The indigo dye vat is considered temperamental, beautiful, and complex. Dyers worldwide describe it as “alive,” requiring balanced nourishment to transform insoluble indigo into a usable dye. For some, the vat has a spiritual essence that is cared for and appeased by feeding it ceremonial foods, making offerings, or burying edifices and amulets near the site.

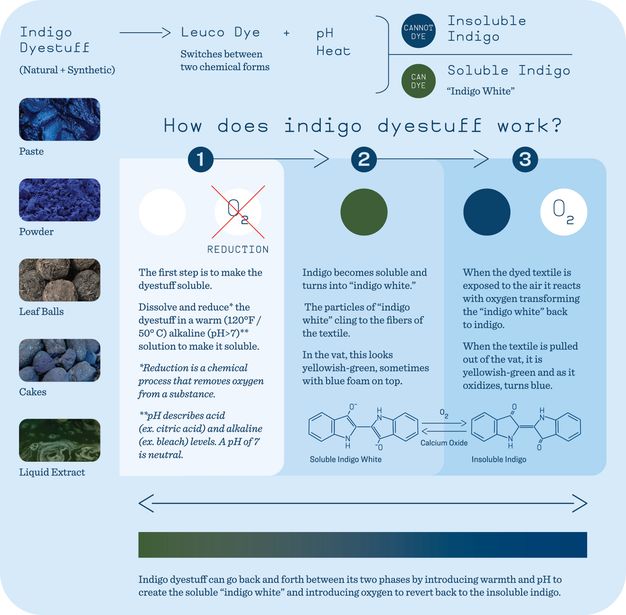

Inside the vat, warmth and alkalinity are introduced, making indigo temporarily soluble. At this stage, liquid is referred to as “indigo white,” which appears yellowish-green. When fabric is dipped into the vat and exposed to air, it turns blue as “indigo white” reverts to indigo. Lighter blues require fewer and shorter immersions, while deep blues need multiple, lengthier dips. During the process, dyers must avoid agitating the vat and introducing oxygen to prevent the dyestuff from becoming insoluble. Dye vats can be maintained and reactivated for years.

Unlike indigo, other natural dyes bond to textiles through high heat and pH levels, and often only with specific fiber sources such as either plant or animal. Indigo is not particular about the type of fiber and instead deposits small colored particles on top of the fibers. The color remains for a long time, as can be seen in early textile fragments; while faded, the blue remains recognizable.

Header Image: Porfirio Gutierrez’s hands in an indigo dye bath, 2024. Photograph by Ron Kerner, 2024.