Indigo is perhaps the earliest type of dye used by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. At least 6,200 years ago, it was used as a source of blue at the preceramic site of Huaca Prieta in Peru.1 Various species of indigo-producing plants were used in the Americas, including Baptisia and Indigofera.2 These plants provided not only dye but also medicine, as discussed below. Dyeing with indigo may have had spiritual significance, as the transformative nature of the process may have been linked to rituals and cosmological beliefs.

This essay surveys the use of indigo dye in the Americas prior to the introduction of people, plants, and practices from Europe, Asia, and Africa. It begins with what is now eastern North America and works its way through the U.S. Southwest, Mesoamerica, and the central Andes. The essay ends with a series of recent experiments that were carried out to better understand the earliest indigo practices found at Huaca Prieta.

Eastern, Midwestern, and Northwest North America

Indigenous peoples deeply understood the plants and natural resources available to them, and they found creative ways to incorporate these resources into their daily lives. Direct evidence for the use of indigo in North America prior to the fifteenth century, however, is scant. Textile specialist Penelope Drooker notes that blue in pliable fabrics and basketry from southeastern North America is quite uncommon compared with red, yellow, black, and natural/white colors.3

The rarity of blue might be a result of having few samples to consider, as fabrics do not survive well in humid conditions. Fiber and other perishable materials have been recovered from mound burials at Mississippian (ca. 900–1700 CE) and Hopewell/Adena (ca. 800 BCE–500 CE) ceremonial centers, but none of the studies of Mississippian fabrics have reported blue pigments.4 In a study of fabric fragments from Seip Mound, a Hopewell site in Ohio, Christel Baldia encountered green, blue (in charred fragments), and turquoise pigments.5 Her analyses indicate that the green yarns were consistent with having organic dyes. The turquoise coloration had blue granules consistent with mineral pigments, and the blue seemed to be an iron-containing clay such as glauconite.6 Interestingly, iron clays were also used as a blue color in some nineteenth-century painted bison hides (Figure 1).

Drooker notes that probably the earliest analytically verified evidence of indigo use in an eastern Native American context is from a Mashpee Wampanoag burial ground on Cape Cod dating to the last half of the eighteenth century. She believes, however, that European-made, indigo-dyed fabrics were in use by Native Americans long before then.7

Despite this lack of direct evidence for the use of indigo as a dye, Native North Americans certainly had access to indigo-producing plants. Baldia notes that there are several native North American plants of the genus Indigofera, including I. miniata Ortega (coastal indigo) and I. caroliniana P. Mill (Carolina indigo).8 Other species native to eastern North America that reportedly produce indigo include Amorpha fruticosa (false indigo or false indigo bush) and various species of Baptisia, which grows wild in most of the contiguous United States, southeastern Canada, and northern Mexico.9 Expert dyers John and Margaret Cannon state that B. tinctoria (false indigo or wild indigo) contains indican, a precursor of indigo dye.10

While there is no archaeological evidence for the use of Baptisia spp. as a source of indigo blue, both B. tinctoria and B. australis (blue wild indigo) are mentioned in historical records as a source of blue dye used by the Cherokee.11 Considering that immigrants from Europe would not have been familiar with these plants, it is likely that Native Americans were using Baptisia species prior to contact. These technologies may have also been practiced by the Indigenous peoples of the Plains and the Pacific Northwest, about whose dyeing practices we know little.

Southwestern North America

In the Southwest, evidence from archaeological textiles indicates that Indigenous people there used indigo-dyed yarns in their weaving. For example, the people south of the Mogollon Rim (for example, central and southern Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, and northern Mexico) used indigo-dyed yarns in small quantities.12 At least one Mogollon-Mimbres cotton fragment from Cliff Valley (ca. 1400 CE) “revealed the presence of indigo,”13 and indigo is likely present in a cotton textile with blue fibers from Bear Creek Cave.14 Evidence from the Chihuahua region of northern Mexico also suggests that indigo was used to dye textiles there.15 Laurie Webster has studied a fragment of tie-dyed cloth from Casa Grande with a dot-in-a-square motif whose blue ground was likely achieved with indigo.16

According to Webster, most of the documented indigo from the Southwest appears sparingly, such as small areas of decoration or individual yarns attached to an object (Figure 2).17 Further, indigo-producing plants are not native to the Southwest, which raises a question regarding the source of the indigo. Webster suggests that it was traded from areas where indigo grows in Mexico.18 If so, did it travel as a living plant, as pre-dyed yarns, or as dried cake, as it is sold today and historically traded with the Pueblos and Navajos?19

Perhaps the people of the Southwest imported yarns already dyed with indigo. This seems consistent with the archaeological evidence and with practices in the ancient Andes, where most camelid-hair yarns seem to have been dyed and then traded.20 That being said, Webster has more recently considered the possibility that indigo may have been grown in riparian regions using seeds imported from Mexico.21

Indigo in Mesoamerica

The use of indigo by the native peoples of Mesoamerica prior to contact with Europeans was a well-established tradition. Indigo played a crucial role in these vibrant and sophisticated cultures, which include present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. Among the species of indigo-producing plants available were I. suffruticosa Miller (also known as I. añil), I. guatemalensis,22 and possibly Koanophyllon albicaule.23

The knowledge of indigo cultivation and dyeing techniques played a vital role in the cultural and economic life of Mesoamerican societies. For example, Patricia Anawalt believes that xiuhtlalpilli—the Mexica emperors’ high-status, tie-dyed capes with motifs like those from Casa Grande and Don Bonfilio Cave in the Tehuacan valley of Puebla, Mexico—were dyed with indigo blue. This is based on depictions of xiuhtlalpilli in surviving codices from the Late Postclassic era (1200–1521 CE).24

The Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, a Spanish chronicler, observed in the mid-sixteenth century that Mexica women dyed their hair with xiuhquilitl25 (i.e., I. suffruticosa) “to make their hair shine with a sort of purple hue.”26 He also noted: “There is a plant in the hot lands that is called xiuhquilitl. They pound this herb, squeeze out the juice, and pour it into some cups. There it dries up or sets. This indigo color is used to achieve a bright dark-blue dye. It is a cherished color.”27

While codices and descriptions from Spanish chroniclers make it clear that indigo was an important source of blue to Mesoamerican people, physical evidence is rare. As in eastern North America, preservation is poor in Mesoamerica outside of caves and deserts. Few textiles from prior to the sixteenth century exist.28 Of the known textiles from Mesoamerica, few retain traces of blue pigment, though Irmgard Johnson did study a group of Maya textiles with blue decoration.29 She also found that blue, grayish-blue, and blue-green yarns were occasionally used in Chichimeca textiles from Candelaria Cave in Coahuila, Mexico.30 Indigo blue was identified in Chihuahua textiles from the Tehuacan valley of Mexico,31 and a tie-dyed fabric from Don Bonfilio Cave—whose decoration is similar to the motif found in the Casa Grande tie-dyed cloth noted above—has a blue ground that was identified as indigo.32

Maya Blue

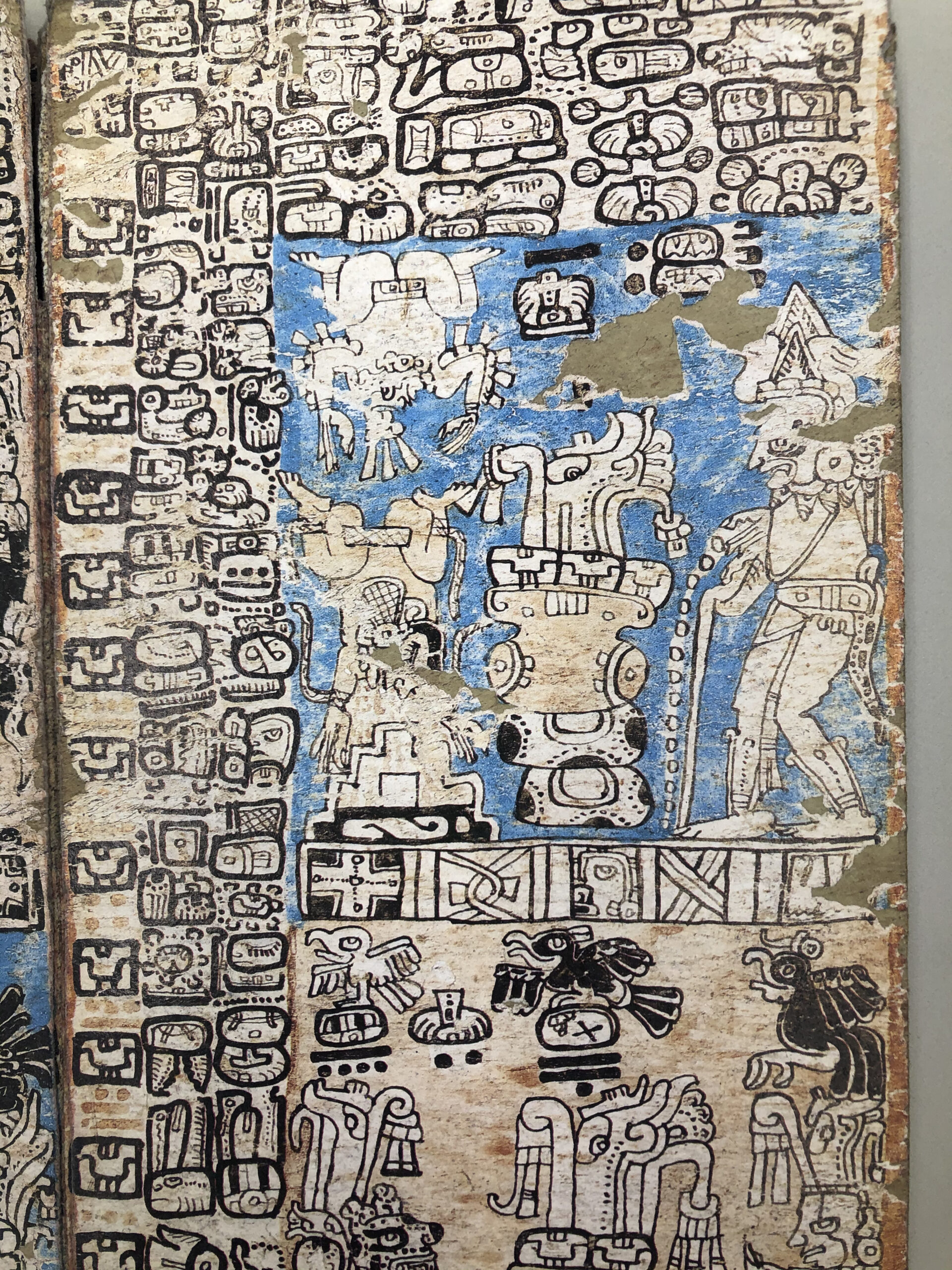

Maya blue is a remarkable and enduring pigment used by the ancient Maya. This vibrant blue-to-blue-green color was used in various forms of art, including murals, pottery, and codices (Figure 3).33 Maya blue pigment is made by thermally treating a mixture of indigo and palygorskite clay.34 It is known for its remarkable resistance to fading and deterioration. This property is attributed to the chemical bond formed between the indigo molecules and the palygorskite, which stabilizes the pigment and allows it to be applied like a paint. This has allowed Maya blue to survive archaeologically, whereas vegetal fibers dyed with indigo largely have not.

Maya blue is not only a testament to the technical expertise of the ancient Maya but also an intriguing example of their understanding of chemistry and materials science. Its ingredients are as follows:

1. Indigo, derived from the leaves of the indigo plant (most likely I. suffruticosa), was used as the source of indigotin, the dark-blue crystalline compound that is the main constituent of indigo dye.

2. A type of clay known as palygorskite, also called attapulgite, is abundant in certain regions of Mesoamerica and served as a binding material.

3. Sustained low heat (<302°F [150°C]) provided the energy needed to create chemical and physical stability.35 The source of heat may have been copal incense.36

Interestingly, all three ingredients (indigo, palygorskite, and copal) have healing qualities, which suggests that the preparation of Maya blue may have had ritual significance.37

The exact techniques and variations of Maya blue production remain obscure and may have differed by region over time. For instance, we do not know whether the dry or wet form of indigo was used. Dry indigo in the form of loaves or cakes could have been stored or transported. Fresh leaves had to be processed immediately and could only be harvested from October to February.38 Sonia Ovarlez notes that the two processes produce forms that are distinguishable under magnification; however, this work on archaeological materials remains to be done. As noted above, if Mesoamerican people were producing dry indigo, it could have been used by people of the U.S. Southwest if they were not growing indigo locally or importing dyed yarns.

South America

Indigo use among Indigenous South Americans was both ancient and widespread. According to textile-dyeing researcher Dominique Cardon, “The evidence of vast numbers of archaeological textiles discovered in Peru … show that, since pre-Columbian times, the Indian people of … South America had been skilled in the use of indigo … as a textile dye.”39

Indigo was likely an integral part of cultural and artistic traditions in South America, and the Indigenous people there had a deep understanding of indigo-dyeing techniques. But unlike most other regions, the western coast of South America, from central Peru to northern Chile, is one of the driest places on earth, providing the perfect conditions for preservation. Most of the evidence for the use of indigo as a dye comes from this region. Indigofera suffruticosa Miller and several other indigo-producing plants were available in South America, including I. truxillensis, Koanophyllon tinctorium Arruda, and Cybistax antisyphilitica Martius (yangua).40

Specific practices involving indigo likely varied across the regions and cultures of South America, and indigo may have been more prevalent in certain areas. For instance, indigo pigment was applied to pottery more than 2,000 years ago in the Paracas region on the southern coast of Peru.41 However, this technique does not seem to have been practiced in other regions. It is possible that indigo slip, or “paint,” if it was used elsewhere in South America, simply did not preserve well.

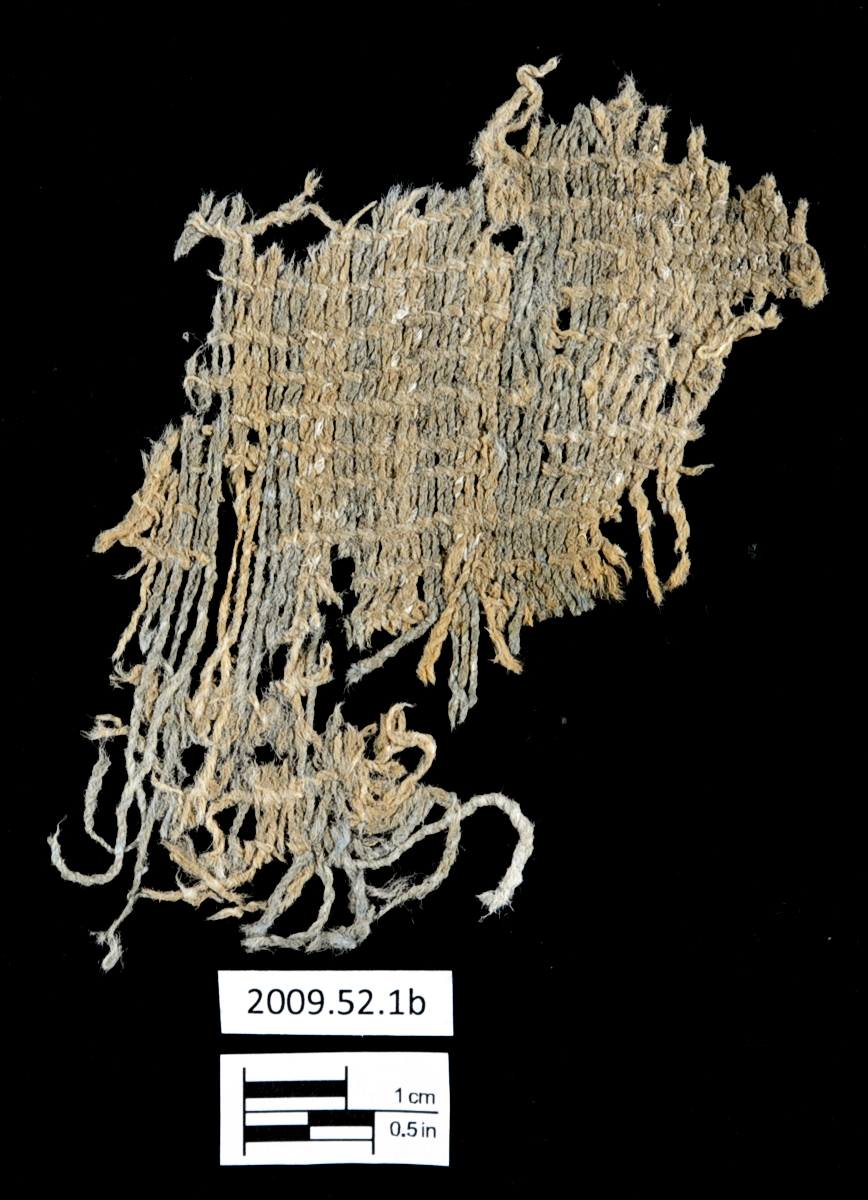

While there are accounts from Spanish chroniclers who witnessed Inka indigo practices,42 what we know about the early use of indigo comes largely from archaeological textiles. There are many, many examples, and virtually all tested samples contain indigo.43 It is clear that indigo production was highly developed in South America from very early times, and both cotton and camelid hair (llama and alpaca) were dyed with indigo.

As mentioned above, the earliest documented use of indigo in South America (and the world) is from the preceramic site of Huaca Prieta, where cotton fabrics were dyed with indigo 6,200 years ago (Figure 4).44 Most early examples of blue come from the Paracas region, where indigo has been identified in Paracas Necropolis textiles likely dating to 250 BCE–150 CE.45 Even earlier but untested examples from the Paracas Peninsula include cotton textiles with blue dye from the site of Karwa, likely made around 900–500 BCE (Figure 5). Countless other textiles with blue, blue-green, and green yarns have been excavated from the western coast of South America. While nonindigoid sources of blue dye exist in South America—including Justicia colorifera (cuaja tinta or tinta montes) and some dark purple species of potato (e.g., Solanum stentomum)—they are not included in the present discussion.46

Indigo was processed at Huaca Prieta before pottery was introduced. So, what did the dyers use as containers? No stone or wooden bowls large enough to serve as vats have been excavated; however, there are many fragments of gourds that would have been suitable. Based on this information, several sets of experiments were conducted using gourds as containers. We attempted to produce indigo blue using materials that would have been readily available to the people of Huaca Prieta. All experiments were done using fresh leaves from plants grown in the area of Washington, D.C. Our procedures and findings, discussed below in reports by Kathleen Martin and Catharine Ellis, suggest that yarns could have been dyed with indigo in small batches using fresh leaves, gourds, water, and either wood ash or burnt shell.

I. Experiments using fresh leaves with urine in gourds

Kathleen Martin

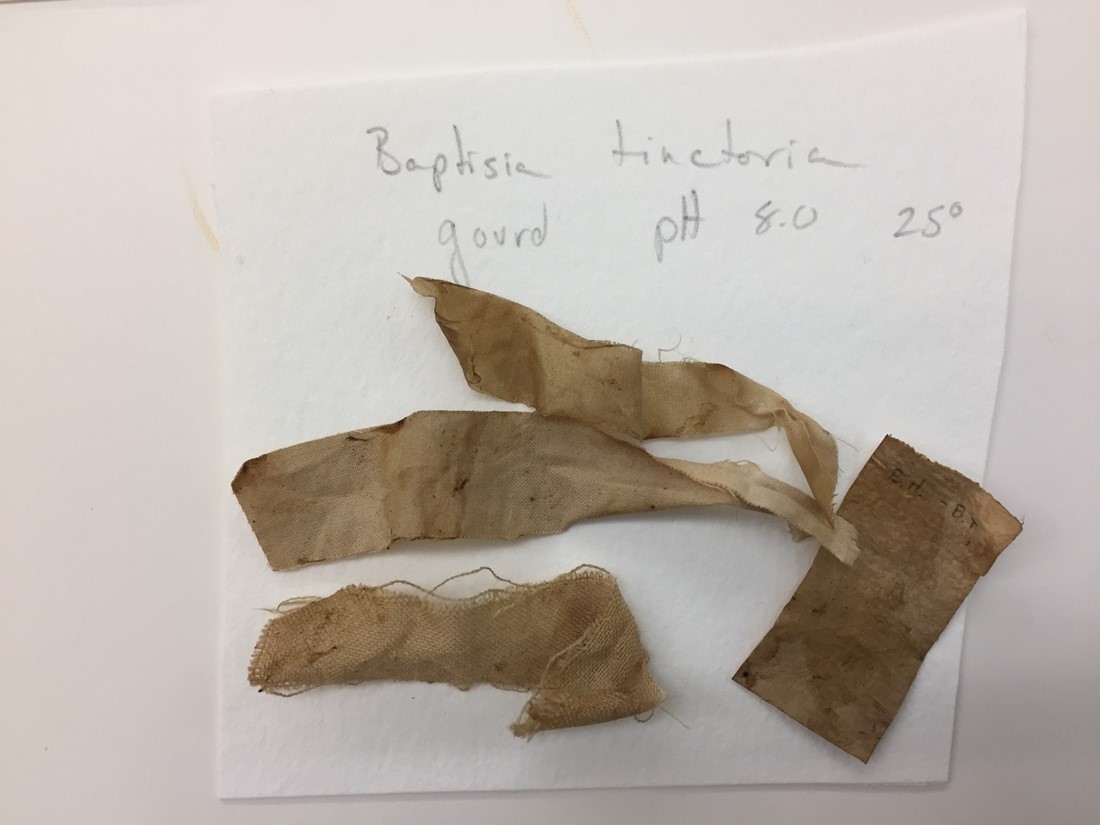

The first experiments were carried out in 2018 by Leah Bright, Elizabeth Knight, Susan Heald, Emily Kaplan, and Jeffrey C. Splitstoser at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) Cultural Resources Center in Suitland, Maryland, using Indigofera suffruticosa, Indigofera tinctoria (añil), Baptisia tinctoria (yellow wild indigo), Isatis tinctoria (woad), and Persicaria tinctoria (Japanese indigo), each in a separate vat.

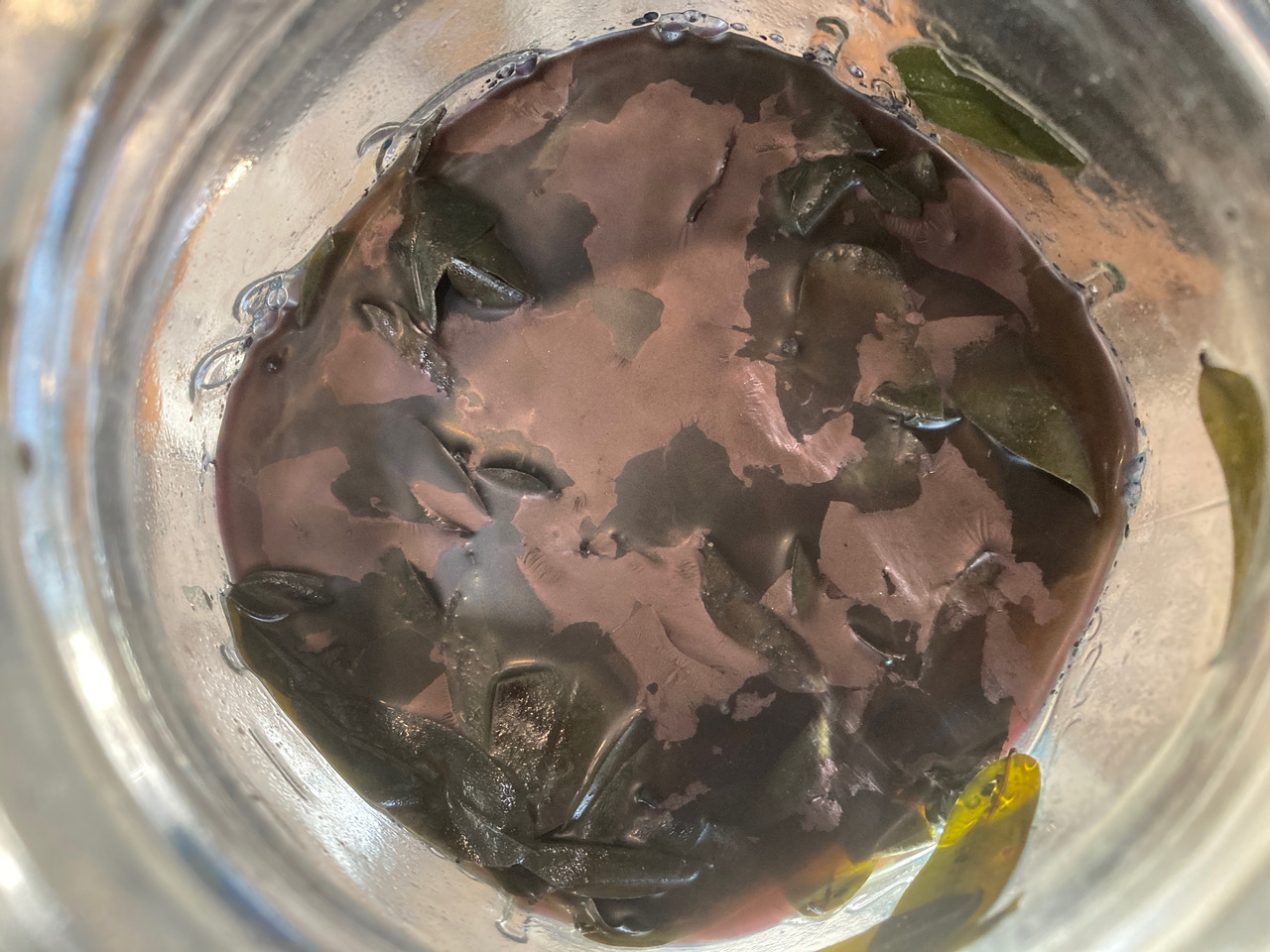

These experiments investigated the possibility of dyeing cotton fabric with indigo leaves in gourds using urine as a source of alkalinity. Since Huaca Prieta was a preceramic culture, the choice of vessel for dyeing is unknown. These experiments used leaves from each of the five indigo plants to create vats in gourds (Figure 6) and then repeated the experiments in glass beakers.

The leaves were heated by sunlight outdoors and stored in a sealed fume hood overnight to maintain temperature (Figure 7).

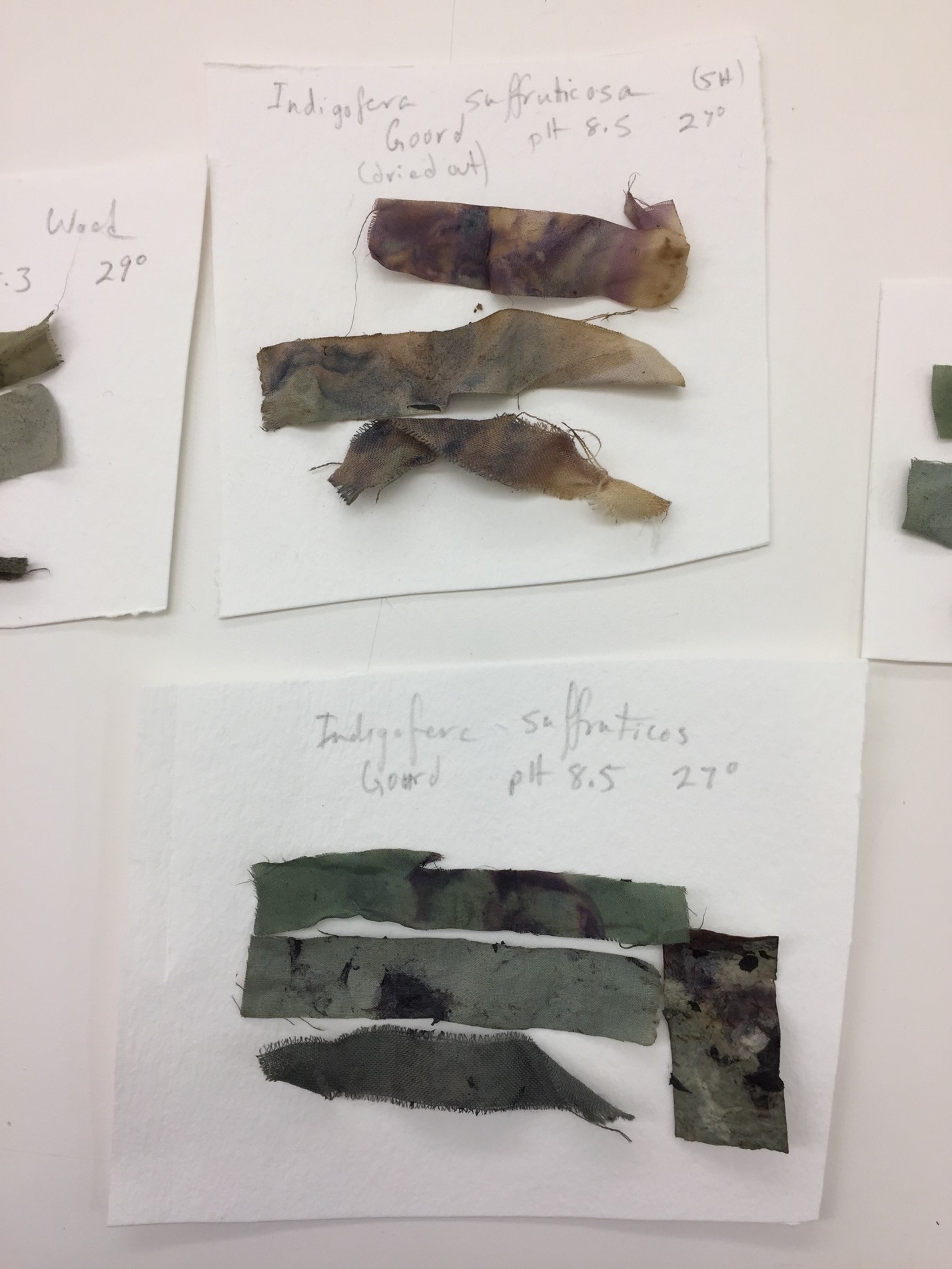

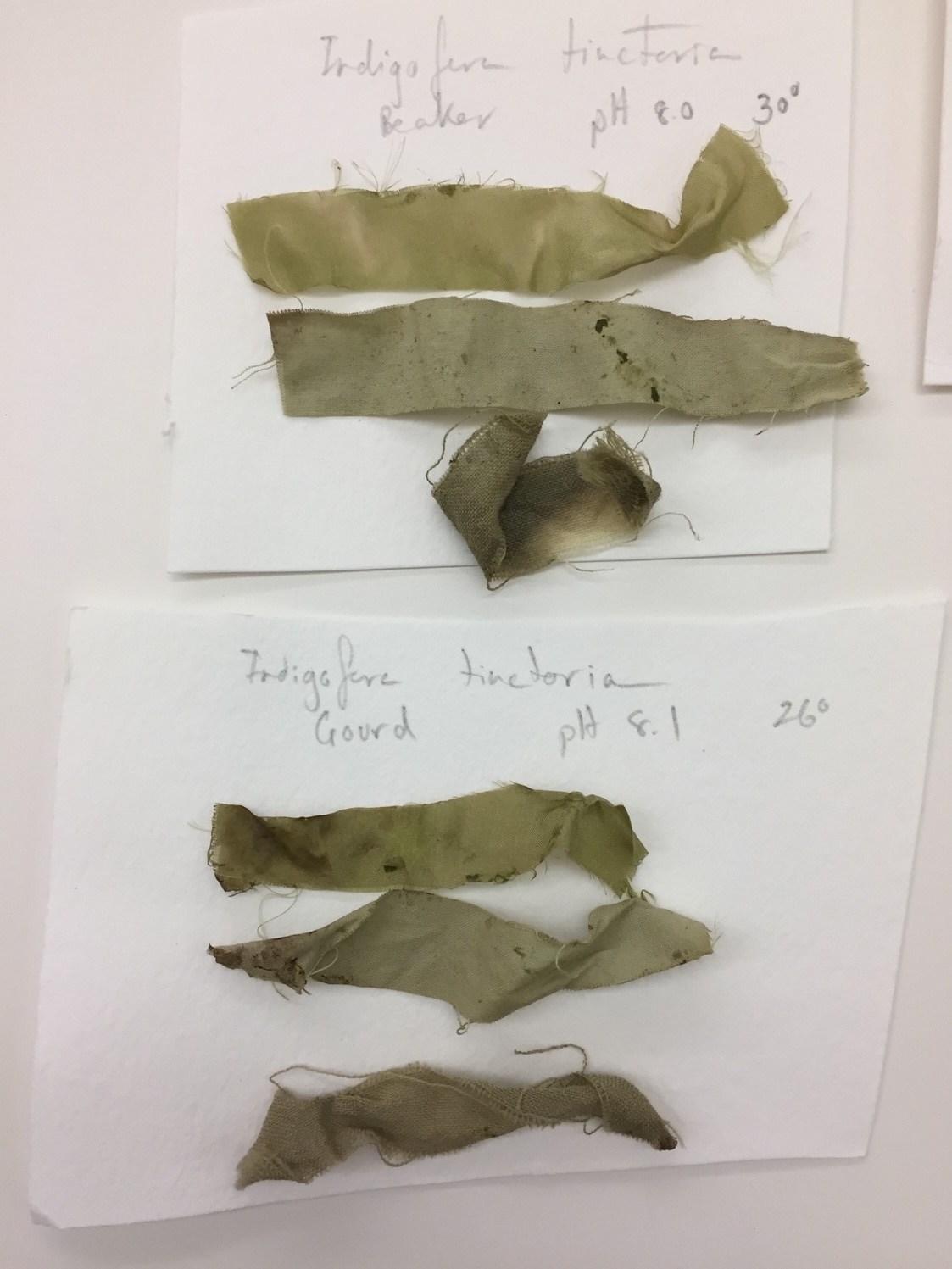

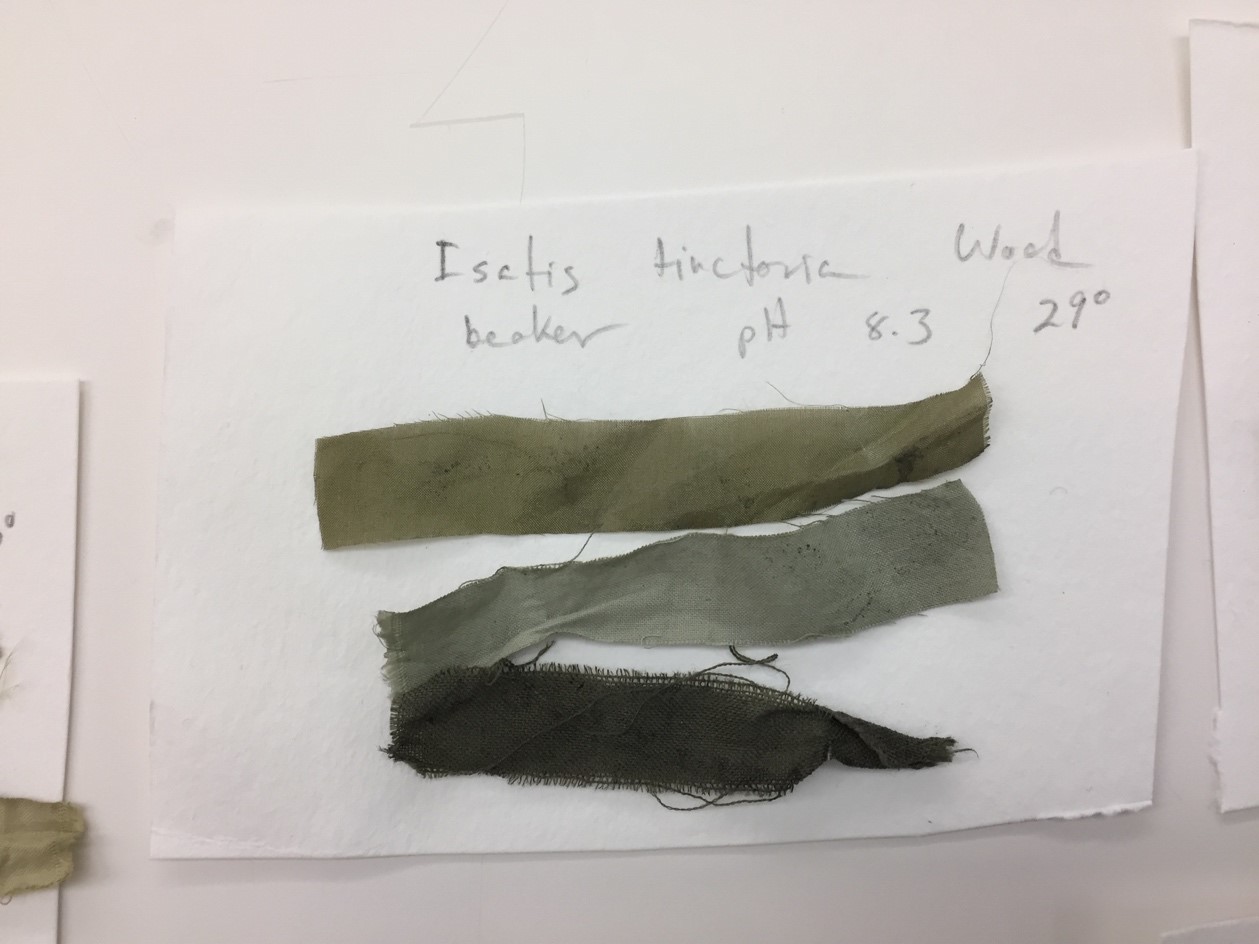

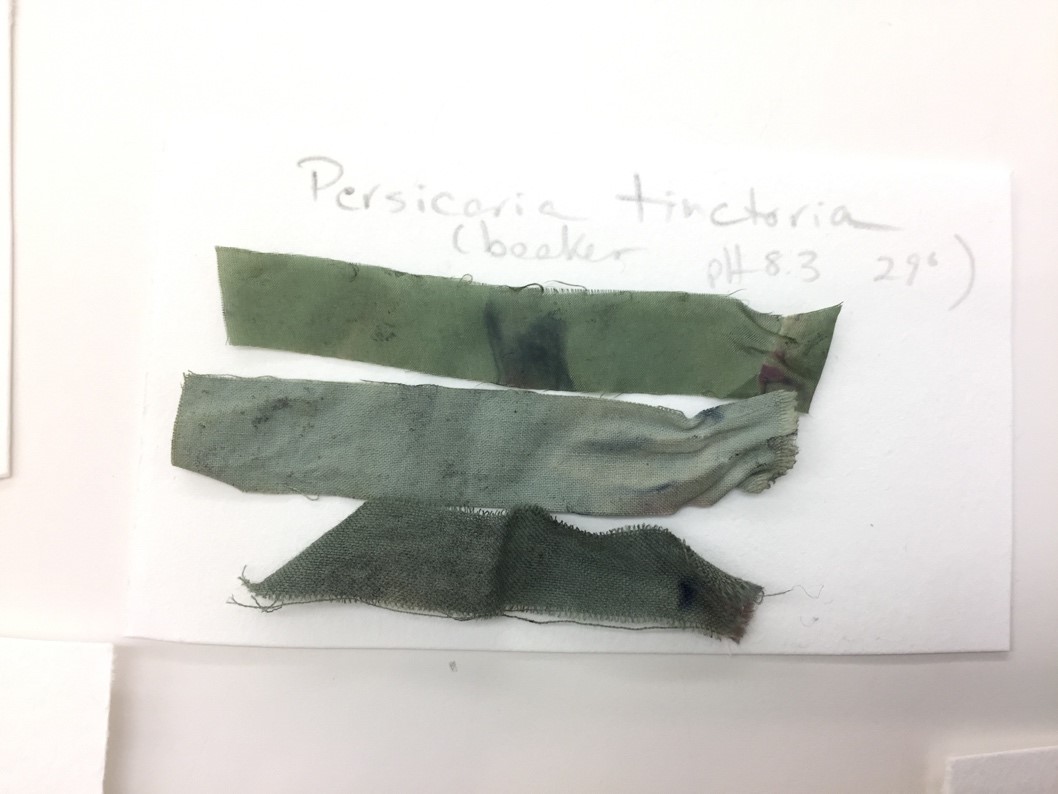

The vats were mostly successful at producing color; I. suffruticosa’s leaves produced richer green-blue coloring (Figure 8), I. tinctoria produced greens (Figure 9), and Isatis tinctoria and P. tinctoria produced bluish greens (Figures 10–11).

The B. tinctoria vats, however, produced a yellowish-brown color, with no evidence of blue or green (Figure 12).

II. Experiments using wood ash and Asimina triloba (pawpaw) fruit

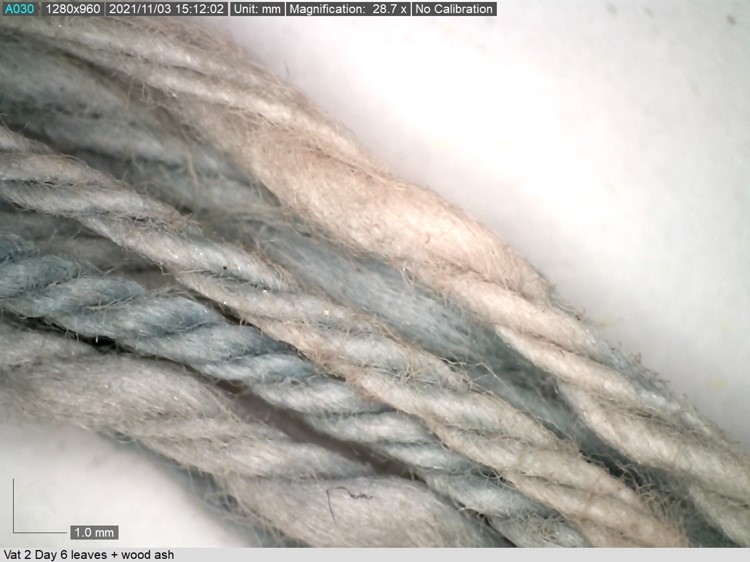

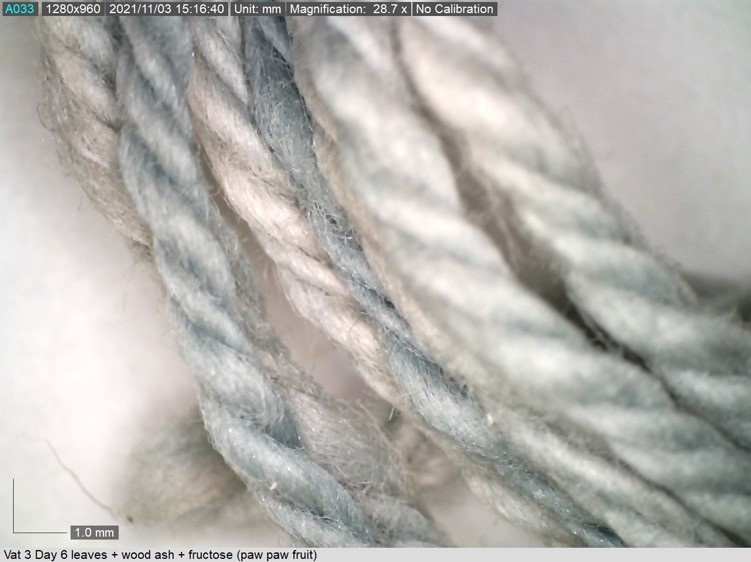

Another set of experiments was carried out by Heald, Splitstoser, and Martin in 2021 at NMAI using wood ash with I. suffruticosa in glass beakers. These experiments used wood ash with macerated pawpaw fruit. Like the previous experiments at NMAI, the leaves were retained in the dye vat and not removed during the dyeing process. A second objective was to see if exposure to oxygen by massaging and repeated oxidation or the addition of a sugar, fructose, increased the production of blue coloration on cotton.

Four vats were produced using only freshly picked I. suffruticosa leaves. The leaves were covered with water, and a mesh screen kept them submerged. The vats were kept warm on a heated mat, and after twenty-four hours, wood ash was stirred into the water and cotton yarn bundles were added. For the odd-numbered vats, leaves were left in the vats and lightly stirred. For the even-numbered vats, the yarn was massaged and removed, then returned to the vats, increasing exposure to oxygen. In vats 3 and 4, macerated pawpaw fruit was used as a source of fructose.47

The dye results showed greater blue colors when the yarn was massaged, aired, and dipped again. In the vats with fructose, the yarn developed blue coloring on the second day of dyeing (Figures 13–17). All yarns showed evidence of blue, whereas the pink coloration was likely from indirubin, a compound naturally present in indigo-producing plants.

Future experiments would use burnt shell instead of wood ash to modify the pH (as described by Catharine Ellis below).

An additional set of experiments was completed in 2020 during the COVID-19 epidemic by Karthika Audinet, Catharine Ellis, and Splitstoser using I. suffruticosa leaves with soda ash as the source of alkalinity.

I. Experiments using fresh I. suffruticosa leaves and wood ash

Catharine Ellis

The first step in preparing fresh leaves for dyeing was to soak them overnight, extracting a bronze-colored liquid. This liquid contains indican, a precursor to indoxyl, the dye that ultimately imparts the blue color to the textiles. But, once extracted from the leaves, the dye is not soluble in water and cannot be used as a dye. The indigo dye is made soluble only under certain circumstances: an alkaline environment plus fermentation, or the use of a sugar reduction. This transforms the indigo molecule, making it soluble, and is referred to as an “indigo dye vat.”

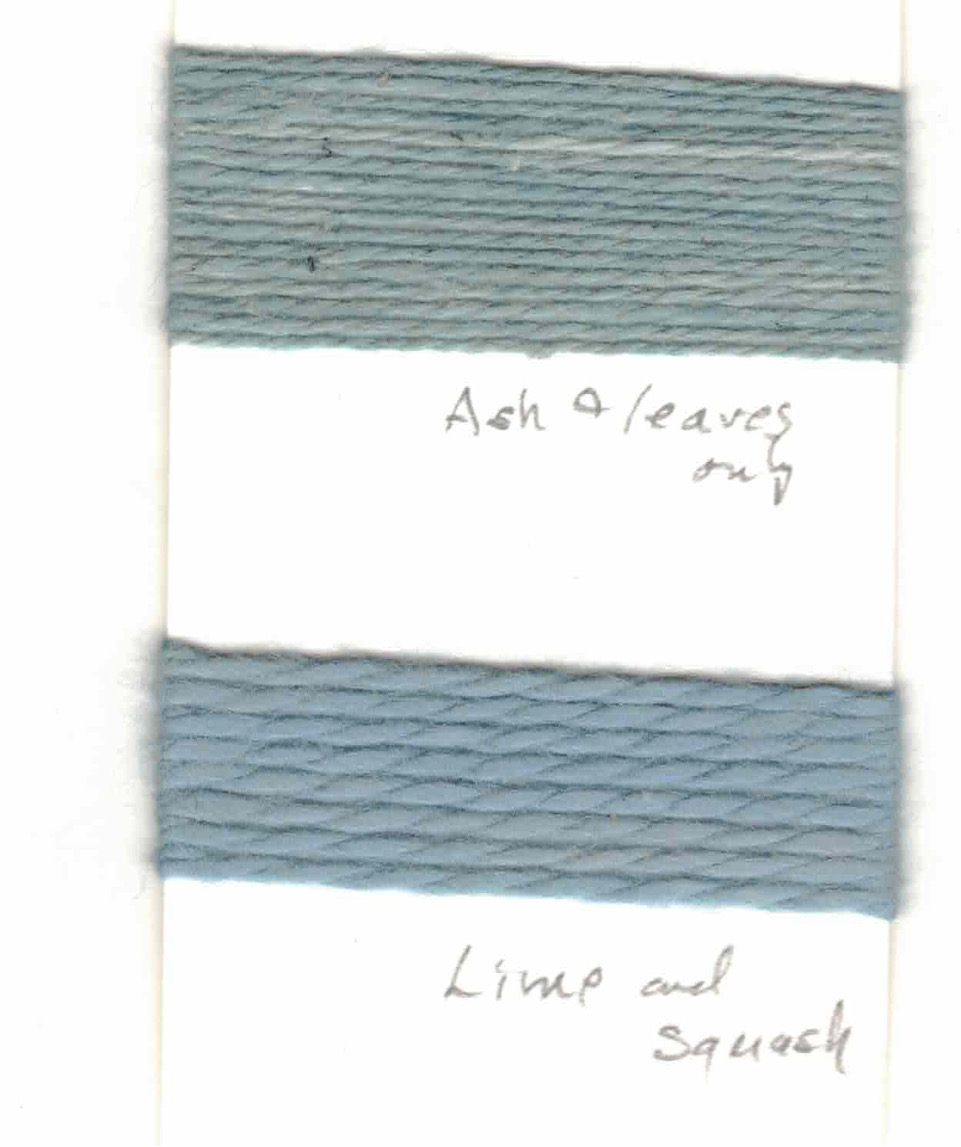

In our first experiments, we added wood ash directly to the liquid leaf extraction as a source of alkalinity. The leaves were left in the vessel (a glass jar or dried gourd) in the hope that the leaves would contain some sugars that would help to reduce the indigo. Evidence of success was an iridescent surface on the liquid and a yellowish color beneath (Figure 18). Cotton yarn, when left to soak in this leaf/ash mixture, came out a greenish color, which oxidized to a pale grayish blue.

II. Experiments using fresh I. suffruticosa leaves and lime

Two years later, we repeated the process with some changes learned from the 2021 experiments (see below). The fresh leaves were soaked as before, and then removed from the bronze-colored liquid. Lime (calcium hydroxide), which would have been available in the form of burnt shell, was used as a more refined and concentrated source of alkalinity. A fresh gourd was used as the vessel, in the hope that the flesh of the gourd would be a source of sugar and result in a better reduction of the indigo. The resulting dyed color from these experiments was a much clearer blue (Figure 19).

The simplicity of this process and of using materials readily at hand led me to believe that this was a possible approach to dyeing with indigo during this period. It is easy to imagine that these little “dye vats” were used once and then discarded. Today we are more apt to make and maintain similar vats for long-term use.

Medicinal Uses of Indigo

Interestingly, in addition to their use as a source of blue, indigo-producing plants were employed by many Indigenous communities for their medicinal qualities. For example, Paul Hamel and Mary Chiltoskey note the use of B. australis/B. tinctoria by the Cherokee as an anti-inflammatory, a gynecological aid, a source of gastrointestinal relief, and a toothache remedy.48

The specific species of Baptisia used and the methods of preparation and application would have varied among groups. Daniel Moerman notes that the Delaware, Iroquois, Micmac, Mohegan, Nanticoke, Ojibwa, and Penobscot used B. tinctoria as a medicine for dermatological, gynecological, antirheumatic, gastrointestinal, liver, orthopedic, antihemorrhagic, and venereal aids.49

In Mesoamerica, a treatment for mange included “the dregs or lees of oil of indigo.”50 A remedy for oral infections involved the “tips of the indigo plant slightly ground … the juice is to be well pressed out and poured on the throat immediately.”51

Conclusions

The present essay has primarily discussed the use of indigo in textiles; however, indigo was also used to decorate basketry, ceramics, and murals. Several examples of basketry from Huaca Prieta have blue-gray elements, which suggests they were colored with indigo.52 Some of the baskets from the Paracas site of Cerrillos in the Ica Valley of Peru are decorated with blue elements that are likely indigo (Figure 20). While evidence for the use of indigo in northeastern basketry is not known before the early nineteenth century,53 it would not be surprising if earlier examples are eventually found.

In summary, it is clear that indigo was well-established and culturally significant for thousands of years in the Americas. Native Americans used these native plants to create both indigo blue and medicine, demonstrating not only resourcefulness but also a deep knowledge of the natural world. Indigo cultivation and dyeing techniques were likely passed down through generations and played a vital role in the cultural and economic life of many Native American societies. The arrival of Spanish conquistadors and colonists changed the Indigenous use of indigo, as European methods and preferences for dyeing prevailed. Nevertheless, the legacy of Indigenous indigo traditions continues to influence Indigenous and Western art and culture.

Acknowledgments

First, we wish to thank Barbara Hanson Forsyth for conceiving of, and inviting us to participate in, this wonderful exhibition, Blue Gold, and we thank Emily Hanna of Mingei International Museum for her amazing help and support. We are also grateful to Penelope Drooker, who helped with much of the archaeological evidence for indigo use in the northeastern United States; Laurie Webster, for her immense help with the discussion of use of indigo in the U.S. Southwest; and Lisa DeLeonardis, for her insights regarding the use of indigo on painted Paracas ceramics. We want to specially thank Emily Kaplan and Susan Heald, who initiated and sponsored the series of indigo experiments conducted at NMAI, as well as Karthika Audinet, who coordinated the experiments that were done during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, we appreciated the work of Jean Patterson, whose editorial skills greatly improved the essay.

Notes

-

Jeffrey C. Splitstoser et al., “Early Pre-Hispanic Use of Indigo Blue in Peru,” Science Advances 2, no. 9 (2016): 1–4, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501623; Tom D. Dillehay et al., “Chronology, Mound-Building, and Environment at Huaca Prieta, Coastal Peru, from 13,700 to 4,000 Years Ago,” Antiquity 86 (2012): 48–70; Thomas D. Dillehay, ed., Where the Land Meets the Sea: Fourteen Millennia of Human History at Huaca Prieta, Peru (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017). ↩︎

-

Both genera belong to the Fabaceae, or pea, family. ↩︎

-

Penelope Ballard Drooker, Mississippian Village Textiles at Wickliffe (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1992), 234–35; Drooker, “The Fabric of Power: Textiles in Mississippian Politics and Ritual,” in Forging Southeastern Identities: Social Archaeology, Ethnohistory, and Folklore of the Mississippian to Early Historic South, ed. Gregory A. Waselkov and Marvin T. Smith (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2017), 22, 28; see also Lucy R. Sibley and Kathryn A. Jakes, “Coloration in Etowah Textiles from Burial No. 57,” in Archaeometry of Pre-Columbian Sites and Artifacts, ed. David A. Scott and Pieter Meyers (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 1994), 395. ↩︎

-

Mary Elizabeth King and Joan S. Gardner, “The Analysis of Textiles from Spiro Mound,” in The Research Potential of Anthropological Museum Collections, ed. King and Gardner (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, New York, 1981), 123–39; Jenna Tedrick Kuttruff, “Textile Attributes and Production Complexity as Indicators of Caddoan Status Differentiation in the Arkansas Valley and Southern Ozark Regions” (PhD diss., Ohio State University, Columbus, 1988), 117–18; Sibley and Jakes, “Coloration”; Charles C. Willoughby, “Textile Fabrics from the Spiro Mound.” ↩︎

-

Christel M. Baldia, “Development of a Protocol to Detect and Classify Colorants in Archaeological Textiles and Its Application to Selected Prehistoric Textiles from Seip Mound in Ohio” (PhD diss., Ohio State University, Columbus, 2005); Christel M. Baldia et al., “Coloration and Fabric Structure of Selected Polychrome Textiles from the Seip Mound Group,” Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 33, no. 2 (2008): 197–222. Baldia also encountered white, gray, red, yellow, and black pigments. ↩︎

-

Baldia et al., “Coloration and Fabric Structure,” 214; Baldia, “Development of a Protocol,” 7, 97–98. ↩︎

-

Penelope Ballard Drooker, personal communication with the author, December 2022; Linda Welters and Margaret T. Ordonez, “Blue Roots and Fuzzy Dirt: Archaeological Textiles from Native American Burials,” in Perishable Material Culture in the Northeast, ed. Penelope Ballard Drooker (Albany: University of the State of New York, 2004), 191. ↩︎

-

Baldia, “Development of a Protocol,” 32. See also William T. Stern, “Ventenat’s ‘Decas Generum Nororum’ (1808),” in Essays in Biohistory and Other Contributions Presented by Friends and Colleagues to Frans Verdoorn on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday, ed. P. Smit and Rodolphine J. Ch. V. ter Laage (Utrecht: International Association of Plant Taxonomy, 1970), 343–52. ↩︎

-

For example, Rita Buchanan, A Weaver’s Garden (Loveland, Colo.: Interweave Press, 1987), 115; Harriette S. Kellogg, “Native Dye-Plants and Tan-Plants of Iowa, with Notes on a Few Other Species,” Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 19, no. 1 (1912): 9, https://scholarworks.uni.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6755&context=pias. ↩︎

-

John Cannon and Margaret Cannon, Dye Plants and Dyeing (Portland, Ore.: Timber Press in association with The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2004), 26; see also David H. Rembert Jr., “The Indigo of Commerce in Colonial North America,” Economic Botany 33, no. 2 (1979): 128–34. ↩︎

-

For example, see Anna Gambold, “Plants of the Cherokee Country: A List of Plants Found in the Neighborhood of Connasarga River (Cherokee Country), Where Springfield Is Situated,” American Journal of Science 1 (1818): 251; Esaias Hollberg, Norra Americanska Färge Örter (thesis, University of Åbo, Åbo, Finland, 1763), 31–32; see also William H. Banks Jr., “Ethnobotany of the Cherokee Indians” (master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, 1953), 68, https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1052; Paul B. Hamel and Mary U. Chiltoskey, Cherokee Plants: Their Uses—a 400 Year History (n.p.: Paul B. Hamel and Mary U. Chiltoskey, 1975), 40. ↩︎

-

Lynn S. Teague, Textiles in Southwestern Prehistory (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998), 131–35. ↩︎

-

Kate Peck Kent, Prehistoric Textiles of the Southwest, School of American Research Southwest Indian Arts Series (Santa Fe and Albuquerque: School of American Research and University of New Mexico Press, 1983), 43. ↩︎

-

Walter Hough, Culture of the Ancient Pueblos of the Upper Gila River Region, New Mexico and Arizona: Second Museum-Gates Expedition, Bulletin of the United States National Museum 87 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1914), 83; but see Mary Elizabeth King, “Medio Period Perishable Artifacts: Textiles and Basketry,” in Casas Grandes: A Fallen Trading Center of the Gran Chichimeca, ed. Charles C. Di Peso, John B. Rinaldo, and Gloria J. Fenner, Amerind Foundation Publication 9 (Dragoon, Ariz.: Amerind Foundation, 1974). ↩︎

-

Michael Kasha, “Appendix: Chemical Notes on the Coloring Matter of Chihuahua Textiles of Pre-Columbian Mexico,” in Textiles of Pre-Columbian Chihuahua, ed. Lila Morris O’Neale, Contributions to American Anthropology and History 45 (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1948), 151–57. ↩︎

-

Laurie D. Webster, Kelley A. Hays-Gilpin, and Polly Schaafsma, “A New Look at Tie-Dye and the Dot-in-a-Square Motif in the Prehispanic Southwest,” Kiva 71, no. 3 (2006): 317–48. ↩︎

-

Laurie D. Webster, personal communication with the author, November 2022. ↩︎

-

Ibid.; see also Mary-Russell Colton, Hopi Dyes (Flagstaff, Ariz.: Northern Arizona Society of Sciences and Art, 1965), 50–51. ↩︎

-

Laurie Diane Webster, “Effects of European Contact on Textile Production and Exchange in the North American Southwest: A Pueblo Case Study” (PhD diss., University of Arizona, Tucson, 1997), https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/282534; Laurie D. Webster, “The Economics of Pueblo Textile Production and Exchange in Colonial New Mexico,” in Beyond Cloth and Cordage: Archaeological Textile Research in the Americas, ed. Penelope Ballard Drooker and Laurie D. Webster (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2000), 179–204. See the section on Maya blue below. ↩︎

-

Hermann M. Niemeyer and Carolina Agüero, “Dyes Used in Pre-Hispanic Textiles from the Middle and Late Intermediate Periods of San Pedro de Atacama (Northern Chile): New Insights into Patterns of Exchange and Mobility,” Journal of Archaeological Science 57 (2015): 14–23. Camelids include llama, guanaco, alpaca, and vicuña. ↩︎

-

Webster, personal communication with the author, November 2022. ↩︎

-

Dominique Cardon, Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science (London: Archetype, 2007), 337; Ana Roquero and Witold Nowik, “Tintes azules de Mesoamérica: Muicle; un sucedáneo del azul añil,” in Actas III Jornadas Internacionales sobre Textiles Precolombinos, ed. Victòria Solanilla Demestre (Barcelona: Grup d’Estudis Precolombins, Departament d’Art de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2006), 21. ↩︎

-

Cardon, Natural Dyes, 405; R. M. King and H. Robinson, The Genera of the Eupatorieae (Asteraceae), Monographs in Systematic Botany 22 (St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden, 1987), 317. K. albicaule produces a green color. ↩︎

-

Patricia Rieff Anawalt, “The Emperors’ Cloak: Aztec Pomp, Toltec Circumstances,” American Antiquity 55, no. 2 (1990): 291–307; Anawalt, “Riddle of the Emperor’s Cloak: The Design Motif on the Robes of Aztec Rulers May Well Represent a Claim of Political Legitimacy with Roots Deep in the Toltec Past,” Archaeology 46, no. 3 (1993): 30–36. ↩︎

-

This term is alternately spelled xiuhquihuitl. ↩︎

-

Bernardino de Sahagún, Digital Florentine Codex: An Encyclopedia of 16th-Century Indigenous Mexico, trans. García Garagarza (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2023), bk. 8, fol. 31r, https://florentinecodex.getty.edu. Sahagún produced the Florentine Codex with Antonio Valeriano, Alonso Vegerano, Martín Jacovita, Pedro de San Buenaventura, and twenty-two anonymous Nahua artists. ↩︎

-

Ibid., bk. 11, fol. 219r. ↩︎

-

But see Irmgard Weitlaner Johnson, “Chiptic Cave Textiles from Chiapas, Mexico,” Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris 43 (1954): 137–47; Johnson, “Textiles,” in Nonceramic Artifacts, ed. Richard S. MacNeish, Antoinette Nelken-Terner, and Irmgard Weitlaner Johnson, The Prehistory of the Tehuacan Valley 2, gen. ed. Douglas S. Byers (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1967), 189–226; Johnson, Los textiles de la cueva de la Candelaria, Coahuila, Coleccion Cientifica Arqueología 51 (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1977); Mary Elizabeth King, “The Prehistoric Textile Industry of Mesoamerica,” in The Junius B. Bird Pre-Columbian Textile Conference, May 19th and 20th, 1973, ed. Ann Pollard Rowe, Elizabeth P. Benson, and Anne-Louise Schaffer (Washington, D.C.: Textile Museum & Dumbarton Oaks, 1979), 265–78. ↩︎

-

Johnson, “Chiptic Cave Textiles.” ↩︎

-

Johnson, Los textiles de la cueva de la Candelaria, 50, 52, 150. ↩︎

-

Johnson, “Textiles,” 194–96; Kasha, “Appendix.” ↩︎

-

Alba Guadalupe Mastache de Escobar, “Dos Fragmentos de Tejido Decorados con la Tecnica de Plangi,” Anales del Instituto Nacional de Antropolgia e Historia 7a, no. 4 (1974): 251–62. ↩︎

-

Élodie Dupey García, “The Materiality of Color in Pre-Columbian Codices: Insights from Cultural History,” Ancient Mesoamerica 28 (2017): 21–40. ↩︎

-

M. Sánchez del Río et al., “Crystal-Chemical and Diffraction Analyses of Maya Blue Suggesting a Different Provenance of the Palygorskite Found in Aztec Pigments,” Archaeometry 63, no. 4 (2021): 738. ↩︎

-

L. M. Torres, “Maya Blue: How the Mayas Could Have Made the Pigment,” Materials Issues in Art and Archaeology: Proceedings of the Materials Research Society (Pittsburgh: Materials Research Society, 1988), 123–28; H. van Olphen, “Maya Blue: A Clay-Organic Pigment?” Science, n.s. 154, no. 3749 (1966): 645–46. ↩︎

-

Dean E. Arnold et al., “The First Direct Evidence for the Production of Maya Blue: Rediscovery of a Technology,” Antiquity 82, no. 315 (2008): 151–64. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 153. ↩︎

-

Sonia Ovarlez, “Comentarios respecto al estudio del azul maya,” La pintura mural prehispánica en México, ed. Leticia Staines Cicero (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2004), 69. ↩︎

-

Cardon, Natural Dyes, 348. ↩︎

-

See, for example, David G. Beresford-Jones and Oliver Q. Whaley, “Nasca Domestic Culture: The Significance of Past Environments for Reading the Material Culture of the South Coast of Peru,” Ñawpa Pacha 42, no. 2 (2022): 163–83; Cardon, Natural Dyes, 404–8; see also Splitstoser et al., “Early Prehispanic Use of Indigo Blue in Peru,” 2. ↩︎

-

Dawn Kriss et al., “A Material and Technical Study of Paracas Painted Ceramics,” Antiquity 92, no. 366 (2018): 1492–1510. ↩︎

-

Bernabé Cobo, Historia del Nuevo Mundo, Biblioteca de Autores Españoles 91–92 (Madrid: Ediciones Atlas, 1956). ↩︎

-

For example, Jennifer Campos Ayala et al., “Characterizing the Dyes of Pre-Columbian Andean Textiles: Comparison of Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry and HPLC-DAD,” Heritage 4, no. 3 (2021): 1639–59; Mary Elizabeth King, “Analytical Methods and Prehistoric Textiles,” American Antiquity 43, no. 1 (1978): 89–96; Rudolph H. Michel, Patrick E. McGovern, and Joseph Lazar, “Indigoid Dyes in Peruvian and Coptic Textiles of the University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology,” Archeomaterials 6, no. 1 (1992): 69–83; Niemeyer and Agüero, “Dyes used in Pre-Hispanic Textiles”; Francesca Sabatini et al., “Revealing the Organic Dye and Mordant Composition of Paracas Textiles by a Combined Analytical Approach,” Heritage Science 8, no. 122 (2020): 1–17; Arie Wallert and Ran Boytner, “Dyes from the Tumilaca and Chiribaya Cultures, South Coast of Peru,” Journal of Archaeological Science 23 (1996): 853–61; Jan Wouters and Noemí Rosario-Chirinos, “Dye Analysis of Pre-Columbian Peruvian Textiles with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Diode-Array Detection,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 31, no. 2 (1992): 237–55; William J. Young, “Appendix 9: Analysis of Textile Dyes,” in A Chancay-Style Grave at Zapallan, Peru: An Analysis of Its Textiles, Pottery, and Other Furnishings, ed. S. K. Lothrop and Joy Mahler, Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology 50, no. 1 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, 1957), 33–34. ↩︎

-

Splitstoser et al., “Early Prehispanic Use of Indigo Blue in Peru.” ↩︎

-

For example, Kathryn A. Jakes, “Physical and Chemical Analysis of Paracas Fibers,” in Paracas Art and Architecture: Object and Context in South Coastal Peru, ed. Anne Paul (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991), 222–39; Kathryn A. Jakes, J. E. Katon, and Pamela A. Martoglio, “Identification of Dyes and Characterization of Fibers by Infrared and Visible Microspectroscopy: Application to Paracas Textiles,” in Archaeometry ‘90: International Symposium on Archaeometry, 2–6 April 1990, Heidelberg, Germany, ed. Ernst Pernicka and Günther A. Wagner (Basel: Birkhäuser, 1991), 305–15; Gustavo A. Fester, “Some Dyes of an Ancient South American Civilization,” Dyestuffs 40, no. 9 (1954): 238–44. ↩︎

-

For example, Kay K. Antúnez de Mayolo, “Peruvian Natural Dye Plants,” Economic Botany 43, no. 2 (1989): 181–91; Cardon, Natural Dyes. ↩︎

-

We wanted to use a fruit native to Peru but eventually settled on the pawpaw, A. triloba, because it is in the same Annonaceae family as cherimoya, Annona cherimola, and both fruits have a sweet, custard-like meat. ↩︎

-

Hamel and Chiltoskey, Cherokee Plants, 40. ↩︎

-

Daniel E. Moerman, Native American Ethnobotany (Portland, Ore.: Timber Press, 2022), 120–21. ↩︎

-

Emily Walcott Emmart, “An Aztec Medical Treatise, the Badianus Manuscript,” Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine 3, no. 6 (1935): 503. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 505. ↩︎

-

Jeff Illingworth and J. M. Adovasio, “Twined and Woven Artifacts: Basketry and Cordage from Huaca Prieta,” in Where the Land Meets the Sea, ed. Dillehay, 525–56. ↩︎

-

Drooker, personal communication, December 2022; see examples in Sarah Peabody Turnbaugh and William A. Turnbaugh, Indian Baskets (West Chester, Penn.: Schiffer Publishing in collaboration with the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1986). ↩︎

Bibliography

- Anawalt 1990

- Anawalt, Patricia Rieff. “The Emperors’ Cloak: Aztec Pomp, Toltec Circumstances.“ American Antiquity 55, no. 2 (1990): 291–307.

- Anawalt 1993

- Anawalt, Patricia Rieff. “Riddle of the Emperor’s Cloak: The Design Motif on the Robes of Aztec Rulers May Well Represent a Claim of Political Legitimacy with Roots Deep in the Toltec Past.“ Archaeology 46, no. 3 (1993): 30-36.

- Antúnez de Mayolo 1989

- Antúnez de Mayolo, Kay K. “Peruvian Natural Dye Plants.“ Economic Botany 43, no. 2 (1989): 181–91.

- Arnold 2008

- Arnold, Dean E., et al. “The First Direct Evidence for the Production of Maya Blue: Rediscovery of a Technology.“ Antiquity 82, no. 315 (2008): 151–64.

- Baldia 2005

- Baldia, Christel M. “Development of a Protocol to Detect and Classify Colorants in Archaeological Textiles and Its Application to Selected Prehistoric Textiles from Seip Mound in Ohio.“ PhD diss., The Ohio State University, Columbus, 2005.

- Baldia 2008

- Baldia, Christel M., et al., “Coloration and Fabric Structure of Selected Polychrome Textiles from the Seip Mound Group.“ Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 33, no. 2 (2008): 197–222.

- Banks 1953

- Banks, William H., Jr. “Ethnobotany of the Cherokee Indians.“ Master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, 1953, https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1052.

- Beresford-Jones and Whaley 2022

- Beresford-Jones, David G., and Oliver Q. Whaley. “Nasca Domestic Culture: The Significance of Past Environments for Reading the Material Culture of the South Coast of Peru.“ Ñawpa Pacha 42, no. 2 (2022): 163–83.

- Buchanan 1987

- Buchanan, Rita. A Weaver’s Garden. Loveland, Colo.: Interweave Press, 1987.

- Campos Ayala 2021

- Campos Ayala, Jennifer, et al. “Characterizing the Dyes of Pre-Columbian Andean Textiles: Comparison of Ambient Ionization Mass Spectrometry and HPLC-DAD.“ Heritage 4, no. 3 (2021): 1639-59.

- Cannon and Cannon 2004

- Cannon, John, and Margaret Cannon. Dye Plants and Dyeing. Portland, Ore.: Timber Press in association with The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2004.

- Cardon 2007

- Cardon, Dominique. Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science. London: Archetype, 2007.

- Cobo 1956

- Cobo, Bernabé. Historia del Nuevo Mundo. Biblioteca de Autores Españoles 91-92. Madrid: Ediciones Atlas, 1956.

- Colton 1965

- Colton, Mary-Russell. Hopi Dyes. Flagstaff, Ariz.: Northern Arizona Society of Sciences and Art, 1965.

- Dillehay 2012

- Dillehay, Tom D., et al. “Chronology, Mound-Building, and Environment at Huaca Prieta, Coastal Peru, from 13,700 to 4,000 Years Ago.“ Antiquity 86 (2012): 48-70.

- Dillehay 2017

- Dillehay, Thomas D., ed. Where the Land Meets the Sea: Fourteen Millennia of Human History at Huaca Prieta, Peru. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017.

- Drooker 1992

- Drooker, Penelope Ballard. Mississippian Village Textiles at Wickliffe. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1992.

- Drooker 2017

- Drooker, Penelope Ballard. “The Fabric of Power: Textiles in Mississippian Politics and Ritual.” In Forging Southeastern Identities: Social Archaeology, Ethnohistory, and Folklore of the Mississippian to Early Historic South, edited by Gregory A. Waselkov and Marvin T. Smith, 16-40. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2017.

- Dupey García 2017

- Dupey García, Élodie. “The Materiality of Color in Pre-Columbian Codices: Insights from Cultural History.“ Ancient Mesoamerica 28 (2017): 21-40.

- Emmart 1935

- Emmart, Emily Walcott. “An Aztec Medical Treatise, the Badianus Manuscript.“ Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine 3, no. 6 (1935): 485-506.

- Fester 1954

- Fester, Gustavo A. “Some Dyes of an Ancient South American Civilization.“ Dyestuffs 40, no. 9 (1954): 238-44.

- Gambold 1818

- Gambold, Anna. “Plants of the Cherokee Country: A List of Plants Found in the Neighborhood of Connasarga River (Cherokee Country), Where Springfield Is Situated.“ American Journal of Science 1 (1818): 241-51.

- Hamel and Chiltoskey 1975

- Hamel, Paul B., and Mary U. Chiltoskey, Cherokee Plants: Their Uses—a 400 Year History. N.p.: Paul B. Hamel and Mary U. Chiltoskey, 1975.

- Hollberg 1763

- Hollberg, Esaias. “Norra Americanska Färge Örter.“ Thesis, University of Åbo, Åbo, Finland, 1763.

- Hough 1914

- Hough, Walter. Culture of the Ancient Pueblos of the Upper Gila River Region, New Mexico and Arizona: Second Museum-Gates Expedition. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 87. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1914.

- Illingworth and Adovasio 2017

- Illingworth, Jeff, and J. M. Adovasio, “Twined and Woven Artifacts: Basketry and Cordage from Huaca Prieta.“ In Where the Land Meets the Sea: Fourteen Millennia of Human History at Huaca Prieta, Peru, edited by Thomas D. Dillehay, 525-56. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017.

- Jakes 1991

- Jakes, Kathryn A. “Physical and Chemical Analysis of Paracas Fibers.“ In Paracas Art and Architecture: Object and Context in South Coastal Peru, edited by Anne Paul, 222-39. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991.

- Jakes, Katon, and Martoglio 1991

- Jakes, Kathryn A., J. E. Katon, and Pamela A. Martoglio. “Identification of Dyes and Characterization of Fibers by Infrared and Visible Microspectroscopy: Application to Paracas Textiles.“ In Archaeometry '90: International Symposium on Archaeometry, 2-6 April 1990, Heidelberg, Germany, edited by Ernst Pernicka and Günther A. Wagner, 305-15. Basel: Birkhäuser, 1991.

- Johnson 1954

- Johnson, Irmgard Weitlaner. “Chiptic Cave Textiles from Chiapas, Mexico.“ Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris 43 (1954): 137-47.

- Johnson 1967

- Johnson, Irmgard Weitlaner. “Textiles.“ In Nonceramic Artifacts, edited by Richard S. MacNeish, Antoinette Nelken-Terner, and Irmgard Weitlaner Johnson. The Prehistory of the Tehuacan Valley 2, gen. ed. Douglas S. Byers (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1967), 189-226.

- Johnson 1977

- Johnson, Irmgard Weitlaner. Los textiles de la cueva de la Candelaria, Coahuila. Coleccion Cientifica Arqueología 51 (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 1977).

- Kasha 1948

- Kasha, Michael. “Appendix: Chemical Notes on the Coloring Matter of Chihuahua Textiles of Pre-Columbian Mexico.“ In Textiles of Pre-Columbian Chihuahua, edited by Lila Morris O’Neale, Contributions to American Anthropology and History 45, 151-57. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1948.

- Kellogg 1912

- Kellogg, Harriette S. “Native Dye-Plants and Tan-Plants of Iowa, with Notes on a Few Other Species.“ Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 19, no. 1 (1912): 113-28.

- Kent 1983

- Kent, Kate Peck. Prehistoric Textiles of the Southwest. School of American Research Southwest Indian Arts Series. Santa Fe and Albuquerque: School of American Research and University of New Mexico Press, 1983.

- King 1974

- King, Mary Elizabeth. “Medio Period Perishable Artifacts: Textiles and Basketry.“ In Casas Grandes: A Fallen Trading Center of the Gran Chichimeca, edited by Charles C. Di Peso, John B. Rinaldo, and Gloria J. Fenner, Amerind Foundation Publication 9. Dragoon, Ariz.: Amerind Foundation, 1974.

- King 1978

- King, Mary Elizabeth. “Analytical Methods and Prehistoric Textiles.” American Antiquity 43, no. 1 (1978): 89-96.

- King 1979

- King, Mary Elizabeth. “The Prehistoric Textile Industry of Mesoamerica.“ In The Junius B. Bird Pre-Columbian Textile Conference, May 19th and 20th, 1973, edited by Ann Pollard Rowe, Elizabeth P. Benson, and Anne-Louise Schaffer, 265-78. Washington, D.C.: Textile Museum & Dumbarton Oaks, 1979.

- King and Gardner 1981

- King, Mary Elizabeth, and Joan S. Gardner. “The Analysis of Textiles from Spiro Mound.“ In The Research Potential of Anthropological Museum Collections, edited by Mary Elizabeth King and Joan S. Gardner, 123-39. New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1981.

- King and Robinson 1987

- King, Robert Merrill, and Harold Ernest Robinson. The Genera of the Eupatorieae (Asteraceae). Monographs in Systematic Botany 22. St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden, 1987.

- Kriss 2018

- Kriss, Dawn, et al. “A Material and Technical Study of Paracas Painted Ceramics.” Antiquity 92, no. 366 (2018): 1492-1510.

- Kuttruff 1988

- Kuttruff, Jenna Tedrick. “Textile Attributes and Production Complexity as Indicators of Caddoan Status Differentiation in the Arkansas Valley and Southern Ozark Regions.“ PhD diss., The Ohio State University, Columbus, 1988.

- Leftwich 1952

- Leftwich, Rodney L. “Arts and Crafts of the Cherokee Today.“ Western Carolina Teacher’s College Bulletin 29, no. 3 (1952): 1-12.

- Mastache de Escobar 1974

- Mastache de Escobar, Alba Guadalupe. “Dos Fragmentos de Tejido Decorados con la Tecnica de Plangi.“ Anales del Instituto Nacional de Antropolgia e Historia 7a, no. 4 (1974): 251-62.

- Michel, McGovern, and Lazar 1992

- Michel, Rudolph H., Patrick E. McGovern, and Joseph Lazar. “Indigoid Dyes in Peruvian and Coptic Textiles of the University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.“ Archeomaterials 6, no. 1 (1992): 69-83.

- Moerman 2022

- Moerman, Daniel E. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland, Ore.: Timber Press, 2022.

- Niemeyer and Agüero 2015

- Niemeyer, Hermann M., and Carolina Agüero. “Dyes Used in Pre-Hispanic Textiles from the Middle and Late Intermediate Periods of San Pedro de Atacama (Northern Chile): New Insights into Patterns of Exchange and Mobility.“ Journal of Archaeological Science 57 (2015): 14-23.

- Ovarlez 2004

- Ovarlez, Sonia. “Comentarios respecto al estudio del azul maya.“ In La pintura mural prehispánica en México, edited by Leticia Staines Cicero, 65-71. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2004.

- Rembert 1979

- Rembert, David H., Jr. “The Indigo of Commerce in Colonial North America.“ Economic Botany 33, no. 2 (1979): 128-34.

- Roquero and Nowik 2006

- Roquero, Ana, and Witold Nowik. “Tintes azules de Mesoamérica: Muicle; un sucedáneo del azul añil.“ In Actas III Jornadas Internacionales sobre Textiles Precolombinos, edited by Victòria Solanilla Demestre, 19-33. Barcelona: Grup d’Estudis Precolombins, Departament d’Art de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2006.

- Sabatini 2020

- Sabatini, Francesca, et al. “Revealing the Organic Dye and Mordant Composition of Paracas Textiles by a Combined Analytical Approach.“ Heritage Science 8, no. 122 (2020): 1-17.

- Sahagún 2023

- Sahagún, Bernardino de. Digital Florentine Codex: An Encyclopedia of 16th-Century Indigenous Mexico, translated by García Garagarza. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2023, https://florentinecodex.getty.edu.

- Sánchez del Río 2021

- Sánchez del Río, M., et al. “Crystal-Chemical and Diffraction Analyses of Maya Blue Suggesting a Different Provenance of the Palygorskite Found in Aztec Pigments.“ Archaeometry 63, no. 4 (2021): 738-52.

- Sibley and Jakes 1994

- Sibley, Lucy R., and Kathryn A. Jakes. “Coloration in Etowah Textiles from Burial No. 57.“ In Archaeometry of Pre-Columbian Sites and Artifacts, edited by David A. Scott and Pieter Meyers, 395-418. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, 1994.

- Splitstoser 2016

- Splitstoser, Jeffrey C., et al. “Early Pre-Hispanic Use of Indigo Blue in Peru.“ Science Advances 2, no. 9 (2016): 1-4, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501623.

- Stern 1970

- Stern, William T. “Ventenat’s ‘Decas Generum Nororum’ (1808).“ In Essays in Biohistory and Other Contributions Presented by Friends and Colleagues to Frans Verdoorn on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday, edited by P. Smit and Rodolphine J. Ch. v. ter Laage, 343-52. Utrecht: International Association of Plant Taxonomy, 1970.

- Teague 1998

- Teague, Lynn S. Textiles in Southwestern Prehistory. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998.

- Torres 1988

- Torres, L. M. “Maya Blue: How the Mayas Could Have Made the Pigment.“ In Materials Issues in Art and Archaeology: Proceedings of the Materials Research Society, 123-28. Pittsburgh: Materials Research Society, 1988.

- Turnbaugh and Turnbaugh 1986

- Turnbaugh, Sarah Peabody, and William A. Turnbaugh. Indian Baskets. West Chester, Penn.: Schiffer Publishing in collaboration with the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1986.

- Van Olphen 1966

- Van Olphen, H. “Maya Blue: A Clay-Organic Pigment?” Science, n.s. 154, no. 3749 (1966): 645-46.

- Wallert and Boytner 1996

- Wallert, Arie, and Ran Boytner. “Dyes from the Tumilaca and Chiribaya Cultures, South Coast of Peru.“ Journal of Archaeological Science 23 (1996): 853-61.

- Webster 1997

- Webster, Laurie Diane. “Effects of European Contact on Textile Production and Exchange in the North American Southwest: A Pueblo Case Study.“ PhD diss., University of Arizona, Tucson, 1997, https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/282534.

- Webster 2000

- Webster, Laurie D. “The Economics of Pueblo Textile Production and Exchange in Colonial New Mexico.“ In Beyond Cloth and Cordage: Archaeological Textile Research in the Americas, ed. Penelope Ballard Drooker and Laurie D. Webster, 179-204. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2000.

- Webster, Hays-Gilpin, and Schaafsma 2006

- Webster, Laurie D., Kelley A. Hays-Gilpin, and Polly Schaafsma. “A New Look at Tie-Dye and the Dot-in-a-Square Motif in the Prehispanic Southwest.“ Kiva 71, no. 3 (2006): 317-48.

- Welters and Ordonez 2004

- Welters, Linda, and Margaret T. Ordonez. “Blue Roots and Fuzzy Dirt: Archaeological Textiles from Native American Burials,“ In Perishable Material Culture in the Northeast, edited by Penelope Ballard Drooker, 185-96. Albany: University of the State of New York, 2004.

- Willoughby 1951

- Willoughby, Charles C. “Textile Fabrics from the Spiro Mound.“ Missouri Archaeologist 14 (1952): 99-109, plates 140-52.

- Wouters and Rosario-Chirinos 1992

- Wouters, Jan, and Noemí Rosario-Chirinos. “Dye Analysis of Pre-Columbian Peruvian Textiles with High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Diode-Array Detection.“ Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 31, no. 2 (1992): 237-55.

- Young 1957

- Young, William J. “Appendix 9: Analysis of Textile Dyes,“ in A Chancay-Style Grave at Zapallan, Peru: An Analysis of Its Textiles, Pottery, and Other Furnishings, edited by S. K. Lothrop and Joy Mahler, Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology 50, no. 1, 33-34. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, 1957.