria tinctoria). This prominent species is cultivated and used across East Asia, including China, Japan, and Korea. The indigo plant, jjok 쪽, yields its extracted pigment in paste form, known as niram 니람. Jjok, an annual, disappeared from the Korean Peninsula right after the Korean War in the 1950s. The vivid turquoise shade it produces not only captivates with its beauty but also symbolizes a deep cultural connection to nature. It resonates with ancient traditions of respect, coexistence, and the Buddhist vision of reincarnation, the backbone of the culture in which I grew up.

Over the past five years in Baltimore, I have been cultivating jjok and extracting its blue pigment by using the fresh indigo leaf dye-making process. Unlike setting up a fermentation vat, making dye from fresh leaves is simple, requiring few steps and tools. By simply harvesting indigo plants, rinsing them thoroughly, and agitating the leaves in water to extract the blue pigment, one can create a cold indigo “juice.” This process relies on the weather and the condition of the indigo leaves. Precise timing is crucial to achieving the exact shade that is desired.

These steps must unfold rapidly, typically within fifteen to twenty minutes, to yield the most pristine turquoise shades. The color is not under our control; rather, it relies on a collaboration between nature and indigo plants to achieve a certain outcome. This elegant process has truly opened my eyes to the ancestral wisdom of harmonizing with nature, a forgotten mindset in today’s hectic society.

Niram making is another process that depends on natural cycles and can only be done in the summertime, based on the geography of Naju, South Korea, and where I live. This paste is produced through a water extraction process: soaking indigo leaves to collect their blue pigment. The summer heat aids fermentation, which takes one to two weeks. In this collaboration with nature, other natural substances are added to the solution, including burnt seashell powder to augment alkaline levels, a small amount of makgeolli 막걸리 (Korean rice wine), and ashes from beanstalks and wood. Particles of indigo settle to the bottom of the vat, and the dark paste that results is then dried.

Equipped with this hands-on knowledge of pigment-making processes, I returned to Korea in 2022 to learn more. This once-in-a-lifetime experience reacquainted me with the range of blue hues, from light turquoise to dark indigo. While visiting Seoul, Naju 나주, and Icheon, I had the privilege of meeting two influential figures in the indigo-dyeing industry: indigo master Jung Gwan-chae 정관채, in Naju, and Sou Jou Jang 장수주, founder of Kindigo 킨디고 Studio in Icheon. I feel grateful and humbled to have this platform to share a glimpse of Korean indigo and draw inspiration through my own voice.

Naju, nestled in South Jeolla Province, boasts a warm climate and optimal conditions for indigo, cotton, and silkworms. The Natural Dyeing Culture Center, a hub for local textile artisans, has played a crucial role in educating craftspeople and preserving textile traditions. My connection with the organization, dating back to 2017, led me to meet Jung Gwan-chae, Korea’s designated Living National Treasure for the process of indigo fabric dyeing. His center, which opened to the public in 2009, provides a glimpse into the rich history of indigo dyeing through artifacts not commonly found in U.S. museums (Figure 1).

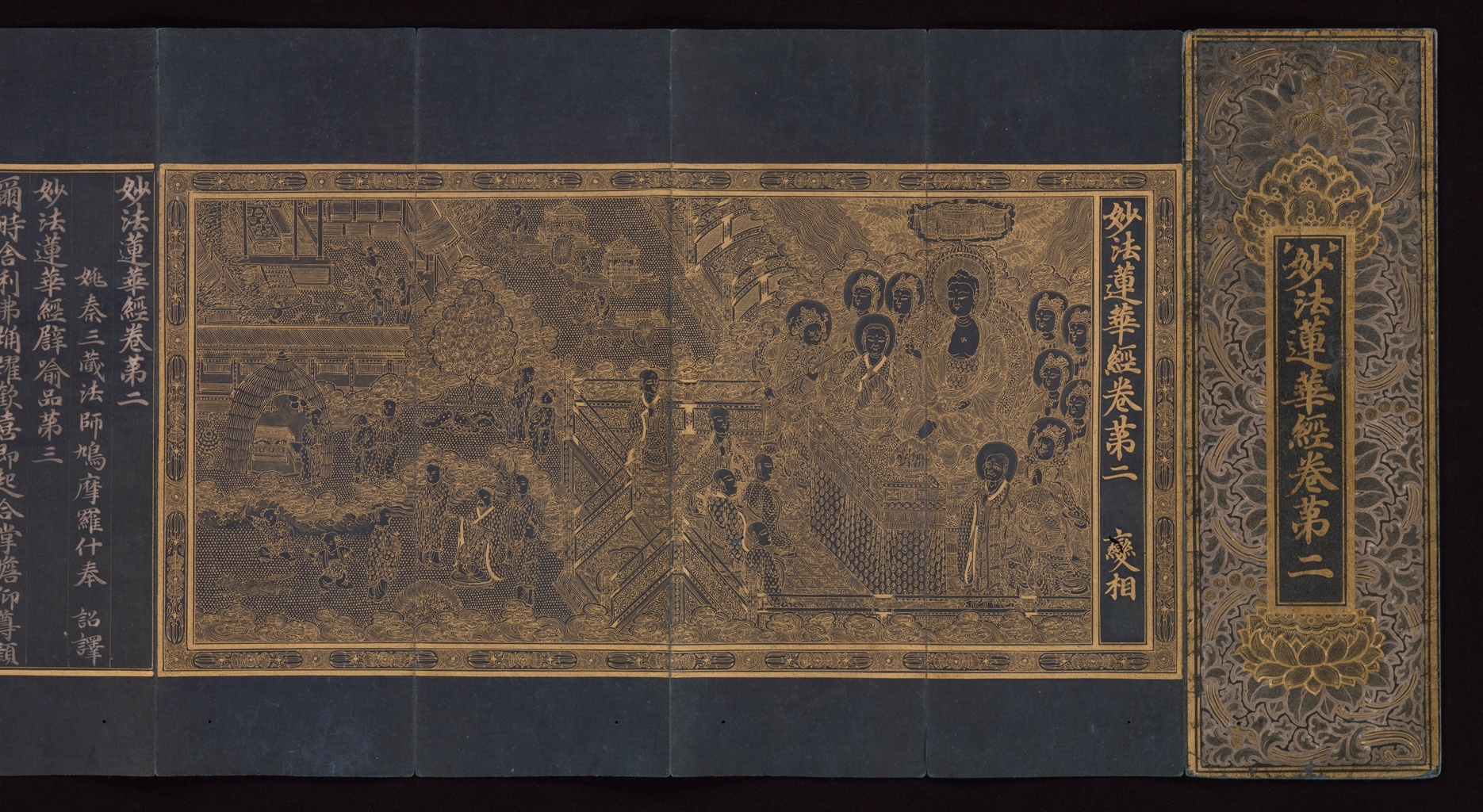

Before my visit, the only historical indigo-related Korean artifact I had come across in the United States was an illustrated Buddhist manuscript of the Lotus Sutra from around 1340 (Figure 2). This sumptuous object from The Metropolitan Museum of Art is reproduced in Indigo: Egyptian Mummies to Blue Jeans, by Jenny Balfour-Paul. Unfortunately, I have not had the opportunity to view the manuscript in person. I did examine a similar indigo-dyed manuscript from Japan in The Met’s collection of Asian art in 2016 while doing research for my Indigo Shade Map, an ongoing project on indigo dyes, cultural stories, and sustainability.

While I was in Naju, Master Jung graciously guided me through each artifact in his collection, explaining the rich history and living tradition associated with each item. He delved into how people had used these objects, explaining why they had specifically chosen indigo-dyed cloth to create certain pieces.

For instance, in the Naju region, there exists a wedding tradition in which the bride’s mother and female family members craft a blanket as a heartfelt gift. They choose indigo-dyed fabric for the insert, due to its well-known antiseptic and antibacterial properties, good for individuals with sensitive skin. This medicinal fabric has also been used for infants’ shirts and blankets. Additionally, during epidemics, people would boil indigo-dyed fabric in water as a precautionary measure to safeguard against illness.

Amid these captivating artifacts and inspiring tales in Naju, a specific item captured my attention. This recently made object, yoon hwae mae 윤회매 (輪迴梅), consists of life-size plum blossom flowers, meticulously crafted from colored beeswax (Figure 3).

These flowers, when delicately attached to tree branches, remarkably resemble plum blossoms freshly cut in the early morning. This stunning arrangement graces a distinguished vessel of classic white Korean porcelain. The plum blossoms’ captivating shade of blue is achieved by infusing powdered niram (indigo pigment) in beeswax. This technique represents a variety of plum tree called cheongmaehwa 청매화, known for the subtle blue tint of its petals.

The origin of yoon hwae mae is as captivating as its visual appeal. The term yoon hwae refers to the karmic cycle, while mae refers to a plum tree. But how do these beeswax blossoms symbolize reincarnation? The technique and philosophy behind crafting them was developed by scholar Lee Deok-moo 李德懋 (1741–1793) during the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897).

For Lee, the beeswax used in honey production seemed to come from flowers, including plum blossoms. This set in motion a cycle referred to as the “reincarnation of the flower.” It began with the transformation of the nectar and pollen of the plum blossom into honey and beeswax. Inside the honeycomb, this change continued, resulting in the reincarnation of the flower. This cycle suggested an interconnectedness among plum blossoms, beeswax, and honey, each seemingly forgetting its previous form.

Lee wrote that, before turning into a flower again, the substance existed as beeswax rather than in its floral form. The link to the plum blossom endured because the beeswax carried the essence of the flower. The blue-tinted yoon hwae mae I saw in the Naju collection was made by local artist and researcher Kim Chang-deok, also known as Da-eum 다음. He has revived the beeswax plum blossom-making process, which had been discontinued for many years.

As I moved on to the countryside near Icheon, south of Seoul, I explored Kindigo’s lush indigo fields, cultivated through organic farming. They provided me with profound insights into the significance of this eco-friendly process, deeply rooted in Korean culture (Figure 4). This practice holds great importance in terms of passing down traditions to younger generations. For me, the everyday objects transformed by fermented indigo dye left a lasting impression, evoking the revitalization of ancestral wisdom.

Kindigo’s products include indigo-dyed socks and undergarments that maximize the functionality of the fabric. The studio also offers do-it-yourself dye kits for hobbyists and handwoven rugs crafted from recycled indigo-dyed scraps. Kindigo’s contemporary indigo expressions showcase the perfect blend of simplicity and humility, yet they have sparked a trend among the younger generation. Together, they bridge cultures, living traditions, and innovation.

As I reflect on my journey through Naju and Icheon, I have come to realize that indigo is more than just a pigment: it is a testament to the resilience of cultural heritage. From the vibrant turquoise hues of fresh indigo leaves in Baltimore to the time-honored artifacts in Naju and the contemporary expressions in Icheon, indigo continues to resonate with Korean identity. It is also perpetually evolving, echoing the dynamic spirit of a culture deeply rooted in the essence of cheong—the eternal cycle of youth and spring.

The exploration of Korean indigo is an ongoing adventure, and I feel fortunate to share it with many others. While Korean foods and pop culture now enjoy widespread recognition globally, the rich traditions of Korean indigo and textiles are just beginning to reach a broader audience. The exhibition Blue Gold: The Art and Science of Indigo at Mingei International Museum marks a significant step in this revival of Korean indigo. I hope this moment provides inspiration and helps audiences grasp the profound journey of indigo, appreciating the precious culture and wisdom of Korean textiles and philosophy.

Header Image: Indigo swirl from Indigo Shade Map ,photograph by Rosa Sung Ji Chang, image courtesy of the artist.